A Rock Star in Winter

Embracing his inner baritone and lutenist, Sting goes classical.

By Ben Finane

Photographs by Tony Molina

The last few years have seen undisputed rock god Sting turning in a widening gyre away from rock, jazz and world-music idioms toward the less familiar airspace of classical music. The singer–bassist took up the lute in 2005 and the following year released a collection of works by Elizabethan composer John Dowland, Songs from the Labyrinth (Deutsche Grammophon). This year saw the release of Twin Spirits (DVD, Opus Arte), a theatrical production about the relationship between Clara and Robert Schumann. Sting and his wife, Trudie Styler, portrayed Robert and Clara in words and were backed by the singing of Simon Keenlyside and Rebecca Evans, who performed songs and Lieder by both Schumanns. Sting spoke to Listen at a New York recording studio, where he was putting the finishing touches on his new winter album, If On a Winter’s Night (Deutsche Grammophon).

Looking over your musical path — from jazz fusion to rock to world music, from three- and four-minute pop songs to longer-form pieces, from 4/4 to more complex time signatures and mixed meter — does your burgeoning interest in classical music come as part of a natural evolution in your search for greater musical complexity?

I’ve always been interested in classical music and was exposed to a lot of it as a child. I don’t really view classical music as a monolithic structure that is impregnable. And there are more ways into it than through the conservatory, as much as I respect that route and that discipline. I treat it with respect, but I feel there are things that I can tackle and make my own, or at least put a different spin on it. I mean, I’m not competing with Plácido [laughs], I’m being myself when I tackle these songs. I’m not a classically trained singer at all, by any means. But, as you well know — with as much respect as I have for that form, it’s a very artificial way of making sound, employed to fill a concert hall without amplification. Now that we have amplification, I think music stylistically tends to follow technology, whether it’s the piano or whatever: you can argue that you can’t play Bach on a pianoforte if you want, but that takes a huge amount of beautiful music out of the canon. So I think sometimes you can afford to innovate, even allowing a parvenu like myself into the fortress just to see what happens.

In Songs from the Labyrinth, your vocal sound begins to differ from that of your earlier solo work. More of an emphasis is placed on longer vowels, legato phrasing, hairpin crescendos and I would even venture to say that you are using more air. Can you discuss your approach and the thought process behind it?

I suppose that material itself would dictate a few stylistic changes. Just the way you need to sing a diphthong is different than the way you’d do it if you were singing a blues or singing rock ‘n’ roll. And so I had to compromise to a certain extent. I had some help there from an American chap, Richard Levitt, and he said, ‘Look, I like the way you’re singing, but take a breath there and don’t take a breath there.’ It was very simple help, but it was very useful help. And I’ve felt that Dowland songs were written before bel canto was invented, when they would sit in small rooms around tables and sing. I can’t imagine that they’d be belting it out like Luciano. So there’s an argument that that’s the way they were designed to be sung. There’s no way you can prove it either for or against [laughs], and I have a great deal of respect for the way it’s normally done by tenors and countertenors — beautiful, amazing technique, but it’s not me. And so I wanted to do something... that was me.

You’re still playing the lute. Tell me about the challenges and rewards of taking up an instrument like that… you started it a couple years ago?

I started it four years ago. It’s a bitch. It’s a very, very difficult mistress: too many strings, tuning is a nightmare, and nonetheless I’m fascinated by it. It’s almost a symphonic instrument; it has this huge range. I’m enjoying that — it’s probably a path for life. There’s not much lute on this record, maybe one track, but it’s still a part of my musical life.

Turning to this Schumann project, it’s one thing to know abstractly that Robert and Clara had difficulty receiving consent to be married and that Robert Schumann was overtaken by mental illness, but to watch and hear it play out in epistolary form makes the Schumanns’ story so much more immediate. What did you take away from this project, either musically or extramusically?

I knew Robert Schumann’s music, I never heard Clara Schumann’s music — I knew her name. And I suppose that’s part of the misogyny of music history [laughs]: you would tend to ignore her because she’s a woman. But I was fascinated by her work particularly, and some of the songs are fantastic. What I took away from the whole thing was an incredible sense of sadness — a terrible tragedy those people lived through, and yet [they] created this timeless and eternal music. I have great admiration for that.

A striking line from one of the Robert Schumann letters: ‘Music is nothing more than resonant light.’ I know that for you music has spiritual significance.

I think ‘resonant light’ is exactly right; scientifically, it’s a waveform just as light is, just a different part of the spectrum. I don’t know whether he knew that or whether it was just a poetic intuitive image but certainly it’s true scientifically. But yes, my spiritual life, if I have a spiritual life, is one of music. I seem to be, through music, in touch with something bigger than myself or bigger than the material world. I wouldn’t want to be more specific or detailed about it: it’s a spiritual path, music, classical music probably closer than anything else.

Why is that?

I think it’s really about the higher emotions, about the heart and the intellect at a very high level. It’s not really about the lower chakras, it’s not really about humping your girlfriend — and there’s nothing wrong with that, there’s a place in music for that. But classical music does tend to be higher in this sense. What it wants to achieve or what it wants to say about the human condition is, I think, rarefied — and I’m attracted to that.

Do you think it’s a music that we are naturally drawn to as we grow older?

I don’t think you have to be old to appreciate classical music, but yeah, in my path, it’s becoming more interesting to me. There’s certainly more to learn. If you want to learn arranging, then listen to Ravel. If you want to learn harmony or counterpoint, listen to the masters. I love Chuck Berry, but I’m not going to learn much harmonically from a twelve-bar rock song.

Before the Dowland record, were there certain classical works that were an entrée for you into classical music?

Well, I’ve borrowed bits of classical music before; I famously borrowed a piece of Prokofiev from the Lieutenant Kijé Suite, used as the love theme for my song “Russians” (I always quote my sources, I wasn’t ripping it off wholesale without saying that). A piece of Hanns Eisler for a song I wrote called “The Secret Marriage” — it was very chromatic. I sort of pick and choose things that I can deal with and utilize in my fashion. But I’m not a classical musician; I just appreciate it, and there are certain parts of it that I can... use.

How did If On a Winter’s Night come about?

It was suggested that I do a Christmas record, and I didn’t really like the sound of that. I said, “What do you want, ‘Chestnuts by an Open Fire’? ‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’? I don’t think I want to do that.’ But if ‘Winter’ was the concept then I could bring in far more disparate elements. Say there’s a link between the Christian story and stories that are pre-Christian, the pagan idea of Regeneration as opposed to Salvation, which is what the winter festival is about: You deal with the past in order to move into the new year. All of the songs, even the Christian story, have that at their center.... It’s dark; it’s not a jolly Christmas record at all. I think it’s moody, it’s the sort of thing you want to listen to with a fire going on a dark night. [Laughs.]

My spiritual life, if I have a spiritual life, is one of music. I seem to be, through music, in touch with something bigger than myself, or bigger than the material world.

Is the album title a Calvino reference?

Yeah, it is, If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler. It’s a very interesting book. For me it’s about authenticity. You’re constantly wondering, ‘What is the authentic book inside here?’ You’re constantly being turned around: ‘Well, this is not the authentic book, it’s a different kind of book.’ So it does apply to the album in that sense. Is any of this authentic? Is anything authentic? [Laughs.] What is authenticity?

Let’s talk about some of the more classically flavored morsels on this collection. What was your experience with Purcell’s ‘Cold Song’ from King Arthur?

I adapted it slightly, I took out the ‘ah-ah-ah-ah . . . ’ I sang it that way originally and thought that it was really taking away from the melody, for me, anyway. So I took the basic melody and thoroughly enjoyed singing it. I love Purcell. I find him very modern in a sense, his chromaticism, some of the harmonies are quite extraordinary. And I love the lyric.

That walking bass line, too. . . .

Yeah, it’s terrific. He had some good bass lines, Purcell. Music for a While — it’s one of my favorites.

You included a song from [Schubert’s] Winterreise.

It would have been strange to have ignored that, because it’s really a model for this whole project, which is a meditation on winter — you have to look at it somehow. So I chose one [“The Hurdy-Gurdy Man”] that I was able to do, translated the lyrics — not because they’re terribly difficult to translate — took some liberties with the dogs, and fit it in to the folk thing, with a squeezebox and a voice. It’s not high opera, it’s a man on the street — I can play that role.

And the Bach Sarabande from the D Minor Suite?

I was very familiar with the Cello Suites, in fact I played all of them on guitar. You wouldn’t want to pay money to hear me do this, but I can get through the whole of the Cello Suites. So I only knew it as a solo piece, but then I heard a piano version of it by Herbert Fryer, an English composer, done around the 1920s, harmonized, and it really struck me. So I thought, maybe there’s a song there, and I lived with that for weeks and weeks until this story came out about a journey in the snow — and it just seemed to fit the whole project.

Are there any other composers you particularly admire, anyone you’re thinking of exploring further?

I’m not going to tell you that! They’re going to board up the house and I’ll never get in! I’m not going to tackle Puccini, I’ll tell you that. Or Verdi. Or any of those guys.

Fair enough. Do you feel you’re entering more of a baritone phase now? Exploring more of that color?

Yeah, I’m exploring the darker, lower reaches of my voice as well as trying to maintain high C’s and D’s, which I can still do. But I think it’s nice to have that stretch. As you get older, it’s probably more fitting to sing a little lower.

Like the natural operatic progression —

[Laughs.]

— where you do the hero tenors as a young man —

I’m not gonna get way down there. I don’t think I can do that. But it’s a nice thing to be able to do, especially with a microphone, a close mic. You can sing quite quietly and deeply.

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine -

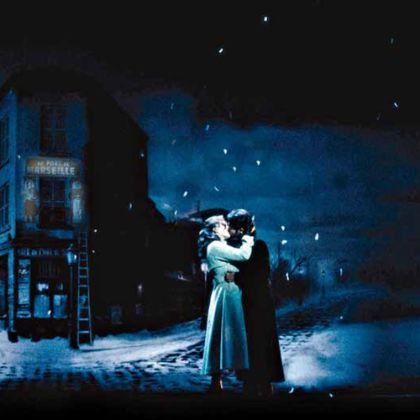

A Simple Love Story

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine