The beautiful stoicism of Brahms’s Nänie defies absolute categories.

By Thomas May

You’d sometimes think Johannes Brahms had been canonized the patron saint of “absolute music” — music that’s supposed to be about nothing beyond its own domain. That old way of thinking dies hard, and it makes it all too easy to overlook the marvelous examples of “interdisciplinary” compositions that were an important part of Brahms’s output.

Actually, we have the musical party politics of the nineteenth century to thank for the supposedly rigid distinction between absolute and program music. The notion of dividing music into opposing camps is a habit that reflects aesthetic battles fought long ago, in which Brahms was cast as the champion of absolute music against the revolution proclaimed by Wagner, Liszt and their followers. But these kinds of oppositions are about as useful as splitting the world into “conservatives” versus “liberals.”

And Brahms’s creative imagination was far too rich and complex to fit so obligingly into that schematic pigeonhole. In fact, one of his most moving works is heavily programmatic beyond the usual business of illuminating a text: along with the poem by Friedrich Schiller that it sets to music, Nänie, Op. 82, composed for chorus and orchestra (and completed in 1881), weaves together inspiration from the visual arts. Brahms conceived it as a memorial to the painter Anselm Feuerbach (1829–1880), with whom he had had a troubled acquaintanceship. (The artist was too high-maintenance for the composer to succeed in his attempts at becoming his friend.) However frustrating Feuerbach was on a personal level, Brahms deeply admired his artistic values, sensing they were aiming for similar goals in their respective disciplines. Nänie provided a pretext for addressing this, and through it, the far more ambitious theme of what solace art can offer — against all the odds.

Nänie and a handful of other choral–orchestral works of similar dimensions are some of the loveliest gems in Brahms’s entire catalog. So why have they managed to slip through the cracks? Only the Alto Rhapsody and possibly Schicksalslied (“Song of Destiny”) are encountered with any frequency in the concert hall; Nänie remains a true rarity and connoisseur piece.

Perhaps that’s because it’s a hard piece to categorize. The much earlier A German Requiem, whose concluding movement (“Selig sind die Toten”) Nänie hauntingly echoes, is far more popular — and far easier to place within a tradition. To be sure, Brahms’s approach to the age-old liturgy was radical in its own right — he stitched together his own text of humanist commemoration from diverse biblical sources — but A German Requiem can still be readily positioned alongside more conventional sacred music that mourns the dead. Nänie, on the other hand, exists in a category of its own. Its title alludes to a classical song of grieving unfamiliar to modern listeners. (Nänie is the German version of the Latin naenia, which can also refer to the personified goddess of funeral songs.) It evokes a vanished ritual of poetic lamentation whose very obscurity underscores the work’s central image of transience.

Brahms composed his stand-alone choral–orchestral pieces during an era when secular choral music flourished among the public at large. Participating in choral societies provided a major outlet for a rapidly expanding middle-class demographic of music lovers. In fact, it was his work conducting exactly these sorts of societies that laid the foundation for Brahms’s career as a composer. In our time, as conductor and music scholar Leon Botstein notes, the diminishment of the prominent role once played by choral singing has had an ironic result: choral works like Nänie, which played a significant role in Brahms’s evolution as an artist, now make up the most neglected area of his legacy.

As a song of mourning, Nänie suggests links with the earlier German Requiem, but it also closely parallels Brahms’s mature orchestral compositions. With this piece he returned to a choral–orchestral format after a decade in which he had focused on instrumental music — including the first two symphonies and the Violin Concerto. Some commentators suggest Brahms approached the single-movement, freestanding choral work epitomized by Nänie as a way to channel his anxieties over competing with the choral symphony Beethoven had established decades earlier with his Ninth.

Brahms’s famous Beethoven complex is just one example of a theme that recurs throughout his career: the feeling of a past golden age of art overshadowing the decadent present. Brahms found an analogue in the work of Feuerbach, whom he first got to know in 1865. Like Brahms, Feuerbach was a lifelong bachelor. He came of age in Germany and Paris and spent much of his career in Italy developing a style of idealized neoclassicism that yearned for a romanticized, irretrievably distant past.

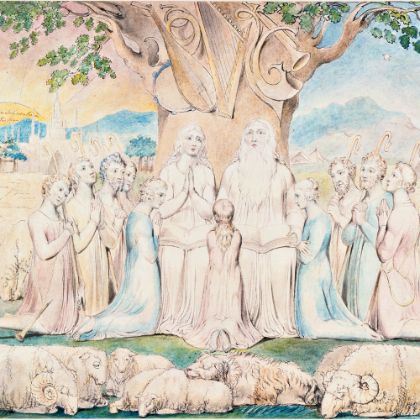

Brahms was especially moved by the subtle pathos in Feuerbach’s rendering of such mythological figures as Medea and Iphigenia. The composer’s abiding enthusiasm for the painter’s work isn’t surprising: Brahms clearly identified with Feuerbach’s sober aesthetic, classical influence, and lyrical discipline as an alternative to the flashy, attention-grabbing styles that were all the vogue in Vienna. “We live in a century, as far as the arts are concerned, that worships mediocrity,” declared Feuerbach, mirroring a conviction Brahms was also known to harbor. As far as Brahms was concerned, Feuerbach was struggling against the visual equivalent of Wagner’s “music of the future,” with all its empty promises. But Feuerbach’s attempt to conquer Vienna was a fiasco (there was a meltdown episode directed against Brahms, who had tried to help him). Disgusted, Feuerbach retreated to Italy for his final years, dying in 1880 at the age of fifty.

Brahms was deeply stirred by news of the painter’s premature death in Venice. And thoughts of memorial music had already been on his mind: a friend and patron had recently requested a composition that could one day be played at his funeral — but a piece without heavy religious overtones. Meanwhile, the death several years earlier of the introverted composer Hermann Goetz (1840–1876) was still felt by Brahms, who had known and admired him. All of this became part of a chain of associations about transience and what an artist leaves behind.

Goetz himself had made a setting of Nänie, and this may have brought Schiller’s poem (published in 1799) to Brahms’s attention — or, even more likely, made the enormously well-read composer eager, once the time was ripe, to work out his own musical reflections on the poem’s themes of youthful mortality, the destruction of beauty, and art’s consolation.

“Also Beauty must perish!” begins Schiller’s poem (or, in other translations, “Even the beautiful must perish”) — an imitation in German of the elegiac style of the ancient Greeks. Nänie rallies three mythological examples to illustrate the point, each of them underlining the relentless pattern of fate: Eurydice dying a second and final time, Adonis lacerated by the wild boar, and Achilles felled at the gates of Troy (all described through oblique allusions).

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Brahms’s Nänie is its tone of serene resignation, utterly devoid of sentimentality or melodramatic posturing. Lasting less than a quarter hour, Nänie deftly encompasses the varied strands of Schiller’s imagery within a classically balanced tripartite form (A–B–A). The endlessly spooling opening melody — of similar vintage to the Violin Concerto, and featuring some of Brahms’s most exquisite woodwind scoring — is set in the major, as is the middle section depicting the gods weeping. Brahms touches on the glowing, major-key pathos of late Mozart here, mingled with his own radiantly woven counterpoint.

But the message transcends the act of mourning the human condition, the “lacrimae rerum note,” as W.H. Auden once put it. The beautifully recomposed and telescoped recapitulation illustrates art’s power to “recall” and creatively transform. And where Schiller’s poem ends on a dark, “soundless” note of oblivion, Brahms sets for a second time the one hope held out by art: “Even to be a song of lament on the lips of a loved one is glorious.”

“Nänie”

By Friedrich Schiller

Also Beauty must perish! What gods and humanity conquers,

Moves not the armored breast of the Stygian Zeus.

Only once did love come to soften the Lord of the Shadows,

And at the threshold at last, sternly he took back his gift.

Nor can Aphrodite assuage the wounds of the youngster,

That in his delicate form the boar had savagely torn.

Nor can rescue the hero divine his undying mother,

When, at the Scaean gate now falling, his fate he fulfills.

But she ascends from the sea with all the daughters of Nereus,

And she raises a plaint here for her glorified son.

See now, the gods, they are weeping, the goddesses all weeping also,

That the beauteous must fade, that the most perfect one dies.

But to be a lament on the lips of the loved one is glorious,

For the prosaic goes toneless to Orcus below.

Photos: bpk, Berlin/Art Resource, NY

-

From Christemasse to Carole

The birth of Christmas in medieval England

Read More

By David Vernier -

The Next (Not-So-)Big Thing

New chamber orchestras are popping up all over America.

Read More

By Colin Eatock -

A Father's Lament

Finding solace in the sound of authentic sorrow

Read More

By Rev. Jake Bohstedt Morrill