Plus Ça Change

Owning Shostakovich

By Ben Finane

Dmitry Shostakovich (1906–75) was, and arguably remains, Russia’s greatest composer. He is known first for his great symphonies, the emotional power of which, under the proper baton, are undeniable. Shostakovich’s string quartets are equally powerful and serve as introverted and mesmeric companions to those larger-scale titans. The cutting Cello Concerto No. 1, inspired by Prokofiev’s Symphony-Concertante, feels angry and acerbic — yet retains a dry humor. After Shostakovich’s symphonies, that work shares top honors among his orchestral music with the Violin Concerto No. 1, which splashes in melancholy without drowning in it.

Shostakovich also wrote a fine opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, which the composer labeled a “tragedy–satire.” The work sympathizes with its murderous heroine, Katerina Ismailova, portraying her as a victim of social circumstances. For solo piano, Shostakovich’s wondrous cycle of the cerebral but personal 24 Preludes and Fugues casts the composer in a different color. In addition to these landmark works are symphonic poems, ballet music, incidental music for theater and film, and jazz. All figure into the recommendations below for essential Shostakovich recordings, which seek not to champion certain performances over others but to offer the listener as many angles as possible from which to glimpse the composer’s complex genius.

To say that Shostakovich’s work was produced within the thorny political circumstances of the Soviet Union does not begin to describe the tightrope he was forced to walk throughout his career and life. Political interference and intervention from Stalin’s regime — and from Stalin himself — constantly sought to crush Shostakovich’s music into the mold of socialist realism, an unrelenting dogma glorifying the Communist ideals that began to hold sway as early as 1929. This meddling by the Soviets was made more sinister by its secretive nature, which contradicted their public support and pro–Shostakovich propaganda.

It’s hard not to draw parallels here with present-day Russia’s relationship to artists and artistic suppression, though certainly Vladimir Putin is no Josef Stalin, and his censorship is subtler. “There is the opportunity for artistic expression in Russia right now,” notes Tim Harte, chair of the department of Russian at Bryn Mawr College, “but there have been ways that Putin has kept artists guessing, via selective enforcement of rules and laws about obscenity in art. Essentially, Putin has created a sense that artists better be careful, lest they run into trouble.

“Putin has unified the country, in a way,” Harte continues, “and obviously controls the media so that he has his grip on the taste of the country.” Pussy Riot is a group that provides a fine example of censorship aligning with popular taste: Putin had merely cracked down on a bunch of punks that had desecrated a church in a blasphemous manner.

“In Russia,” says Harte, “you constantly hear ‘You in the West...,’ and that’s something that Putin has played up: Russia diverges from the West in that they have different morals; the West is morally corrupt. Putin offers an interesting mix: he takes a little bit from the Stalinist era, remnants of the Communist regime and remnants of the tsarist, Orthodox regime and creates this whirlwind, leaving artists with the sense that they have to be wary. Further, he employs market forces to regulate how things are expressed through a form of crony capitalism.”

In the West, Shostakovich had to contend with criticism from many in the avant-garde, including Igor Stravinsky and Pierre Boulez, for the conservative (read: accessible) nature of his largely tonal musical language. That language, rooted in the classical tradition but drawing on traditional Russian folk music, popular melodies, and (sometimes) jazz, may indeed seem accessible when compared to the music of thornier twentieth-century composers, but that doesn’t mean it is simple or obvious: Shostakovich often masked his music’s deeper meanings with a bright surface to divert the attention of the authorities and censors. Uncovering this strategy, and speculating as to the extent of its manifestation in the composer’s work, has happily occupied many music scholars since the 1980s, but I’ll leave those depths unplumbed here — except to suggest that much of Shostakovich’s music may also be expressing itself in extramusical ways. In any case, the expressivity of Shostakovich’s language, like those of the great masters before him, is virtually universal; advanced study in modern European history is not required to explore his world.

Symphonies

Any Shostakovich collection should begin with a stellar recording of his Symphony No. 5, which touches on all aspects of the human condition, and Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic provide the best available (Sony Classical). As he did in his great recordings of Mahler and Stravinsky, Bernstein here goes for broke without sinking into schmaltz. The Moderato is frighteningly bold, then creeps away, only to return in triumph. A buoyant Allegretto delights in amusements, then cedes to an intensely heartbreaking Largo that provides the transcendence that every classical listener seeks out again and again. The final Allegro features powerful, blasting brass that push to a raucous, cynical finale. This album also includes Symphony No. 9, a Mozartean neoclassical delight here played crisply and with humor. Woodwinds (especially piccolo) cut crisp lines, while tuba and trombones romp shamelessly.

In a collection distinguished for its raw power, Valery Gergiev leads the Kirov Orchestra impressively through the War Symphonies, Nos. 4–9 (Philips). Though Gergiev lacks a bit of Bernstein’s sensitivity and uncanny, humanistic rubato, his bold Symphony No. 5 is hard to dispute — he and his orchestra are Russian, comrade — and his finale leaves little room to doubt this performance’s unquestionable sense of triumph. Gergiev’s Symphony 9 is scrappy, sloppy and enjoyable. The other highlight of this set is Symphony No. 7, “Leningrad.” Adding the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra to the Kirov, Gergiev puts this work through its emotional paces with satisfying fortissimos around every corner.

Vladimir Jurowski and the Russian National Orchestra deliver crisp renditions of Symphonies 1 and 6 (PentaTone) (SACD) in a sonically superior cycle of the complete symphonies. Symphony No. 1 is given a transparent reading that features delightful piano playing in its second-movement Allegro. The quirky Symphony No. 6 is led in a commendable trot, the highlight being the controlled chaos of its whirling Allegro, followed by a well-measured Presto finale.

Herbert von Karajan’s 1982 recording of Symphony No. 10 with the Berlin Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon) lacks the adrenaline of his earlier recording of the work with this orchestra, but is far more introspective in its approach. Shostakovich described his Tenth as a “portrait of Stalin,” and Karajan’s meditative Moderato is detailed portraiture of considered care and control, making this recording worthy of investigation. The rousing finale doesn’t entirely convince, but perhaps that’s the idea.

String Quartets

In the past few decades, Shostakovich’s String Quartets have made their way into the pantheon that houses the cycles of Beethoven, Schubert and Bartók. Unlike those earlier masters, Shostakovich was not a structural innovator in this genre; instead of pushing out, he looked inward, using form to shape his creativity. Nor did Shostakovich write any “early” quartets, composing his first at the age of thirty-two. In a way, this makes the cycle more satisfying — the listener need not sit through less enticing, early works that gradually evolve into more fluent and masterful ones. The textures of the quartets are often spare, and virtuosity is more functional than empty; the term “bleak landscape,” so often used to describe the works of twentieth-century composers who employed minimal orchestration, applies here in a real and admirable way. Because they achieve passion without pathos, the best recordings of the quartets are those of the Emerson Quartet (Deutsche Grammophon). The group has rarely, if ever, been better recorded, and their and Shostakovich’s personalities seem cosmically aligned.

Two Concertos

The essential recording of Shostakovich’s essential concertos — Violin Concerto No. 1 and Cello Concerto No. 1 — was delivered by the concertos’ dedicatees, violinist David Oistrakh and cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, and remains unsurpassed (Sony Classical). The Violin Concerto is backed by a confident New York Philharmonic, led by an emotional Dimitri Mitropoulos, but it’s the soaring Oistrakh, reaching for the heavens in a wrenching Passacaglia, who is the main attraction. Rostropovich was a student and close friend of Shostakovich, and would go on to become a great conductor and champion of the composer’s work. We hear that commitment here in his impassioned, ruddy performance of Cello Concerto No. 1. In this recording conducted by Eugene Ormandy, the strings of the Philadelphia Orchestra find in the Moderato moments of wonder in which they seem to achieve the tonal quality of the human voice.

24 Preludes & Fugues

Putting aside pedestrian and undeserved comparisons to Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, these gems for solo piano merit attention, regardless of what place they will ultimately find in the canon. The set also triumphs insofar as we hear, in these individualist morceaux, Shostakovich escaping entirely from the grip of socialist realism. Vladimir Ashkenazy performs them with precision, commitment and lightness, even if his pedaling is often heavy (Decca).

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk

Two excellent versions are available of Shostakovich’s great opera of tragic lust. The first and best is the premiere recording, with Galina Vishnevskaya in the title role of Katerina Ismailova (EMI). Her fully rounded portrayal of an unhappy wife married to a rich but impotent man ranges from touching to paranoid to sensual to sadistic. Her lover, Sergey, is the convincingly sorrowful Nicolai Gedda. Mstislav Rostropovich conducts the London Philharmonic Orchestra with fluid, ruthless pacing, and the sound is clear and warm throughout. For those listeners who wish to add visual stimulation to their experience, a video with Nadine Secunde as Katerina and Christopher Ventris as Sergey, in a staged performance at Barcelona’s Gran Teatre del Liceu, will do nicely (EMI). Though Secunde is no Vishnevskaya, she is still compelling, as are the Symphony Orchestra and Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu under the direction of Alexander Anissimov, whose strolling tempos help establish an atmosphere of dread.

The Execution of Stepan Razin

Outside of Shostakovich’s more established repertoire is a work that should earn a place in his canon: The Execution of Stepan Razin, a symphonic poem for baritone, mixed chorus and orchestra. It concerns a seventeenth-century Cossack rebel and folk hero who led an unsuccessful revolt against Tsar Alexis I, father of Peter the Great. The folk-like choral sonorities and gritty orchestral accompaniment invite comparisons to the music of Kodály, Bartók and Stravinsky, but the brooding, tragic undertone makes it clearly Shostakovich. The commendable recording by Gerard Schwarz and Seattle Symphony and Chorale grips the attention, but bass-baritone Charles Robert Austin could use more firepower and a rougher, “folky” edge (Naxos). A driven performance of the symphonic poem October, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the Russian Revolution of 1917, and the superfluous addition of Five Fragments (sketches for Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 4), round out the album.

Jazz, Dance, Film Music

Shostakovich’s “lighter” music is legitimized (to say the least) in three enjoyable collections by Riccardo Chailly: The Jazz Album, The Dance Album and The Film Album (all on the London label). Taken together, they show the strength of Shostakovich’s craft in unexpected genres and orchestrations. The jazz suites employ xylophone, guitar, accordion and saxophone — all instruments exotic to Shostakovich’s usual orchestral palette. The result isn’t really jazz, but the music has a cosmopolitan feel, and Chailly and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra make the most of the jazzy moments, in the process revealing the composer’s humor and wit. The Dance Album features frenetic rhythms in film-music excerpts from The Gadfly and a suite from the ballet The Bolt, performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra. The Film Album is a much darker collection than the other two, with Chailly conducting the Concertgebouw in scores from Soviet propaganda films; a highlight is the flowing Romance from The Gadfly.

Hamlet

Although hearing Shostakovich’s incidental music for director Grigori Kozintsev’s 1963 version of Shakespeare’s Hamlet while viewing the film is ideal, the music alone, with its sparse, dark lines, suffices to conjure up the churning isolation that beleaguers the crown prince. The music for Hamlet’s “To be, or not to be” soliloquy paints a gripping thought process, while Ophelia’s “Descent into Madness” is truly Hitchcockian (and could with little effort accompany any scene from Vertigo). Dmitry Yablonsky and the Russian Philharmonic Orchestra stirringly perform the entire score on a 2003 CD (Naxos). The sound is sharp and detailed, and enhances a piece of theater that is always compelling, even when staged only in the mind.

Of all his film scores, is it any wonder that Shostakovich had the most success accompanying the moody, haunted, enigmatic Dane, who wrestles with serving a villain king while his countrymen suffer? We are fortunate that Shostakovich’s own dealings with a murderer did not end in tragedy, and that his sense of social justice and strength of character prevailed to guide him through darkness, ensuring that his enterprises did not, as Hamlet feared of his own, “lose the name of action.”

More than a century after Shostakovich’s birth, the popularity of his music continues to grow. As the Cold War recedes into memory, let us hope that the politics surrounding his work serve

more to contextualize this great composer than to define him. It seems certain that this shift will take place — any art that withstands the passage of time, as Shostakovich’s seems bent on doing, achieves durability not through the listener’s detailed knowledge of the circumstances of its creation, but through its own universal greatness.

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine -

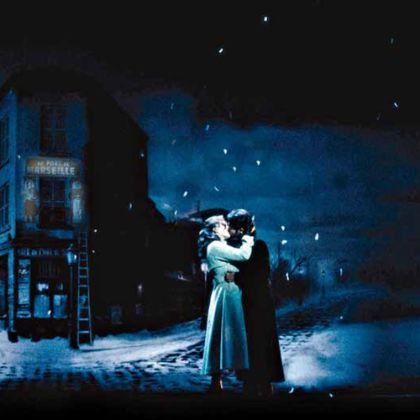

A Simple Love Story

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine