Israeli mandolinist Avi Avital discusses the rich history of his instrument; the nonexistent border between folk and classical; transcriptions and commissions; embedding nuance; and the artistic persona.

By Ben Finane

Avi Avital was born in Be’er Sheva in southern Israel, where he began his mandolin studies at an early age and joined a mandolin youth orchestra. Avital went on to study at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and then the Cesare Pollini Conservatory of Music in Padua, Italy. Approachable and unfussy, Avital spoke to Listen at the New York City music-and-arts venue SubCulture.

The mandolin has been around for quite some time.

Indeed! The mandolin began to gain popularity in seventeenth-century Italy and comes from different plucked-string instruments that were already around in Europe during the Renaissance. But the word mandolino first appears in the Medici court in the beginning of the eighteenth century. At first, we had many types of instruments all named the ‘mandolin.’ The mandolin in Venice was different in shape and tuning from the mandolin in Naples. What was common to all was that they were plucked-string instruments. What we know today as the mandolin is the Neapolitan mandolin, which is to say eight strings — or, more accurately, four pairs of strings with each pair playing the same note, tuned like the violin, in fifths: E–A–D–G. Metal strings played with a plastic pick.

Yet while the mandolino came from Italy, the instrument remains at home in many cultures’ folk traditions.

There is a good reason for that: if you look back at almost every ancient culture in the world, there is a plucked-string instrument that may look or sound like a mandolin that plays a main role in that culture. In Russia it would be the balalaika, in Greece it would be the bouzuki, the tambura in the Balkans, the bandurria in Spain, the oud in Muslim and Arab music, the pipa in Chinese, the koto in Japanese music, the tar in Persian music, the banjo in American music, the charango in South American music and so on and so on. And that’s why the mandolin, as a Western modern instrument, has a bit of this ancient-culture quality. When I play Russian music on the mandolin it dialogues with the balalaika because the sound is similar, and therefore it sounds Russian. When I play Italian music, it sounds very Italian.

In the strictly classical realm, there’s not much repertoire for mandolin.

Not at all. Unfortunately, the great composers — Bach, for example — never wrote one single note for mandolin. That’s tragic. People tend to think that’s because the mandolin wasn’t so popular. But I think it’s because the mandolin was very popular, so popular that it was considered more an amateur instrument than a classical or orchestral one. Therefore, composers didn’t relate to it as a professional instrument.

Like the guitar today, it’s by far the most popular instrument: if you combine the popularity of classical guitar with that of the guitar you take on a school trip or to play with friends around the campfire, it’s far more popular than the violin or piano. But that’s the reason why it’s far more connected with popular music than with high-art music.

That said, you’re still ‘classically trained’ in mandolin. What exactly does that mean?

When I was a kid in Israel I went to the local conservatory — it was something to do after school when you are eight. I started to study the mandolin and only found out as an adult that my teacher had been a violin teacher, so he had really educated me and my class to play classical pieces, especially those written for violin. And that was my introduction to classical repertoire.

Your first album for Deutsche Grammophon was Bach transcriptions. When you’re transcribing a piece for harpsichord, it would seem on the surface that you’re at a disadvantage — you have ten fingers at your disposal, as opposed to one hand —

[Avital holds up four fingers.]

Four fingers! So how did you get this done? How did you overcome the obstacle of the instrument?

Yeah, I really enjoy the process — even the intellectual process — of adopting the pieces for mandolin. The easiest way to go is to take violin repertoire. They’re tuned the same; you don’t have to do any arranging. You play it from the score. It sounds different — the music is in a different light, but technically it works. The way the left hand acts is almost identical to what a violinist would do.

With harpsichord, I have to take one of the hands out and really reduce it to its essence. Now, I have to say that the D-minor Concerto for harpsichord that I recorded is originally believed to have been written by Bach himself for violin, and afterward he transcribed it for harpsichord. Obviously, the version for violin did not survive and it’s only a theory, but it makes a lot of sense because the music just fits on an instrument tuned in fifths. The essence of the music is very melodic, although there are a lot of harmonies, but you can still maintain the whole piece — twenty-two minutes, a huge architecture — you can still maintain the tension of it and the sense of it by reducing or summarizing the essence, the important content of the music. So it’s very virtuosic, very difficult, but it still works even though you don’t have two hands working for you all time, like with the harpsichord.

I of course came to the piece having a harpsichord — or piano — version in my head. But after hearing it you have to admit that the mandolin maybe has an expressive advantage —

[Laughs.]

— over the harpsichord. And, like you said, since it’s all about the melody, to hear those melodies on mandolin is an ear-opening experience.

Yes, that’s exactly the point I was hoping to make. Instead of just playing music on a mandolin because there’s no repertoire for the mandolin, it’s about hearing pieces you know or that your ear is used to in a different light, from a different perspective. I think mandolin is very nice way to listen... especially to Bach, because his music goes beyond the instrument in its universality. With a fresh ear, suddenly you hear inner voices that are not necessarily coming through with a violin or another instrument that our ears are more used to hearing. As an artist, it’s a privilege to be able to offer such a fresh perspective.

Your most recent album, Between Worlds [(Deutsche Grammophon)]. I’m looking at the cover here.

[Laughs.]

You’re leaping between heaven and earth; you’re straddling the yellow line of the road. It’s clear that you’re making a statement about crossing borders, but I imagine it’s pegged to something a bit more specific.

It reflects the idea of playing with the border, the unexisting border, between folk music and classical music.

There’s an interesting bit of intentional phrasing. Tell me why you feel that border is so permeable.

We consume entertainment — pop music, TV series, funny movies — because it’s enjoyable. With art, there is an extra component, a spiritual component — extra value added. We all know the difference between a pop song and classical music, a movie and a film, going to the disco and going to the ballet. We need both entertainment and art in our lives. Although it’s not a thick border, there is a functional difference: we all need that spiritual component in our lives, and art is one way to add that value. That’s how I see my role when I play classical concerts. Folk music, traditional music, shares that same function in life. It was more obvious in the old days, in ancient history, when music was the spiritual component used in religious services: shamanic music in ceremonies to create ecstasy and uplifting effect. And later on, art music as we know it grew out of a religious function. That’s why folk music/traditional music and art music/classical music share a lot in this sense. It’s [all] music and it moves you in a spiritual way, hopefully.

We all need that spiritual component in our lives, and art is one way to add that value.

I think a great jumping-off point is the Bartók, the Six Romanian Folk Dances, which were written for piano but when you hear them on the mandolin sound as though they were written expressly for it.

[Laughs.] Thank you; that’s a good compliment. Definitely: Bartók is the symbol of this album; this is the first piece that started the idea [for the recording], the first inspiration that I had. He wrote this piece exactly one hundred years ago in 1914. And I tried to imagine sitting in a piano recital in 1914 at Carnegie Hall, say, and listening to Brahms, Beethoven, whatever — and then suddenly hear folk music played on a piano. Exotic modes. Exotic rhythms.

Could have been written yesterday.

Yes, indeed, but at that time it was so modern and so advanced for Bartók to take folk music and put it in a concert hall, something that in 2014 is unusual but not unheard of. We now know much more about other cultures than people did a hundred years ago. If you ask ‘What is a Romanian folk dance?’, everyone has a vague idea of how it may sound or look, and if not you have YouTube — and with one click, you’re there. So in this sense we are privileged. But back then, I’m sure it was extremely advanced to bring music from remote villages in Romania and Hungary and all over the Balkans and translate it into something so classical — like music for piano, string quartet, symphony orchestra, which he also wrote. So taking something very folk and making it a concert, art music — that was very inspiring for me. And I thought, how can I make it modern again in 2014? We don’t necessarily think of Dvořák and Bartók as the most imaginative, but they were. And I wanted to capture their inspiration as well as the identity complex they had in dialoguing with their own folk culture and putting it in the context of a Western classical concert hall. That resonated with my own identity and path as a mandolin player and as an artist who enjoys playing classical music and other genres.

The Six Romanian Dances are paired with de Falla’s Siete canciones populaires españolas. Here are other folk miniatures — but coming from a completely different aesthetic.

Yes, in fact the de Falla Spanish songs were composed exactly the same year as the Bartók dances. Like Bartók, in 1914 and 1915 de Falla took folk melodies and, like Bartók, kept the melodies exactly as he heard them, but the original treatment is in the accompaniment — changing the harmony, the structure, the bass. So this changes the color of the melody, which remains intact. Very different: de Falla is Spanish; Bartók is Hungarian — and you hear that immediately. Even their treatment is different. But all the composers on this album — in different places in the world, at more or less the same time — shared this passion to dig inside their own culture and bring it into their art.

When you approach all these cultures — beyond what we’ve discussed, there’s klezmer, there’s the Georgian sound world of Tsintsadze, South American, Dvořák’s American bohemian — it’s not like you can say ‘I’m just going to be Avi on all these pieces.’ You have to inhabit different traditions, and I imagine that each tradition requires a unique approach.

Yes. Each piece on this album was a response to twentieth-century composers who composed classical music inspired by folk music. But I wanted to take each of the composers’ treatments, dissolve it and reconstruct in my own imagination as to how each composition would have sounded originally. It’s a bit like learning a dialect for each: when you play folk music, it has a lot to do with the nuance, with the accent. I lived in Italy for eight years and I was coming from Israel, where everyone speaks modern Hebrew in more or less the same accent — with no dialects, as it’s kind of a new spoken language. I was astonished to discover that in Italy every region has a language, has a dialect. Every village has nuances — within twenty kilometers, the dialect changes a little bit. When they all speak proper Italian, they have different accents. I really enjoy tracing these nuances, those little things that make it characteristic. So a trill or ornament in klezmer music would be different if it’s Bulgarian klezmer or Romanian klezmer or Russian klezmer. The accent is different. And to try and imitate the accent of a spoken language in music — because folk music is driven a lot by the language of its origin. That was a layer I really wanted to put into it. I remember in the Spanish folk songs, it was really about imitating the human voice and a Spanish cadence, a Spanish accent — a Spanish melody of singing and speaking as well.

So sometimes speaking Mandolin with a Russian-klezmer accent.

[Laughs.] Pretty much.

‘It’s not about imitating accents: it’s about embedding nuances. it’s like a painter who has two colors or thirty-two colors and can mix them.’

Does your instrument have a voice if you take all these accents away and you’re not looking to get into character for a piece: do you have a natural voice as a player?

Absolutely. In all those pieces, it’s my voice. It’s not about imitating accents: it’s about embedding nuances. It’s like a painter who has two colors or thirty-two colors and he can mix them. An artist, an actor, a dancer — all his life he collects more tools of expression, experiences, metaphors, and what have you, but of course it’s all embedded in his artistic persona.

You’ve commissioned some works for mandolin, perhaps in a desire to increase the bedrock repertoire. What do you look for in a composer, in a project, when you’re giving a commission?

I give carte blanche to composers. I like a lot of streams within modern, contemporary composition. I tend to commission composers who have markedly different approaches to music: some are very avant-garde, some are very folkloristic. I enjoy seeing what associations come to their creative mind when they think ‘mandolin’ without my conditioning them.

After getting a new piece from a composer, do you encounter the difficulty of ‘Oh, this part isn’t technically playable!’

Almost always.

What happens then?

[Laughs.] It’s a funny question. The reason I took on this life mission to expand the repertoire of the mandolin, which was on hold for so many years, is because through repertoire — and the history of music teaches us this — the instrument develops.

There are so many times when I get a PDF from a composer and I look at the first page and say to myself ‘Come on, this impossible to play! I have to phone him back.’ Then I say ‘Come on, give it twenty minutes,’ and then I can often find a technique to make it work. I have to remember: ‘You don’t know everything about the mandolin.’ Sometimes a composer who doesn’t know anything about the mandolin can be very creative and reveal some of the surprises that the instrument still holds for you — and that’s a great satisfaction.

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine -

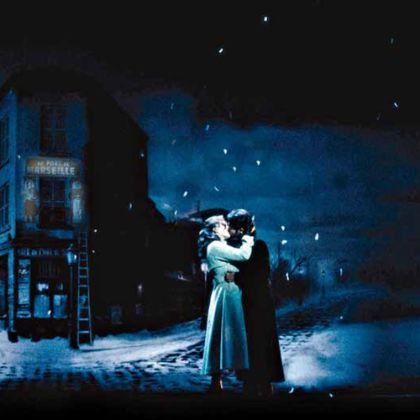

A Simple Love Story

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine