What Hemingway can teach us about performing-arts criticism

By Ben Finane

The bull-fight on the second day was much better than on the first. Brett sat between Mike and me at the barrera, and Bill and Cohn went up above. Romero was the whole show. I do not think Brett saw any other bull-fighter. No one else did either, except the hard-shelled technicians. It was all Romero. There were two other matadors, but they did not count. I sat beside Brett and explained to Brett what it was all about. I told her about watching the bull, not the horse, when the bulls charged the picadors, and got her to watching the picador place the point of his pic so that she saw what it was all about, so that it became more something that was going on with a definite end, and less of a spectacle with unexplained horrors. I had her watch how Romero took the bull away from a fallen horse with his cape, and how he held him with the cape and turned him, smoothly and suavely, never wasting the bull. She saw how Romero avoided every brusque movement and saved his bulls for the last when he wanted them, not winded and discomposed but smoothly worn down. She saw how close Romero always worked to the bull, and I pointed out to her the tricks the other bull-fighters used to make it look as though they were working closely. She saw why she liked Romeros cape-work and why she did not like the others.

Romero never made any contortions, always it was straight and pure and natural in line. The others twisted themselves like corkscrews, their elbows raised, and leaned against the flanks of the bull after his horns had passed, to give a faked look of danger. Afterward, all that was faked turned bad and gave an unpleasant feeling. Romero’s bull-fighting gave real emotion, because he kept the absolute purity of line in his movements and always quietly and calmly let the horns pass him close each time. He did not have to emphasize their closeness. Brett saw how something that was beautiful done close to the bull was ridiculous if it were done a little way off. I told her how since the death of Joselito all the bull-fighters had been developing a technic that simulated this appearance of danger in order to give a fake emotional feeling, while the bull-fighter was really safe. Romero had the old thing, the holding of his purity of line through the maximum of exposure, while he dominated the bull by making him realize he was unattainable, while he prepared him for the killing.

— Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises ©1926 Charles Scribner‘s Sons

Jake would have made a hell of a dance critic. Between the lines of Hemingway’s trademark lean prose lies an inherent sensitivity and critical instinct: not only does Jake expertly discern between authenticity and fakery, but his observations to Brett never stoop to pedantry. Instead, he takes her own intuition and affirms it, using it as a foundation on which to deconstruct the bullfighter’s movements, focus Brett’s gaze and reveal the artifice behind the spectacle. Notably, he accomplishes this last point while increasing our understanding and — equally important — appreciation for the art of bullfighting.

Music critics today could use a lesson from the American master. Too often we see verbose reviews — crammed with historical background on the orchestra, a biographical thumbnail of the composer, program-note level description of the performance history of the work in question, observations on the mood of the crowd and a snapshot of the weather conditions outside the hall — crafted by Biographer critics, who say much but refuse to take a critical stand (“Romero was the whole show. I do not think Brett saw any other bull-fighter”). In search of assertion, the reader could cross out background information unrelated to the performance at hand and be left with just a fistful of poor phrases.

Equally anemic as the Biographers are Hemingway’s “hard-shelled technicians,” who feel compelled to tell us when the bassoon is out of tune or take issue with the timpanist’s choice of mallets. The Technicians miss the forest for the trees and provide no insight beyond their own misplaced mastery of minutiae.

Finally, and most egregiously, music criticism can easily devolve into Judgment, wherein the all-seeing Critic has decided to point his infallible thumb to the heavens or to hell, with no evidence or explanation: the Critic has spoken. This, of course, is nonsense.

“The best music critics have never just held forth with judgment as if from on high,” Listen editorial consultant Bradley Bambarger wrote me after I approached him with this article’s thesis. “The critics who add something to the artistic equation tell a true story about a recording or a performance. That story has the ‘how,’ the color and atmosphere and connoisseur’s detail to evoke the music, to prick a reader’s ears through their eyes, in a way. The story also has the ‘why,’ providing the context of trends and history. This is the nuance that can still make criticism enlightening and relevant, that can make it cultural news. If a critic isn’t telling this kind of story, then what he or she is doing isn’t real arts criticism — it’s just slinging opinion.”

‘Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words? He thinks I don’t know the ten-dollar words. I know them all right. But there are older and simpler and better words, and those are the ones I use.’

— Ernest Hemingway

Critics should be writing for Brett, the smart observer new to the art but hungry to learn more. Brett knows the Romeros when she sees them, but she would be delighted to know why they are so great. She also recognizes fakers, and is eager to find out how they can be exposed (“the tricks other bull-fighters used...”). You can show Brett what to watch for, “what [it’s] all about,” explain the arc of a work to reveal “more something... with a definite end, and less of a spectacle with unexplained horrors,” the latter potentially being a new listener’s reaction to a Schoenberg masterwork.

To take ephemeral greatness in a performing art and quantify it in written or spoken expression is both a difficult task and a noble aspiration, and those who do it well ought to be admired and valued more than they currently are. My critical heroes include New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis, whose recent look back for that newspaper at (the now late) actor Dennis Hopper, “Madman Perhaps; Survivor, Definitely,” captured Hopper’s unnerving brilliance: “If the pleasure of his performance is tinged with discomfort, it’s because Mr. Hopper has apparently never been afraid of looking ridiculous — an important quality for performers.”

Music critic Paul Griffiths in 2002 miraculously quantified the audience’s unease at the premiere of John Adams’ On the Transmigration of Souls for the now defunct online magazine Andante: “One can understand why the New York Philharmonic should have sought, while the World Trade Center site was still being cleared, an opportunity to speak to the moment with music of the moment. But it was inevitable that any new composition would come both too late and too early. A year later, the moment has passed: shock and outrage, though not forgotten, have become the prelude to more considered anxieties.”

My favorite critic is boxing manager and color commentator Teddy Atlas, who susses out fighters’ weaknesses seconds after the opening bell and predicts knockouts rounds before they happen. His anatomy of a fight consistently reminds us that The Sweet Science, too, (like bullfighting) is a performing art. During the heavyweight main event of an ESPN Friday Night Fights broadcast in April, Atlas observed to play-by-play man Joe Tessitore: “Right now the man in control of everything as far as the rhythm goes — and the rhythm is everything — it’s Thompson. You know, Thompson is the ocean, Joe, and Beck is just a log: he’s being pulled in and out by the tide of Thompson.” After a pause, Atlas added: “I think the log, being Beck, is about to become driftwood.” Beck’s corner threw in the towel two rounds later.

Atlas, like Hemingway, locates a humble elegance in his keen imagery. And like all great critics, he makes us better students by teaching us how to think more critically. “She saw why she liked Romero’s cape-work and why she did not like the others.”

related...

-

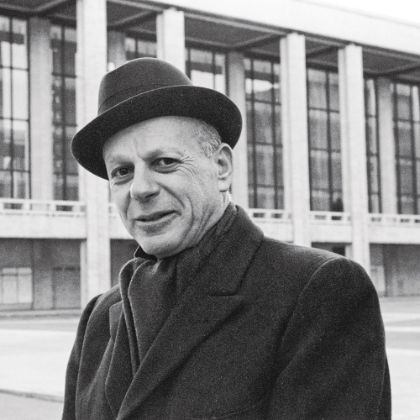

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine