The sound world and temperament of Henri Dutilleux

By Jason Victor Serinus

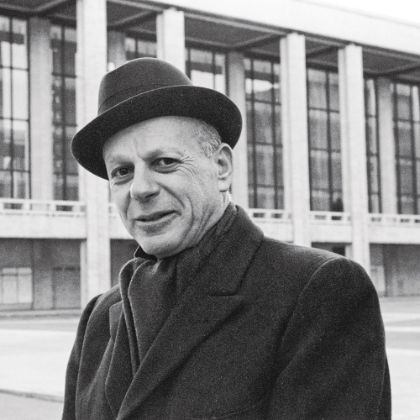

Had French composer Henri Dutilleux (1916–2013) lived just three more years, he would be alive today, in 2016, to celebrate the centennial of his birth. Yet in all his ninety-seven years Dutilleux composed approximately thirty mature works, plus nine other complete works that he disowned. Even if you consider the widespread popularity and frequent performance of his early works, especially his six short Au gré des ondes (At the Mercy of Waves) for piano, Dutilleux’s catalogue remains strikingly small. (By way of comparison, consider Franz Schubert’s output, who died at thirty-one!)

Despite his limited oeuvre, Dutilleux is nearly universally hailed as one of the last century’s supreme geniuses of French music. Often considered the rightful successor to Debussy, Ravel, and the other colorists who brought French music into the twentieth century, Dutilleux’s use of color, space, and timbral contrasts is so extraordinary, and so unmistakably his, that his language stands unique in the canon of classical music.

One of his most remarkable works is the cello concerto Tout un monde lointain… (A Whole Distant World), written for Mstislav Rostropovich in 1970. Although Rostropovich’s definitive 1974 recording with Serge Baudo and the Orchestre de Paris (EMI) has recently been re-released in a fine transfer, there is also a far more recent, marvelously recorded traversal by cellist Xavier Phillips with Ludovic Morlot and the Seattle Symphony (Seattle Symphony Media). About the cellist’s performance of this piece, Dutilleux himself said, “Xavier Phillips fully owns this work and evokes the very essence of its title — all a distant world.”

Whichever recording you audition, your attention will likely be drawn to the strange, opening haze that seems to usher you into a virtually indescribable phantasmagoric world. Dutilleux, an avid reader and extremely sensitive soul, was notably consumed by the poetry of Baudelaire. He chose the concerto’s title from Baudelaire’s poem “La chevelure,” which is part of the poet’s Les fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil). Ultimately, he wrote five movements, each paired with printed prefaces he drew from the collection.

The concerto’s first movement, “Enigme” (Enigma) seems to take its inspiration from “…Et dans cette nature étrange et symbolique…” (…And in this strange and symbolic nature…), a line from the twenty-seventh poem of the volume. Similarly, the fifth and final movement, “Hymne,” is prefaced by “Garde tes songes: Les sages n’ent ont pas d’aussi beaux que les fous!” (Guard your dreams: wise men do not have as beautiful ones as fools), which comes from another poem in the collection.

Each note, each chord is an event, which together with other notes creates a world like no other.

As Tout un monde lointain… proceeds, we find ourselves inexorably drawn into a strangely seductive, sometimes dangerous dream. Sounds are variously dark and dazzling, mysterious, and even savage. In conversation from Paris, Phillips said of the concerto, “I don’t know where I go, but it’s somewhere deeper than for other pieces. The music enters your mind in a very deep way, a bit like the poison the Dutilleux refers to in the fourth movement, ‘Miroirs.’

“The cello doesn’t play the typical role of the soloist in the classical sense. One commentator used the term ‘medium’ to signify the cello’s place in the middle of and around the orchestra. I find this image very interesting, and I cannot forget it. It is always with me when I play the piece. The experience is not only metaphysical, but also sometimes invokes the paranormal. It’s very strange, and it’s very, very special.”

As much as Dutilleux’s sound world found inspiration in the world of poetry, painting and dreams, its fantastic flights were frequently grounded in the harsh realities of the twentieth century. Dutilleux began writing the orchestral work, The Shadows of Time, in 1995, during the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II. As someone who endured the Nazi occupation of Paris, and spoke to some of his confidantes at length about the French Resistance that hid Jewish children from the Germans, he dedicated the work’s middle episode to “Anne Frank and to all innocent children of the world (1945–1995).” In The Shadow of Time’s final version, three boy sopranos join the orchestra to ask, “Pourquoi nous? Pourquoi l’étoile?” (Why us? Why the star?). Even amidst the shadows of suffering, Dutilleux affirmed the transformative power of the firmament and dreams.

Then there are the texts for his song cycles, which one might say respond to the world by divorcing themselves from reality. The cycle he wrote for soprano Dawn Upshaw, Correspondances, draws its title from a poem by Baudelaire that describes synesthesia. Its five texts alternate between the mystical poetry of Rilke and Mukherjee and several extremely potent letters: a deeply moving thank-you from Solzhenitsyn to Rostropovich and his wife, Galina Vishnevskaya, as the tenth anniversary of his exile approaches; and a composite of three letters from Van Gogh to his brother, Theo, in which the painter’s madness is clearly progressing.

Dutilleux wrote his final work, the song cycle Le temps l’horloge (Time and the Clock), for soprano Renée Fleming. The first songs set texts by Jean Tardieu, alongside whom Dutilleux worked for many years at Radio France. The third setting is of poetry by surrealist Robert Desnos, a member of the French resistance who died in the “model” Nazi concentration camp, Terezin (Theresienstadt), in 1945. The last song returns to Baudelaire via a famous poem that urges the necessity for a drunken approach to life in all its aspects.

For the world premiere, Dutilleux asked Fleming to recognize another member of the French Resistance by preceding the cycle with an orchestral arrangement of his first mature songs, Deux Sonnets de Jean Cassou. These songs honor Cassou, who lost his post with the Vichy government in 1940 as a result of his civil disobedience. The texts are drawn from two of thirty-three sonnets that Cassou composed during his subsequent imprisonment.

Although his music often stands witness to the dark world in which he found himself, nothing but generosity of spirit and a gregarious humility characterized Dutilleux the man. Oddly enough, these facets of his personality, combined with his obligations as the all-important head of music production for Radio France from 1945 to 1963 and professor of composition at the École Normale de Musique de Paris from 1961 to 1970, have been cited as reasons for the slow pace with which he composed. But Boston Symphony Orchestra artistic administrator Tony Fogg relates many of his encounters with Dutilleux draw a much clearer picture of the composer’s compositional process and his penchant for frequent revisions and postponements.

Fogg sat next to Dutilleux for the first performance of The Shadows of Time. “The piece finished with this rising figure going up and down and then this beat of tam-tams,” he explains. “At the conclusion, he just sat there. I turned to him and said, ‘Henri, you have to go take the bow.’ And he said, ‘But oh no, the toms, the toms, they’re not right.’

“I thought I had to get him up there [for a bow], which I did. Then came the intermission before the second half of the concert. He didn’t come back into the hall, and sat there during the whole second half of the concert into the night, trying to fix this detail at the ending of the piece.

“The next day, we did a slightly different version of the ending, and he said ‘No, no no no.’ Then he took the piece with him, and we re-programmed it months later in order to record it. When we got the piece back, he had added a final little flurry to the flurries at the end. With about four extra measures, he opened a whole different harmonic world, with a range of harmonies and colors that we had never seen or heard before. It was like being on a roller coaster and then getting to the highest point on the roller coast and being able to see a whole vista that you hadn’t experienced before.

“It’s what he knew was missing from the first version. He knew there was something that was not right about it, and he couldn’t accept it until he had worked out what it was. And then his wife, who was very close to him, had said to him that the ending was too sentimental. So the changes were partly in response to her as well.”

Dutilleux was hardly a lone wolf however, channeling his muse in private and insisting upon his sole creative instincts. Rather, he was an eminent collaborator, generous with his advice and eager to receive second opinions. This inclination of Dutilleux’s allowed him to foster scores of mutually rewarding professional partnerships, including one with the Music Director of the Seattle Symphony, Ludovic Morlot, who in August will complete a three-CD survey of Dutilleux’s complete works for orchestra. Morlot first met Dutilleux in Boston in 2001 when the composer attended a performance of the revision of The Shadows of Time.

“Dutilleux came from Paris for the rehearsals,” Morlot explained. “I sat next to him, scores in hand, and we chatted the whole time. He had traveled alone on that trip — without his wife — so we had breakfast, lunch and dinner together, chatting about music and many other things. We spoke much more about literature and art as a whole than music. And even though he had made the revisions, he’d keep on making small changes when he would hear something slightly different from what he had envisioned. He’d actually ask me about what I thought of one gong rather than the other, and I offered to try it. I saw his creativity unfolding in front of me.”

Each time Morlot went to Paris, he would visit Dutilleux in his apartment, talk about music, and have a martini. Usually he would call him, and Dutilleux would say that he was quite tired that day, and the visit couldn’t be very long.

“Four hours later, we were still chatting,” Morlot reports. “For me, as a young guy, it was a gift. It was incredible to be connecting with life in Paris from the 1920s and ’30s. To hear of his relationships with Honegger, Milhaud, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Picasso, and Diaghilev was something I would otherwise have put my hands on only by reading books. So I would just shut up and listen to him for hours.”

Renée Fleming, a long-time friend who knew the composer long before working with him on his final song cycle, remembers him fondly. “He was the most charming man,” she says. “And he was a tremendous flirt. He met my mother, and he had this extraordinary way of making every woman feel like she was the only woman in the world, and that is a lost art, of course.

“To see this man with the perfectly placed ascot, impeccably dressed, was a joy. Just walking up the stairs to his apartment and seeing the lifestyle he had, and how he lived, and his studio, and that piano, and knowing that he had to climb those stairs no matter what. And his love for his wife, and how he took care of her. He was just a wonderful person. Oh God, I miss him.”

Robert Levin, whose thirty-four-year friendship with Dutilleux began at Fountainbleu in 1979, when the two of them took over teaching composition for a failing Nadia Boulanger at her request, clearly adored the man as well:

“There’s very, very little doubt that Henri Dutilleux had a command of orchestral colors and sonorities that was and is utterly breathtaking, and places him within a very, very choice number of people who are among the greatest orchestrators of all time. When listening to a piece like Timbres, Espace, Mouvement, the way that he generates sonorous molecules, and the way they succeed one another — the glittering and radiance and at times stupefaction of chord progressions — is something which from my very first exposure to his music literally took my breath away. I find stupefying the succession of shimmering sounds that emerge in the Cello Concerto. When I first acquired the recording with Rostropovich, I had never heard anything that sounded so infallible in terms of its successions.”

Indeed, every note that Dutilleux ultimately left in place after his frequent rounds of revisions seems inevitable, as though his music could not be the same without it. Each note, each chord is an event, which together with other notes creates a world like no other. While Dutilleux’s music may initially seem strange, even forbidding, it in short order becomes so compelling, and so profoundly rewarding, that it’s hard to imagine the evolution of twentieth-century music without it. Only a composer with such a profound intellect and deep commitment to life could so thoroughly, originally and provocatively affirm our essential humanity and take us along on the furthest flights of imagination.

related...

-

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine