isabel leonard discusses dance training as character building, singing as expression, frozen versus the magic flute, mozart and rossini as base building, trouser roles, and contemporary opera.

By Ben Finane

A native New Yorker, mezzo-soprano Isabel Leonard made her Metropolitan Opera debut in 2007 as Stephano in Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette and starred in 2012 as Miranda in the Met’s premiere of Adès’s The Tempest. She opened the Met's current season as Cherubino in Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro. Leonard has also released a children’s album: The Polar Express / Gertrude McFuzz (GPR Records).

You’ve had dance training at the Joffrey Ballet School. I don’t think many people realize that a lot of acting is movement — and nonverbal. I would imagine onstage that dance experience really helps.

When I think about my dance training, I realize how lucky I’ve been to have it. At this point in my life, I can go into a dance class and enjoy myself but also take the class seriously; I can continue to work on the little things. I’m never going to be a professional dancer — I don’t want to, nor have I ever wanted to — but it’s nice to have that coordination, and to be able to do any step in a pinch. When I’m studying for a new role, I watch other people — characters in a book or a film, or even just someone on the street. I draw from them for the characters I play. It’s really easy for me to see what they’re doing because I can break it down: when they walk, do they lead with their hips, or with their stomach? Which side do they favor?

Where’s their center of gravity?

Yeah, exactly! Which arm is stronger? You can observe these things—

And it helps create a character.

Yeah! And if I’m creating a character that I’ve done many, many times — for example, Cherubino is a big one in that it’s so physical and so obviously different from who I am. He has become a character who I can interpret in lots of different ways and who I’m happy to perform differently every time. What’s most rewarding is hearing the director’s ideas and concept for the production and going from there. You have to start at the psychological level. Who do they think the character is, and how do you manifest that physically? Then I go to work on particular scenes, even if it’s just mulling things over in a coffee shop.

Is a character totally new each time then?

No; once you’ve sung a role the first time, there’s a foundation that you can’t help but build off of. Saying that there’s a clean slate is kind of a lie, because ultimately we’re the sum of our experiences. Again, with Cherubino, I try to approach him psychologically. So aside from being quite outgoing, the character is also shy in certain circumstances. When he’s shy, what does that mean physically? I play with ideas and movements, and eventually I hope that it becomes part of the character. I just have to respond the way Cherubino would respond, not necessarily how Isabel would. You develop a vocabulary in your body for characters that shows who they are and how they respond to things — what makes them happy — and when it happens, your body reacts. So I’m sure that dance has had a huge influence, even just in developing the ability to use my body.

The bar for acting in opera keeps getting higher and higher, especially given that it’s contending with television and film. We’re used to hyperrealism and demand more physicality, more believability from people on stage — especially as couples. Does the acting and the singing become one thing in preparation?

I think the singing is a vehicle to express the emotions and thoughts of the character. If those two are disjunct, there’s a great piece missing from the performance and you do a real disservice to the audience. You know when you hear a baby cry, you know how they feel because of the sound they make — before you even look at their face! The reason we turn our heads when people yell is out of doubt, really. We doubt what we hear since the causes of those exchanges change so much with age. But I think it’s very much a part of the character.

It’s actually something I’ve been toying with recently. Your voice is your voice. And when you study or you coach, everybody says, ‘Don’t manipulate your voice.’ Don’t change it or sing differently than you normally would, because it’s your instrument and it’s not going to sound like anybody else. It’s you, and I think that’s very important. But there’s that part of me that thinks that even though we’re accustomed to hearing beautiful operatic sounds, there are times in opera and in music when it doesn’t have to be beautiful. I don’t meant that it has to be purposefully ugly or shrill, but if the character is obviously wailing in the music, that needs to come through somehow, especially in big opera houses like the Met where you can’t always see the actor’s face. It’s actually a really good thing that we can sing as loudly as we sometimes do, because people who can’t see us can feel the emotions we’re trying to transmit.

I would think that it’s more common in musical theater to sacrifice beauty for character. That is still tough in opera though, because we’re going to hear a singer, and even if she is playing a character — we want to hear her voice. I think there’s a certain expectation of beauty there.

I think so, too. That’s what opera is and that’s okay. Ultimately, when I say an ‘ugly sound,’ it doesn’t mean an untrained voice, or a voice without technique. Everything still has to be used properly and healthily. I don’t want there to be any misconception there. I guess because I have a four-year-old I think about this a lot, but kids are drawn to the visceral and soulful things! They would never tell you that that’s why, but they love it. They get it! If it’s not real, they’re not interested. I think of all the little kids I know, singing the Idina Menzel song from Frozen [“Let It Go”]. She may not have the most beautiful voice ever, but she sure does have a lot of soul, a lot of passion and sincerity. There’s so much in there that’s really musical, and that’s why all of those kids — boys and girls — are singing that song. That surprised me, because it’s been a while since I’ve heard kids singing Disney tunes, and I was trying to figure out why. I didn’t understand until finally I saw the movie with my son, and I was genuinely touched by the song. The story is whatever....

It’s a true aria: it sums up what’s happening in the movie, but the viewer can also put it in the larger context of his or her own life experience.

Yeah, and it’s interesting stuff. My son and all his friends from preschool were singing this song, and I think it relates directly to what we have to do in opera.

Do you think there’s a barrier to entry in opera? I see it — and ballet — as these niches, but niches that flourish because of support from lifelong students of the art. Every former singer, every ballerina continues to see ballet and opera until they die. And you can see it in the audiences, these former dancers at whatever level — amateur, professional. But the kids you mentioned, they sing Disney tunes and maybe go see The Nutcracker.

Well, my son walks around the house singing Papageno’s aria in English because he loves it. It can be done, they just have to be exposed to it and allowed to explore it in their own way. They should be allowed to like whatever they like, and it shouldn’t be made into such a strange thing. It’s a show! Why wouldn’t a kid like the lights and costumes? And a live orchestra where they can look into the pit? Kids want live entertainment. I mean yeah, they love TV, but there’s a reason puppet shows still exist. I took my son to see The Magic Flute in a dress rehearsal at the Met with one of his preschool friends and they sat through the entire show! Recently we were staying with some friends and he asked their daughter to play a song. He started humming ‘La donna é mobile.’ He couldn’t remember what it was called, but he kept humming it. I had no idea where he found that!

When I spoke with Jonas Kaufmann, we talked about how opera singers are always on a five-year plan — that you need to know now what you’ll be doing in 2018 and 2019. Do you see a tentative path ahead for rep that you’d like to broach or a musical path you’d like to take?

Well I’d say between now and 2018 there’s a lot of new stuff — not just new contemporary rep, but new roles. I started working when I was twenty-four — that was my debut at the Met in 2006 — eight years ago. The first five years or so I was building a career, learning the roles that you need to get under your belt. All the Dorabellas, Cherubinos —

Let me stop you right there. Roles that you need to get under your belt. What does that mean in your case? Is Mozart the starting point?

A lot of Mozart and Rossini.

Why are those the foundation? If you can speculate....

I don’t know, because frankly they’re all really hard. Generally speaking, most people think that Mozart’s Zerlina, Dorabella or Cherubino are more second-lady roles, meaning they’re not as stressful and the orchestra isn’t as loud at those points. So you’re not going to be pushing yourself in the wrong ways. It’s a way to start a career, start working. You can always keep learning repertoire, and those roles aren’t going to ruin your voice.

Even in Mozart’s great operas, there are long periods of recitative. How do you handle that? I’ve seen productions where singers clearly work on their arias, but the recitative almost sounds like it’s being sight-read. How do you give that its due attention — how do you propel things forward?

I love recitative, personally. I would do a whole show of it, but you really need a responsive acting partner. If the person you’re talking to doesn’t hit the ball back, it makes things really difficult. But for me, it’s all about getting into the language, which is usually Italian, and separating small thoughts from big ones. If I’m saying a single paragraph with three different ideas, it’s kind of like a melody. I need to know where I’m going, and if I do, I can direct the line. I’ll try different variations of timing and allow the character to inform my decisions. And that changes in performance: sometimes I have a lot of energy, so the recit will move more than it would on another night. And that’s ok! The most important thing is making it true to the character in that moment.

Have you been digging the ‘trouser roles?’

Yup, I’ve done a bunch. Cherubino, Ruggiero in Alcina, and Sesto in Giulio Cesare. I find most every role I do interesting. Over my first four seasons at the Met I did Stefano, then Zerlina, and then Cherubino and Dorabella. Those are my four seasons. My big fifth season was Rosina, and that opened the door to other, more demanding roles. After that it was The Tempest, more Rosina, Blanche; doing roles I already knew and adding in some newer ones. These next five years will be almost like a repeat of those first few years, but with all new repertoire.

My son walks around the house singing Papgeno's Aria in English because he loves it... they just have to be allowed to explore it in their own way.

What’s the most challenging thing when you have to approach a new role? One you’re simply unfamiliar with, not even a premiere. Where does the most effort go, and where do you start?

It always feels so overwhelming at first. Any time you do a new piece, whether you know it or not, it feels like you’ll never understand it. I know this about myself, so I always start by telling myself that I will get it eventually. I always do.

I know from my experience in theater that by the end of a show you know everyone’s lines. Is it the same in opera? Do you know every note of the music?

For the most part, particularly if I’ve done the role a few times. But the first time around? Probably not. I would say it takes a good ten shows of anything to really get it into your system. After that you don’t really have to think about it anymore, and once you’re there your brain really starts to open up. Even though you know what everyone is saying around you, it changes — shifts and evolves into something that isn’t a part of your conscious thought process anymore. It’s just ‘there.’

Like muscle memory.

Yeah. I find myself going through this thing with Rosina where everything is starting to sound the same. I don’t mean that all Rossini sounds the same, but that since I know the music so well — and I know everyone else’s music so well — that it’s hard to tell sometimes what’s mine and what’s not mine! There’s a feeling of familiarity with all the material, so if I sing a line and it is mine I second-guess myself. If it isn’t my line, well, that’s a totally different problem. There’s definitely that fear with a new role though. I remember learning The Tempest, thinking that I would never get it. It’s so hard!

Where does Adès’s musical language sit for you, as far as entering his sound world?

It was a huge challenge. Although once you know it — and even listening to it on the recording — it makes sense. But learning it was very, very difficult, particularly the opening section. They were the most unpredictable lines I had to sing. But eventually I found the patterns that I knew would be there. I knew that a certain kind of phrase was being repeated, even if it was in a slightly different way. But until you learn it, you have to remind yourself of that.

It’s funny; I think that non-musicians may not know that even the most difficult musical language is ultimately governed by these patterns and recurring ideas.

For the most part. There are some composers who don’t do that at all, and it’s very frustrating.

At that point you just have to learn it by rote. That’s tough.

I’m a big harmonics person, not melodic lines. I don’t know if anyone else explains it this way, but it’s how I’ve always explained it to myself. In choir, I never sang top soprano because I was a good enough musician to sing one of the inner voices. So I was always in the midst of harmony — which was great, because I learned to pick notes out of chords. But when I’m in a piece with a debatable harmonic language, I have a difficult time learning it. When I sing something like Mozart, I feel like I can latch onto clear handholds as the music goes along. With a piece that lacks that, however, I keep grasping but it takes so much longer to identify those handholds. Usually what I end up doing with these works — and I struggle with this, too, because I’m not a great pianist — is to find a pianist to parse out the structure of the piece, even to the point of rewriting it into what you might call Romantic harmony. For whatever reason, it’s very difficult for me to learn a melodic line when I can’t connect the first note of the phrase to the last note in my mind. I need to know where I’m going, and when I don’t it feels very uncomfortable, and that’s hard to sell on stage. I have to be able to sing it. Pavarotti used to say that: ‘Just sing! Just sing!’ If I can get someone to strip it down, though, I can learn to hear that more traditional harmony through the written textures, and I know where my note fits. What I sing is always part of something; it’s not a solitary sound. It also helps with my intonation. I tune based on what I hear around me, so if I’m singing with someone who is consistently flat, I will sing flat with them.

So it’s more relative than saying ‘This here is my A.’

Absolutely. And I don’t have perfect pitch.

The great thing about singing contemporary pieces is it's basically an intense ear training exercise. The repetition and parsing of the harmony really helps me learn the music on that deeper level.

I don’t think perfect pitch is always an advantage, especially for singers. You brought up a great point though, in that singing a difficult line is so much harder than playing a difficult line on the piano, because on the piano you can play, say, minor seconds and tritones without having to own and ‘know’ those intervals — the instrument is going to do that for you. But If you’re singing something, it’s almost like you have to be the composer and understand why things unfold the way they do before you can project that. I imagine that has to be difficult.

It is. The great thing about singing contemporary pieces is that it’s basically an intense ear-training exercise. The repetition and parsing of the harmony really helps me learn the music on that deeper level. At the same time, I train my muscle memory to remember what those pitches feel like and what they look like on the staff and in sequence. If you sing Romantic harmonies most of your life, it becomes second nature. I never used to be visually attached to the way a certain pitch felt. That’s changed as I’ve started to work more on contemporary music though. I sang so many A’s in The Tempest that I started to associate the feeling of the note with the pitch name. Something about the way the music approached the note again and again made it important for me to make that association. So now if I sing an A in another song and then transpose it, it feels very uncomfortable if I look at the music because the song doesn’t feel like what is written. It’s a really interesting process, because your body adapts to these different scenarios.

Perhaps with contemporary music, where the harmonies get so complex and the notes so clustered, maybe you have to have that confidence in your muscles —to be able to sing an A even if it’s impossible to pick out from what’s happening around you.

You know, we have these friends from school that were very good when we got to the part of theory with tritones and alternative scales, and who were really good at sight reading. They must have had more perfect pitch or something, and I think those skills really help people who have to do contemporary music, because they already have an idea of where their pitches have to go. But even without that you find your way in.

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine -

A Simple Love Story

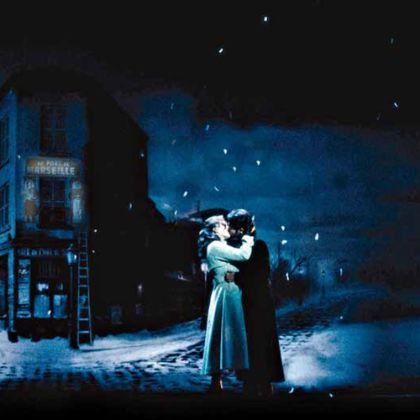

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine