David Robertson on rehearsing, marketing and programming classical music.

By Ben Finane

Photographs by Sari Goodfriend

California-born conductor David Robertson was educated at London’s Royal Academy of Music, where he studied French horn and composition before turning to orchestral conducting. Serving as music director of the Ensemble InterContemporain in Paris from 1992 to 2000, Robertson gained international recognition for his affinity for both twentieth-century music and operatic repertoire. He is currently in his seventh season as music director of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and also serves as principal guest conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Does the American orchestra need to adapt to a changing climate?

I would say that orchestras adapt as a normal result of new musicians coming in who may have a different experience, due to their generation, of what the music world is like. We tend to look at the structures of orchestras and say, ‘Oh, they haven’t changed at all!’ but just in the period of my lifetime, orchestras went from being groups that were beat into shape by the conductor to a network of individually refined artists who are seen as such and who collectively feel responsible for their musical level — and it’s not only the conductor’s responsibility. In the newer generation of players coming in, you see people who understand that their role is not just to play in the symphony orchestra but also to be ambassadors for music in whatever context they find themselves in — playing in the orchestra, riding a bus, working with community projects, helping their kids’ school programs, whatever it might be.

As regards ‘beating into shape,’ I’ve had the opportunity to observe you in rehearsal, where I was impressed by the calm atmosphere, the sense of dialogue and exchange of ideas that held sway.

When I was in Europe, people always used to refer to that as a very California attitude. There can be so much tension and stress in playing music at a really high level, I often feel that a three-hour rehearsal can be like a three-hour tennis match between Federer and Nadal — and they’re trying to do everything perfectly right the whole time, so it can be very exhausting. Therefore, almost like a tennis match, you try and limit any extraneous things that might hamper the players’ ability to do well. And that means keeping it as calm as you can in terms of the process. And that’s mainly because [laughs] in the middle of the music there may be stuff which is anything but calm.

One thing that I have found is very helpful — and I wish that we could do it more in real life — is to focus on the solution rather than trying to define the problem. So very simply, you don’t say, ‘Basses, you’re late,’ you say, ‘Basses, we need more forward motion on that triplet.’ And so, all of a sudden, that’s not looking at the problem as ‘Those people are rushing’ or ‘Well, I thought I was in time,’ or ‘Well, these two notes take more time on the bass than they do on the cello’ — by missing the thousands of ways you could talk about the problem you focus on the one which in the end everyone has to do. There will need to be forward motion on those three notes even in the performance, even when it’s played right. So let’s start working on what’s right, from the start, and not worry about what might be the definition of what was wrong.

So is there a bit of marketing there?

No, not even marketing, it’s a question of the point of view.

Everybody is trying to play the piece as best they can. There are many ways to do that, and I don’t think the conductor has the sole voice of reason there.

A-ha.

Everybody is trying to play the piece as best they can. There are many ways to do that, and I don’t think the conductor has the sole voice of reason there. In St. Louis, for example, if the clarinet plays the theme first, everyone is going to listen to how our clarinet plays the theme. They are actually then going to play the theme like that. And that’s before I say how to play the theme. What I like about that approach is it allows for the maximum flexibility.

Now if something doesn’t work, when I stop, rather than saying, ‘This and this and this aren’t working,’ I say, ‘This and this and this need to be more like this,’ and then everyone concentrates on that! So the question of what the problem was, or even looking at it as a problem, actually disappears.

Nice.

Marketing, I feel, would be if I were trying to sell it — and that’s not actually the reality. Marketing is saying, ‘This food is better for you because we have processed it and we will make money by selling it to you, rather than you just going to a local grower where it tastes really good but we make no money on it.’ That’s marketing. [Laughs.]

OK. Speaking of food that’s good for you, coming from Ensemble InterContemporain to the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra does not permit you to set the table with the same programming.

Right, I wouldn’t be able to, and in fact, with the Ensemble I had the opposite problem: I had to work quite hard and carefully to get some Brahms and Mozart on one of the programs. It made a lot of sense in connection with the music of Ligeti, but because their constitution says ‘music from the twentieth century onwards,’ that could bring a conflict of interest with people saying, ‘You’re not being paid to do Brahms.’ And in the same way, you could look at the programming of an American symphony orchestra and say, ‘You’re being paid to play only things that people like.’ I think that’s not actually the mission of a cultural institution.

And certainly Ligeti doesn’t exist in a vacuum without Brahms.

Right, and in fact no music exists in a vacuum. My wife [Orli Shaham] put it really well. She was asked by a radio station to name her favorite year in classical music and she answered, ‘Well, 2011.’ They were looking for 1878, or Mozart’s bumper-crop year of two quintets and Marriage of Figaro, or Brahms’ birth year, and her response, to me, makes perfect sense: There’s all this music of the past, which when we perform it, is alive; there are all these great performers who are keeping this great tradition going; there are composers who are adding to this tradition all the time; now is the best time for classical music.

I don’t see why a symphony orchestra shouldn’t work the same way. I will say that the audiences have gotten used to coming to a concert to hear works they already know. And this is not purely a classical-music phenomenon. It has often been reported that people who go to hear their favorite group at a pop, rock or even jazz concert will complain that they had to listen to a half hour of new things before they heard a song they knew.

Does this speak to the quality of masterworks?

I think it speaks to the shift in marketing. Any rock band knows now you record the stuff, you send out the album, and then you do the tour, where you play the music in order to promote the album. So you are actually about selling the artifact first and not presenting the music, where people are expected to listen to it and simultaneously make a decision about what they think of it. And that is a huge shift that came about with the advent of mechanical reproduction.

Now people don’t think of going to a concert to hear music they haven’t heard before. Almost without exception, the programs that are presented to any kind of audience are presented in terms of ‘We are going to play these works you already know’ and very rarely is it ‘We are going to play all these works you’ve never heard of before’ because common marketing sense tells us this is box-office suicide. This is why groups like Bang On A Can organize concerts that are so long that even if there are works that you might know on the program, there are so many works that you cannot look at it as familiar territory. But any standard concert from most classical organizations, many rock organizations, many jazz organizations will have standards on the program that they let you know will be played — ‘You will certainly enjoy these!’ And depending on how adventurous they are (and I think jazz players are the most adventurous in this way, which I think also accounts for the relatively small size of their audience, like that of classical music when compared to Lady Gaga) it means that you run the risk of alienating people who are not used to listening to music that they don’t know in a concert setting. And this is aside from asking them afterwards if they like it!

OK, but there are certainly no top-forty or even well-known works in your discography. So how do you record — and program — such little-known fare without frightening audiences or alienating meat-and-potatoes listeners?

You need to essentially build up a sense of trust. You cannot generalize on people’s tastes. The French phrase chacun à son goût [each to his own taste] is absolutely true and one is surprised at different people’s blind spots. In my case, I love Aubert and Rossini and all sorts of people, so that you’re surprised when it turns out I hate Gounod. And there’s nothing wrong with Gounod, it’s just that I personally do not get it. Everyone will have things like this.

So given that you can’t get people to trust in terms of taste, you can get people to trust in terms of level of quality. And so even if it’s something that you’ve never tried before, you can be certain — like at a restaurant — if you try it here, it will have had the best preparation. And if you like it, that’s great. If you don’t like it, your time has not been wasted.

Let’s go back to musical durability. You’ve mentioned ‘pop’ music. And I’ve always thought of pop music as music that sounds great the first time you hear it and then offers diminishing marginal returns during subsequent listens until you hate it — whereas the opposite would hold true for music that lasts.

Right.

There are works which are not necessarily easy listening, which if you program them correctly, and perform them with passion and commitment, the audicence will understand that something really special has transpired.

In my writings about masterworks, I remind readers that great works last because their craft and substance permit them to be viewed from myriad angles. But you made an excellent observation on the quality of a masterwork [in an interview with Joshua Cody of the Sospeso Ensemble — see sospeso.com]: ‘A great painting, whether abstract or figurative, has elements so rich that it is constantly changing, because you are constantly changing; it’s rich enough to accommodate your own development.’ And I prefer that, because you’re saying it’s not the work that’s malleable, it’s rather the viewer — or the listener.

It’s us, yes. And what you’re talking about — and I agree entirely — is for me the actual definition of art, in whatever form. It is that the work aspires to art [and] there is a richness that warrants repeated interactions with the work.

I don’t limit that to classical — certain of the Lennon–McCartney songs, certain Paul Simon songs, certain works from jazz masters, as well as Schubert, as well as things not from the European canon have this quality. And the same with a painting, or a drawing, a work of literature, or dance —

Certainly this quality transcends genre.

Right, exactly. That’s where, for me, the magic takes place: we are not the same people from one moment to the next, and therefore our experience of it can change.

I see this every time I rehearse an orchestra on a piece of music. At the first rehearsal, they have one collective experience of it. And by the time they arrive at the performance — and if we’re lucky, many performances — the collective experience has changed and deepened in ways that you cannot predict when you first start rehearsing it.

Returning to marketing food that’s good for you, is there an imperative to push contemporary music? Is it a conductor’s responsibility to push music of our time, even if it runs contrary to prevailing taste?

This is a thorny issue because here we get into questions of style and taste. I think it is important for people to be exposed to music of their own time, but I have a very high standard for that. There are people who like the sound of different kinds of music. There are people who like, say, the all-over quality of free jazz or of certain types of very dense, complex music. There are other people who like the almost monochrome simplicity of certain types of music or certain types of painting which are very slow in terms of their changes. And there’s everything in between.

So my stance is that the interpreter, whether conductor or instrumentalist or theater director, needs to have a compendium of knowledge of what is out there, and has to constantly look for opportunities in which a work that has depth will attain meaning when presented to an audience in the right context.

I extend that also to works of the past. Let me give you an example. There is a wonderful Russian composer who is virtually unknown in the United States. He died relatively young. He was beginning to write at about the same time as Rachmaninoff and Scriabin were beginning to write. He was a little bit older. His name was Vasily Kalinnikov. He wrote a couple of symphonies. The first symphony is a real gem, but it is forty minutes long, and with classic second-half positioning after intermission in your standard orchestral concert, no one will come to hear it. They will have a really great time, but no one will come to listen to it. Because they’re scared of a piece they haven’t heard and there are other things impacting on their time, and so they’ll choose the one where they know they’re probably certain to have a good time.

And so I used this as my opening concert — this past season we [the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra] had a Russian festival. I began with the Kalinnikov symphony. After the intermission, I had Prokofiev’s Lieutenant Kije Suite and then Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto. Now, the Kalinnikov first sounds like what might be a Tchaikovsky Seventh Symphony, and everyone in the orchestra came to it fresh — except for our one Russian player — and they were all blown away by how wonderful it was. And the audience were all standing on their feet, having a great time. But this took my waiting for six years to find just the right moment where I could put this work in front of the public and have them say, ‘What a great piece of music!’

Now, there are works which are not necessarily easy listening, which if you program them correctly, and perform them with passion and commitment, the audience will understand that something really special has transpired.

I’ll give you an example: Schoenberg’s Erwartung [which Robertson recently conducted with the New York Philharmonic and Deborah Voigt] is not easy listening at all, but if you get a really good soloist and a high-level orchestra that can make these cinematographically quick changes that Schoenberg asks for, you get an experience in music that is unlike anything else. For me, the deciding factor is: is this piece, contemporary or from the past, unique in such a way that it is irreplaceable, that nothing else can do what it does? Then it’s worthwhile playing. And it’s important to put that out to the audience — whether its Schubert’s Eighth Symphony or Kalinnikov’s First Symphony or a work by Shostakovich or Britten or Kurtág or Luciano Berio or Nico Muhly.

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine -

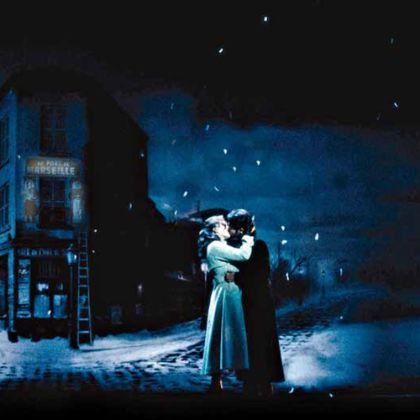

A Simple Love Story

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine