Our intrepid reporter sits through classical-music movies — so you don’t have to.

By Damian Fowler

I don’t know what compelled me to watch the thriller Grand Piano, which was released last year to mixed reviews. Worse still, I failed to heed the letter from the editor in Listen’s spring issue, which warned us to steer clear. But I guess I have to make my own mistakes. Grand Piano is about a “disgraced” concert pianist who attempts to make a comeback after suffering from crippling stage fright. Moments before he is due to perform, he receives a nasty note scrawled in red Sharpie across his music: “Play one wrong note and you die.” Not a bad premise, and enough to set conservatory kids everywhere on edge — the trailer received a lot of OMG–type chatter from young pianists on Facebook — since perfectionism sadly seems to be the name of the game these days.

Elijah Wood, still shaking off the dust of Middle Earth, is suitably bug-eyed as the terrified pianist who arrives at the concert hall moments before the performance. The script, which tries for sassy but is actually pretty tone-deaf, refers to him as a “piano player.” Now there’s a violation already. But let’s not split hairs — the film is so clearly preposterous that to demand realism in its depiction of the concert pianist’s experience would seem churlish. Still, there are some basic things one would hope the filmmakers would have researched. For starters, arriving at the concert hall with minutes to spare, the pianist is given his music by the swaggering maestro. Say what? Okay, I’ve seen Barenboim play the Schoenberg piano concerto with music — complete with anxiety-inducing page flipping every thirty seconds — but are we to believe that a pianist in this state of terror would not have his own copy, or better yet, not have learned his part? Well, yes — when the movie hinges on the note written by a crazed sniper (John Cusack), which requires the pianist to leave the stage, return to his dressing room, pick up an ear piece planted in his backpack so he can communicate with said sniper, come back to the stage after an interminable orchestral tutti, and then indulge in a simultaneous chat-and-play to avoid being shot. Also, what’s with the Bösendorfer being placed behind the orchestra?... I could go on. If I’m being generous about this movie, I would say that it articulates every concert pianist’s worst nightmare, though why the musical unconscious would generate such ersatz classical schlock is clearly a matter for one’s therapist.

Now that I’d watched Grand Piano, I wanted to sniff out other movies about classical music — preferably ones that traduced the noble art, so I could experience the cultural thrill of shaking my head in disbelief. I don’t mean films that use classical music to elevate dramatic moments, such as Disney’s Fantasia, Apocalypse Now, 2001: A Space Odyssey, The King’s Speech, and any number of movies that use “Spring” from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons to let us know we’re in the presence of sophisticated types who shop at Williams-Sonoma. No, I mean movies that focus on a classical figure in the brilliant musician/tormented composer vein. Without a doubt, the best that Hollywood ever produced is Amadeus (1984), which has the advantage of being written by playwright Peter Shaffer. Crucially, the figure of Mozart is presented to us from the perspective of his envious rival, Salieri, whose view of the composer as a child-like goofball is as surprising as it is effective. It helps that the presentation of Mozart’s music is pretty great, too. It’s impossible not to be swept up in Milos Forman’s masterful drama.

You would think that incorporating great music is half the battle, but Hollywood can still mess it up by falling into classical clichés. Figures from the Romantic era in particular have been movie staples for a long time now. And Beethoven especially has long been presented in all his bad-tempered brilliance, a series of tics and tropes standing in for depth of character. Immortal Beloved (1994) comes to mind, which features Gary Oldman as a Beethoven who becomes an increasingly deaf and obstreperous old duffer, although we forgive him when we learn of his heartbreak. And I definitely felt weepy during the climactic scene when the young LVB runs away from his tyrannical dad, the Ninth Symphony driving him on. The same eccentric characteristics crop up in Copying Beethoven (2006), once again with the maestro (played by Ed Harris) presented through another person’s eyes. In this case, that person is Anna (Diane Kruger), a music student at a Vienna conservatory who works as a copyist for Beethoven. Here, the composer is an egomaniacal nutcase, ranting and raving all over town: in other words, he’s a “creative type.”

Another oft-filmed peccadillo of the Romantic–era composer is the tendency to take many different lovers. In 1960, Columbia Pictures released A Song Without End, with Dirk Bogarde as Franz Liszt. (This film was follow-up to the 1945 biopic about Chopin, A Song to Remember). Of course, when Liszt meets Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein (played by the French model–actress Capucine in her debut), he falls head over heels, and immediately makes plans to leave his long-suffering lover — a domesticated countess — at home with the dirty dishes and the kids. But the lothario Liszt is redeemed because, well, he’s a damn good pianist, a “creative type” whose trajectory allows him to bed whomever he pleases so long as it’s passionate. “Franz never fails to notice a pretty woman in his audience,” cautions the countess. While neither the Chopin nor the Liszt films are defensible as history, there’s considerable pleasure in watching the Romantic era refracted through the post-war Hollywood studio system. It’s kitsch fun, with lines like “Gee, Liszt, that sounds great!” And yet to their credit, both movies give plenty of screen time to the music. A Song Without End features over forty musical selections, according to the liner notes of the soundtrack, which were played by the pianist Jorge Bolet. Furthermore, they were recorded before filming began so Bogarde could learn the finger movements necessary to give the illusion of hitting the right notes — though how he managed to handle the Hungarian Rhapsody only God, or Charles Vidor, knows.

Post-war Hollywood also made some great noirish films centered on a musical figure. I reveled in the classic(al) horror of The Beast with Five Fingers (1946), in which a murdered pianist’s hand keeps returning to play Bach’s Chaconne on the piano. Peter Lorre is excellent as the pianist’s personal secretary and steals the show with his strange, creepy behavior. Deception, also made in ’46, stars Bette Davis as Christine Radcliffe, a pianist and music teacher who is reunited with a cello-playing lover she believes to have died in the war. Their rekindled passion spells trouble because Christine has a sugar daddy, a temperamental composer–conductor by name of Alexander Hollenius (played by Claude Rains), who is not averse to a bit of musical revenge. It’s hammy, flamboyant melodrama, but I loved it. What’s more, the original music and Hollenius concerto were written by Korngold — another good reason to skip Grand Piano and watch this one.

Modern-day filmmaking tends to view the piano, and indeed any musical instrument, as a means to redemption. It’s especially fond of artists with psychological issues: music and madness, a match made in Hollywood. I’m thinking of Shine (1996), with Geoffrey Rush playing David Helfgott, driven to breakdown, only to return in glory to play the Rachmaninoff Third. Another movie in a similar vein, The Soloist (2009), stars Jamie Foxx as a down-and-out cello prodigy with schizophrenia. Maybe I’m a piano snob, but this is a film I’ve resisted watching partly because I can’t accept that a cello played by Jamie Foxx can redeem anyone. Also, this film is writ large with dollops of Hollywood self-righteousness, unlike some of those older classics. For cello fans, I’m sure Hilary and Jackie (1998, about the du Pré sisters) is a better bet.

And finally, for people who’ve long wanted the oboe to have a starring role, there’s a glimmer of good news. This year, Amazon Studios announced plans for a new series, Mozart in the Jungle, based on the 2005 memoir by Blair Tindall, a professional oboist who shatters the image of the classical artist with revelations about sex, drugs, and good embouchure. For example, I learned that classical musicians like to drink and sleep around. Who knew? After discovering the pilot online, I was excited at the prospect for all the wrong reasons. Surely, this would be perfectly awful. The trailer gave a preview, with Gael García Bernal as Rodrigo, who seemed to be a lightly fictionalized version of Gustavo Dudamel: “A man who need only be introduced by his first name!” To my surprise, I found I enjoyed the whole thing. I’d anticipated that the show would portray classical music with that familiar fawning respect that preserves it in aspic. But no, it had a lightness of touch, an amusing script, and some surprising insights into the sexual preferences of percussionists. Also, there was Malcolm McDowell as an aging maestro bristling with resentment towards his younger, preening, more brilliant successor. Even Joshua Bell makes a cameo appearance playing Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto. What sets this show apart is that this time the musicians were in on the joke.

related...

-

Sound and Vision

A top twenty-five of Bowie beyond the hits

By Bradley Bambarger

Read More -

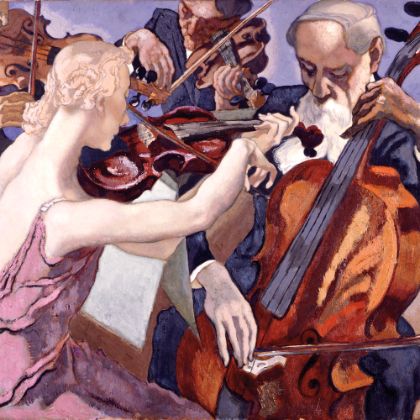

Snapshots in Time

A cellist shares his favorite recordings — and one of his own.

Read More

By Eric Jacobsen -

First Love

Our readers share the moment they were first ensnared.

Read More