American cellist Zuill Bailey preaches the gospel of life with classical music.

By Ben Finane

Zuill Bailey’s first name is pronounced “Zool,” a classic last-name-first Scotch–Irish American–Southern tradition; Zuill is also his father’s name. Bailey’s 2010 recording of the Bach Cello Suites (Telarc) sat at the top of the classical charts for two years, thanks not just to the quality of the recording but to a lifetime spent in audience building, as Bailey details below. The cellist is artistic director of both El Paso Pro Musica in Texas and the Sitka Summer Music Festival and Series in Alaska; and he is professor of cello at the University of Texas at El Paso. Bailey, speaking to Listen at New York City’s Steinway Hall, knows what he wants to say, and doesn’t need me to prompt him with a question.

The cello repertoire is interesting. Cellists are a different breed. The repertoire pushes a sort of community involvement. There are lots of cellists that are conductors and artistic directors and organizers. There are cello festivals. You don’t see violin festivals.

And yet the cello repertoire seems more limited.

And yet we have this shining example by every composer, excluding maybe Mozart. But one of the greatest works Dvořák wrote was the Cello Concerto — and arguably the best concerto [period] is the Elgar Concerto. At some of the musical high points in a composer’s life, we have the five Beethoven sonatas, the Brahms — early and late period. The cello is such an involving instrument, and so vocal, especially as the technique has developed and developed. Any great composer can be transcribed — say the Franck Sonata — and it works perfectly well on the cello.

Your Bach Suites reached number-one and they stayed on the charts for quite a while.

They stayed on the charts for about as long as I think they are able to stay on the charts: I think you can be on the charts for two years, and then, given the shelf life, they have to move on. They’re still chuggin’ away and I’m actually astounded by that. Personally, I collected about a hundred different versions of the Bach Suites on recording. Every cellist that is able to tries to tackle this mountain.

I don’t think you get a Bach Cello Suites record on the charts for so long by recording the album and sitting on your ass. I’ve seen you do local outreach, going on morning television and saying ‘My name is Zuill. This is a cello. This is Bach.’ Really from the ground up. There’s a lot of extramusical effort here.

Well maybe I should tell you how that all began. I was raised in a perfect storm, in the Washington, D.C.–northern Virginia area —

— in Rostropovich’s backyard.

Right! But my parents are musicians, my sister’s a violinist. Between my house and Washington, D.C., there were at least ten regional orchestras that all had major seasons and soloists of note. My school had people come to play. The arts and culture were such an obvious part of my childhood. I never thought that was abnormal. It changed me: it made me feel; it made me expressive. I was in the National Symphony’s Fellowship Program, which paid for your lessons with a member of the symphony. I had accessibility to Pinchas Zukerman, Rostropovich, Janos Starker. We would hear them play, play for them, ask them questions. I was given opportunities to grow — not just as an individual but as a member of a community, something bigger than me.

During my debut at thirteen, someone came up to me backstage and said ‘I want to give you some advice: if you can find what you love to do — and find a way to make that your life — then you will never work.’ And I thought about it for ten seconds and thought: ‘The cello, music, this is it.’

From fifteen to twenty-three, I did lots of compositions and I was playing thirty recitals a year as a college freshman in all these small towns. These towns didn’t have programs, so I would announce works from the stage and I got comfortable communicating. At twenty-four I had built up this existence that had me traveling around and realized I needed a manager. A lot of younger musicians think that a manager is going to get them that trophy; they don’t realize that they need to get the trophy first —

They have to be overwhelmed to the point where they need a manager to manage and organize what they’ve already built.

That’s right, and I got the manager I’m still with now. I had built up recurring gigs because every opportunity I had to perform, I was usually invited back. I would become part of the community: in addition to the recital, I would go on TV shows, go to the local libraries, the schools. It’s not PR: it’s spreading the word.

I started realizing there was this big void, because everywhere I went, I would invest myself in this community, and once I left, there was nothing there. And it hurt me to see kids I had seen three years ago say ‘It was so great to meet you and I think I’m going to go into music but I’m not sure because there’s nothing else going on here.’

At twenty-eight, I was asked to be the director of El Paso Pro Musica, to sculpt the cultural landscape of the region. I knew I wanted to do this and moved in 2001 from Manhattan to El Paso, Texas, to be hands-on, behind-the-scenes, to make it happen.

What is ‘it’? The classical music gospel? An infusion, an awareness? Bringing music where there was no music before?

Consistency, awareness, an understanding.... By understanding, I mean I want people to know why they feel the way they feel, not to think that it’s ‘normal.’ Because once you lose these kinds of things you can’t get them back. If they realized that this feeling is oxygen for the soul, as I think it is, then it’s addictive: you have to have it; you need it for nourishment. Whether it’s buying a classical CD, seeing a piece of art or understanding that the opera is also about the spectacle of costumes, the singing, and being there with the community to celebrate the arts. We work together — the symphony, the opera, the [El Paso Museum of Art]. In the museum collaboration, we see that the visuals of the time were the same as what people were hearing in music. Our “Bach’s Lunch” noontime events at the museum provide thematically charged concerts, enabling you to walk around and see and hear. I started videoconferencing — outreach pushed out to forty schools. I started something called “Bach on Demand” where I went to the cable station and did three or four outreach-y things: when the school has a substitute teacher, the substitute can push a button and have me in the classroom teaching students about the cello. So twelve years later now we’re a healthy not-for-profit that’s a shining example of looking at the long-term horizon, not the short-term spike. So kids that were in the third grade are now in college — and they’re coming back to El Paso because that’s their treasure, their safe place, their arts and culture.

So everywhere I get invited to play my cello, I ask ‘How can I help you?’ and this brings us back to the success of the Bach recording. I’ve tried to show musicians that it’s their responsibility not to do something to get PR but to do something for the betterment of any community because that’s the reason they have a gig. The reason we all have platforms is because people appreciate it. Most people now are looking for a PR move, but life is about the process, the long-term, something bigger than us.

I was asked to do the same thing in Alaska as I did in El Paso. This worked out because the El Paso festival is in January and the Alaska festival is in the summer. Alaska is the most gorgeous place on earth. The Sitka Summer Music Festival is in June and throughout the year it tours the state.

Do you find similar reactions in these two enormous, polar-opposite American states?

People trust me because I’m not trying to sell them something and leave town.

— like The Music Man —

I’m breaking bread with them, living the life. I’m the consistent lightning rod that shows: ‘This way.’ In the Telarc years, the Bach Cello Suites, I sold record numbers of CDs at concerts because after the show listeners didn’t want to let go, they wanted to take something with them.

And those who don’t live in New York City, Chicago or LA may not have an orchestra within traveling distance, so recordings are the best way to access classical music.

And they’re tangible. I love the physicality of the CD — the album, whatever people use — versus the Cloud. You can hold it; you can read. There’s an act of just being a part of it.

So this is how a career, an environment, a planet of thought is built. I have a multi-tiered, multifaceted environment that I live in, that has to do with the greater good, not numbers. I have to travel less by being in these places. I’m now director of the Northwest Folk Festival, having just succeeded Gunther Schuller. And I teach at a university. Same exact reason: it’s building a better world. It’s a unique existence that feeds itself. I don’t get tired of it. I don’t want to make a career built on playing the Dvořák Concerto every night. I want it to be fresh. I play about eighteen different concertos, and when I sit down in front of an orchestra to play, I get this big smile on my face, because I’m thinking: “This cello, this is the key that made all of this possible.” It gave me the passion to jet out — outside of the cello — and try to make a difference. Because none of these other things I’ve just mentioned have anything to do with the cello.

When you perform a transcription — something not written explicitly for cello — are there challenges that come with that?

Yes, my biggest thing with transcriptions are that they have to sound like that’s the way they go. They can’t sound as though I’m playing in falsetto. In other words, if the violin piece is high in the violin’s register, I’m not going to play it up high in the cello because it doesn’t sound right. Hearing someone’s voice on helium, it doesn’t sound right. To me, it’s as basic as: that register doesn’t make me comfortable. Then you have to ask, ‘Is that the point?’

‘Is comfort the point?’

When the composer wrote it, was the ascent to the higher register on the violin supposed to add tension to the musical line? If that’s the case, then you leave it there, because that’s justified. For the most part, you can bring it down an octave or a fifth below or change the key to make it lock in.

Do the Bach Suites remain the summit of cello literature — despite the fact that they came. . . first?

The difficulty with the Bach Cello Suites is that we don’t have the manuscript. Not only is it the most perfect writing, but it’s open for discussion because we don’t have the word of Bach setting us straight — so it’s flexible as to where you are at any particular moment.

The performer has more decisions to make —

Right, so when I decided to tackle this project, over ten years ago, I decided — and this is my motto in life — that you have to know where you’ve been to know where you’re going. You can’t just feel it and think you’re right, because feeling it doesn’t mean you’re an educated person.

I find that Bach in many ways is kind of the ultimate Romantic. This music, it touches your soul in a religious kind of way.

‘To know where you’ve been,’ does that mean revisiting the past?

It means going back to the early manuscript of every possible thing that people have said around Bach’s lifetime, then you go a generation later, and later, and you keep building it. Then you understand, in the nineteen hundreds, where these people got their ideas from. So it’s not the grapevine effect, where you heard the way someone played it and then just copy what they do — but badly. You go back and revisit the source: so I did. I went back and essentially learned what I deem as being the closest thing we have to Bach — which is Anna Magdalena, his second wife — and I studied the manuscript religiously.... It’s funny, I learned the Suites again as they were perceived for two centuries, as etudes or warm-up exercises. I went back to make sure the rhythms and the notes were sterling: I didn’t want to get myself in the way yet. Once the structure and the rhythms were established — the rhythms change in some of these editions — and once the notes were established, because these too are negotiable, I then added the phrase markings that Anna Magdalena put in. Then I studied the scholars who studied her and what they came up with, and I made decisions based on that. Once that was all established, I put it all away for two years without ever looking at it to see where I evolved, and that’s where my interpretation for the recording was spawned. So I knew at any given moment, if someone asked, ‘Why do you do it this way?’ I could say, ‘It’s because of this, it’s because of that.’

And that final product certainly has a lot of rubato. When you use rubato in this way, how do you balance it with the larger structure?

I think it goes back to the Elgar Concerto. When I recorded it, I had always yearned for... not a clean approach, but an elegant, pristine, English–passionate approach versus what we’re used to, which is ‘I feel every moment like it’s my last moment.’

So an ‘English’ approach, is that less drama, a quieter drama?

Yes, and more elegance, a kind of sophistication. Again, this was purging everything I knew from recordings and performances of the Elgar and going back to the basics of the piece. I literally found Elgar’s score and followed his markings verbatim, then let it go and tried to get out of the way of the music, versus feeling the moments because I felt them.

One of the things that made Rostropovich the historic performer that he was, was that he always looked at the horizon: his musical lines were ridiculously long; they weren’t momentary or miniaturized.

There was a through line.

Through the whole thing. My feeling with the Elgar is that you have to understand that a moment is part of a bigger picture, not a moment that stops time. Because time doesn’t stop.

You’ve gotta keep it going!

That moment can be felt, but the momentum keeps going. What was fascinating, once I put this all together and applied it to performances of the Elgar, was that my rendition was minutes faster than others. Yet I did nothing other than exactly what the composer wanted. I felt it, too, but I wouldn’t let myself sob openly on any given note that would stop the phrase. I might tear up, symbolically, but I wouldn’t stop everyone from playing so I could bawl and then try to get back to the music.

So in Bach, it’s the same thing. I find that Bach in many ways is kind of the ultimate Romantic. This music, it touches your soul in a religious kind of way — in a this-is-bigger-than-all-of-us way — but yet you have to look at the long line. And when you change or do rubato, you have to understand the structure. You can pull apart a chord, but the chord still leads someplace. Is it the top of the chord? Is it the bottom of the chord? You have to go through. Rubatos, I try to make them elegant, not obtrusive.

And that’s where I am right now, musically. I’m trying to use all the tools that I have worked to refine to not get in the way of the music and make it about me, but to make it about the music. And make these people want to hear this music over and over again, and I think that’s one thing that the Elgar recording enables the listener to do. You can listen to it over and over again: it’s not so wrenching that you have to put it on the shelf and take a break from it.

It’s not Mahler Five.

No, it’s not heavy. The Bach was different, though. My cello brings out things that other cellos don’t.

It’s a richer, darker sound than maybe I’ve ever heard from a cello.

Yes, it was essentially a church bass back in 1693.

It could certainly double as a double bass.

That’s why Alexander Schneider of the Budapest Quartet used it: it creates an environment of sound.

I saw a clip of you giving a masterclass on the opening of the Elgar Concerto. It was great, because you convinced this student that OK, even though it says quasi improvisando, let’s go back. You haven’t earned that yet. You’re sort of playing it the way Rostropovich played it, but there was a process he went through. And, like in theater, you learn the script and learn the script — and then you put it down. And then you can take your dramatic pauses because you know your lines, you know everybody else’s lines —

And the dramatic pauses are natural; you know and feel them in the bigger picture.

When I think of American cellists, I think of an elegance and boldness; it’s full-bodied.

I know you’re a great collector of recordings. Is there a continuum that all these recordings give us that ultimately reveals an evolving interpretation across artists for a particular concerto? Or is it an individual decision that each individual artist makes after knowing the score cold? Is it important to build off of what Cassals and Rostropovich and every one else has given us or —

It’s a very smart question. The difference today in musicians, for the most part, is that as a world we are all intertwined now. We understand — because we can get on the internet and have recordings all over the place — what are other people are doing. Back when… you mentioned Cassals or even early Rostropovich: this was a Spanish player; this was a Russian player. Gendron was a Frenchman. Fournier, Piaitigorsky, Feuermann, Leonard Rose. You’re talking about flavors. As we have evolved our flavors have become more neutral, because people are trying to be liked by everyone. Back in the day — meaning when you stayed in the country because you didn’t travel much — you would hear the great Russian blank-and-blank and it would sound so different. When Rostropovich came over here in the fifties and played his crazy debuts, no one had ever experienced that before. They were used to the guy in the suit sitting very elegantly at Carnegie Hall and playing very elegantly for three hundred to five hundred people. Rostropovich came and lit the place on fire with passion and playing to the back of the hall in a way that no one had ever seen. That opened the door for grandeur and larger-than-life.

Perspective is everything. I love knowing what I just told you. I love that when you listen to the recording of those concerts, it’s not very refined. It’s heavy-handed and for live performance. But you go back and you listen to those guys in the suit — a Pierre Fournier, Leonard Rose, János Starker — you’re hearing some of the most refined playing, in concert. It’s a different animal.

One tactic for performance, one for recording.

That’s right. Or both: ‘I want to play refined because I want this beautifully tailored suit. I’m not looking for the flashiest colors that will be seen when I play in Giants Stadium.’ I used to be able to turn the radio on and tell who was who because I knew their flavor, their cello sounds. That’s Cassals. That’s Rostropovich with von Karajan. That’s du Pré. These sounds were unique. And I think the use of steel strings back then with gut — steel on gut — you had to create a sound. Now you don’t. The sound is made — boom! I don’t think a lot of musicians go far back in history enough to know why those guys sounded the way they sound.

What schools they were with.

Schools, culture, what was expected during the time. You have to know much more than ‘I like it’ or ‘I don’t like it.’ When you’re hearing Cassals, you’re hearing him at forty years plus — because he was born in the eighteen hundreds! He was a baked, formed artist at this point.

We don’t get the evolution we’re able to hear with other artists.

I wish he had been born a little later so the recordings were of better quality! He also had no examples. His Bach Cello Suites — no one had recorded Bach before him.

He’s flying blind.

He’s like the 3M commercial: ‘We don’t make it, we make it better.’ He’s making it and making it better. He created it. Feuermann died at thirty-nine. I’m forty-one. Everything we have of him…. du Pré stopped and couldn’t play anymore after twenty-seven. [Jacqueline du Pré’s career — and life — was cut short by multiple sclerosis.] Twenty-seven! You go back and think of what she did at seventeen — it’s astonishing! Astonishing not only that she made those recordings but that we were able to capture it before that happened. In the case of Rostropovich, I have nine recordings of him doing Dvořák, and they evolve from Dvořák played by Rostropovich to Rostropovich playing Dvorák.

You’re saying how the flavors are becoming more neutral. Do you consider yourself an American cellist? When you play American composers do you bring an Americanness to that?

I don’t know how to answer that question. When I think of American cellists, I think of Leonard Rose. He was the first cellist of America — which is to say U.S.–born. When I think of American cellists, I think of an elegance and boldness; it’s full-bodied. I definitely play as I am. I want to tell my own story with my words, my excitement, with empathy, awareness and sensitivity. That’s how I project music, too. I want you to know what I know and believe as much as I do. I appreciate education, depth, quality, refinement, dedication, respect — and those words are used because that’s what I try to do in the music. When I’m playing, I want it to be about something bigger than me. And I want it to sound like me. I would like, in a perfect world, for a young cellist to turn the radio on, hear me play, and know it’s me… and to say ‘I know that sound. I trust that sound. And I want to learn more about this music.’

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine -

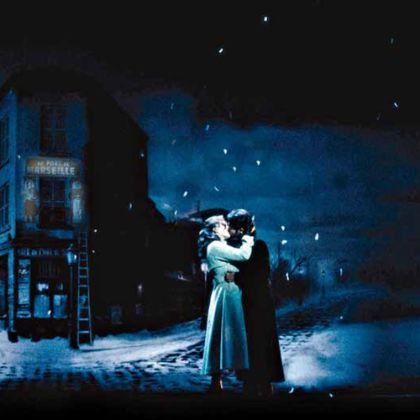

A Simple Love Story

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine