Russian Russian

Maestro and impresario Valery Gergiev discusses the legacy of Prokofiev and Stravinsky along with his opera-house arms race

By Ben Finane

Illustration by Demetrios Psillos

Valery Gergiev is principal conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra, artistic director of St. Petersburg’s White Nights Festival and former principal guest conductor of the Metropolitan Opera. But the Russian’s heart lies in the Mariinsky Theatre, where he has been the artistic director of the opera company since 1988 and general and artistic director since 1996. Maestro Gergiev spoke to Listen in the conductor’s room at Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall. His answers more James Joyce than Leo Tolstoy (with all roads leading back to Saint Petersburg), the maestro illustrated them with the rather Russian mannerisms of leaning forward, brow furrowed, hand tragically on forehead, rubbing the temples or, alternately, the mouth. Fortunately, advanced digital technology enabled the capture of even the most muffled mumble.

What do you hope to record on the new Mariinsky label?

Well, let’s put it straight: Russian music in the first place and we are definitely in a position to record operas. To be honest, we already recorded two, The Nose of Shostakovich and Enchanted Wanderer of Rodion Shchedrin, a great Russian living composer. For me it does not matter if a piece I conduct was written fifty years ago or five years ago or five days ago, it is important for me that the Mariinsky throughout its history always had a very serious focus on operas, on ballet scores of great Russian composers, one by one. It was all-important for the Mariinsky not only to perform music of Verdi, but to work with composers like Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and with very young, brilliant musicians like Stravinsky, Prokofiev and then later Shostakovich. It is still important now. I will work not only with Rodion Shchedrin but with younger composers, a lot of living composers. That’s my hope. Of course, that’s not to neglect Shostakovich, Rachmaninoff, Wagner operas.

What does it mean for you to champion Russian composers?

I believe we know how to perform music of Russian composers. The orchestra, chorus and voices trained in the Mariinsky practically breathe the air of this tradition all the time. Being part of the Mariinsky family, it means you immediately start to learn, and then more, and then even more about this tradition, working with those who are now in their fifties, maybe their eighties. And no one wants them to leave because they are part of this glorious tradition. We do not regularly import voices from Europe and America.

What repertoire are you drawn to outside the Russian repertoire?

Wagner’s Parsifal, and later we will do the Ring cycle.

So this week you’re conducting a Prokofiev symphony cycle at Lincoln Center. Tell me what place Prokofiev holds for you in the Russian pantheon.

A very important composer in my life. Prokofiev became one of the Mariinsky’s — you maybe don’t speak like this in the musical world — flagships in our repertory, which includes sixty or seventy operas. But Prokofiev became all-important for me when I conducted my first opera at the Mariinsky, thirty-one years ago as a student. I conducted War and Peace. So it was my destiny maybe to always either do nothing or do something very big — in this case, it was War and Peace. After that, I spent much time learning about Prokofiev. His symphonies are only a small — though important — part of his great legacy that interested me. When I am interested, this is normally translated into action; at the Mariinsky, there are fortunately unlimited resources for mounting any opera or ballet by Prokofiev. Never has there been an opera company, ballet company, theater so dedicated in promoting the music of any other major composer of the twentieth century. Prokofiev is well served by the Mariinsky and now it is a great pleasure for me to come with the London Symphony Orchestra and perform the Prokofiev symphonies.

What is the driving impetus behind the White Nights Festival?

As artistic director of the White Nights Festival, I can say that we equally engage our forces in performing opera and ballet — music which is theatrical — but also a huge concert program, which includes chamber music, symphonic music and oratorios, because we built a new hall, a very important achievement because this hall is actually a venue where we make our recordings. It’s a Stradivarius; it’s a fantastic hall acoustically. [St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theatre was destroyed by fire in 2003 and was rebuilt in 2005, with Gergiev engaging architect Xavier Fabre along with Yasuhisa Toyota, an acoustician responsible for Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles. —Ed.]

How has the life of a Russian musician changed in the past twenty, thirty years?

Many, many Russian musicians and singers are traveling around the world. But what I’m interested in myself is to work with Russians who are not only Russian by name or birth, but those Russians who are of course gifted, brilliant artists, who also really belong to this tradition, and who do not try to artificially break with the tradition and who understand and respect the fact that in their genes they have all the vitamins, the right elements, all the juices of what we think is a very good tradition, important for the world. Of course, great Italian opera maybe is unbeatable. The great Austrian and German symphonies. Of course there is a lot of good music written by French masters. But all in all, in a summary, Russian composers were so successful, first in simply catching up with Europe: in the middle of the nineteenth century, they already looked promising; at the end of the nineteenth century, they looked extremely powerful; by the end of the twentieth century, you have a very difficult situation if you want to, say, announce which music is performed more often or which tradition dominates. If you take the number of Nutcrackers or Swan Lakes, then of course you have Mozart and Puccini....

How can you tell which Russians belong to this tradition? How can you separate these Russians from other Russians?

Vengerov or Kissin, for example, when they play violin it is unmistakably Russian School and unmistakably going back to the golden age of Russian tradition. But it’s very difficult to separate even American School from the Russian School of violin — Auer, Mischa Elman, Heifitz, Piatigorsky.... But again, I’m not here to tell you Russians are more successful than others, I’m saying the rise of this tradition is a tremendous, unique crescendo. In the beginning it was a small group. Then, of course, you saw Stravinsky becoming a very international figure.

Do you feel that Stravinsky’s musical language has at last settled in our ears?

I think Stravinsky gave us maybe ten masterpieces that millions of people enjoy regularly. And of course, three Russian ballets — though I always say four. Firebird, Petrouchka, Sacre, some people think that’s it, but I would say also Les Noces is fantastic, which we want to record for sure and I think we know how to perform it.

There aren’t enough recordings of Les Noces.

No, no. I made a recording in Holland, but it was basically a radio recording of a live concert and was not released worldwide. I will certainly do it very soon. It is terribly important for me to perform music of Stravinsky because I find myself more and more a conductor of the Russian School. My upbringing, my music training is totally Russian. At the same time, everything I remember from my first three or four years is playing Bach or Beethoven on the piano. None of my teachers told me to start with Rachmaninoff or Prokofiev. The same with symphonic music: when I had played the Beethoven sonatas as a pianist, my first teacher wanted to go through how sonatas are written, and from sonatas we moved to the symphonies of Beethoven, just to understand the structure, the form. It was again Beethoven and Beethoven and Beethoven. And some Mozart and Haydn.

Do you want to change that?

It’s the right way to learn about music. For a historical background in classical music development, you don’t go back five hundred, seven hundred years — it’s enough to start with Bach and then see how the classical language became more and more various and intensive. Germany and Austria and Italy and then France and then Russia. But today Russia is a giant amongst maybe three giants, maybe four giants.... But again, to make recordings in Saint Petersburg, it’s not only a great pleasure and opportunity but also a great responsibility. As you mentioned, there are not enough recordings of Les Noces. I think it’s my responsibility to record Shchedrin, and, if all goes well, of course we should record Les Noces, because there is not one recording that is Russian Russian. In recording Les Noces — the chorus part is all-important, as you know — our choristers all think in Russian. As Stravinsky said of himself: ‘I am Russian. My tone is still Russian. I think in Russian. I feel in Russian.’ His pulse was Russian.

Which of your musical accomplishments are you most proud of?

I am not a man who always thinks of his own achievements. I go on working and traveling, sometimes a lot. I think through our difficult years, the Mariinsky was growing, not only in size. We are building now another opera house, because we believe it will be one of the most beautiful — certainly most powerful technically and hopefully artistically — new opera houses of our time. We continue to look at what else one can do with a new opera house: beautiful for audiences, great for artists, good for composers, strong education — let’s call it enlightenment — you bring in a lot of young people. When you build something new, people are interested. The Mariinsky continues to grow to become one of the most powerful cultural conglomerates in the world. When I say ‘powerful’ I am not trying to match what Hollywood does, but easily we can match whatever is done by other great theaters — Vienna, La Scala, Paris, The Metropolitan Opera. This is clearly not only my goal, my task, but also clearly absolutely achievable. It’s very interesting to see what the Met is doing with these broadcasts to cinemas. We also have all the equipment needed to do the same. We televise several gala, ballet, concert and opera evenings. To simply televise War and Peace is a huge task; obviously we have to do it.

Basically my best achievement is altogether twenty years of enriching the repertoire of the Mariinsky and becoming more and more confident, not only as a leader and artistic director but simply a more confident artistic family. I don’t want to risk saying it here, but…it looks unshakable, that we are so rich in resources. I think it’s destined to continue and do big and important things. There were seventy performances in St. Petersburg only in January, half of them for people who can’t buy expensive tickets: operas, some ballet performances — of course Nutcrackers, but also Magic Flute. But it’s amazing to consider the fact that Magic Flute was performed sixty times in one season. Six zero. And I’m not pushing, saying, ‘Oh, we have to set a world record! Let’s push for a hundred performances of one opera!’ It’s not a musical. We perform forty operas every given season — on stage, not in concert. But the demand was there — families, schools, grandmothers, grandfathers. This is the big social power. Not social like party and champagne and caviar, but social importance because society — the community — respects the Theater as a cultural institution.... When I was a child it was important for my mother, now it is important for me — what my children will hear, what they will see. Instead of watching some really terrible movies, where people go in and kill each other for two hours, I much prefer my daughter or my sons to see another Nutcracker.

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine -

A Simple Love Story

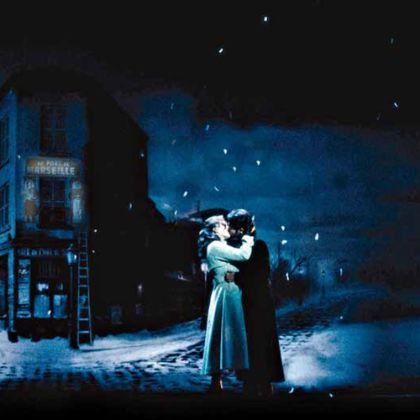

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine