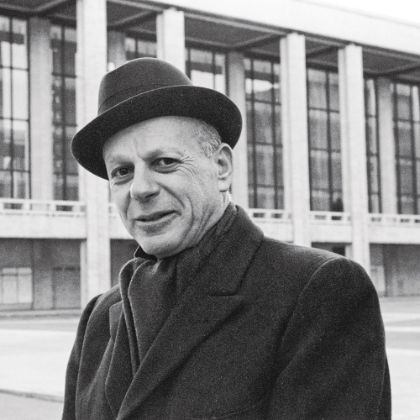

How the son of a Lithuanian immigrant discovered the American sound

By Colin Eatock

The critic–composer Virgil Thomson famously declared, “Every town in America has two things — a five-and-dime and a Boulanger pupil.” He was talking about the famous French music teacher Nadia Boulanger, whose school at Fontainebleau Palace, just outside Paris, became a mecca for young composers from the United States.

Boulanger was one of the defining forces of American music in the twentieth century. Many of her pupils went on to have impressive careers, but none more so than a twenty-one-year-old New Yorker who had started in music late but was determined to become a composer. His name was Aaron Copland.

Copland was the youngest of five children born into a family of Lithuanian Jewish immigrants. (Originally Kaplan, Aaron’s father anglicized the family name en route to America.) Copland Senior put down roots in Brooklyn, where he owned a small department store; the family lived upstairs and helped to run the business.

The composer later recalled, with a kind of ironic pride, that his neighborhood was a drab place, adding: “I am filled with mild wonder each time I realize that a musician was born on that street.” Yet his mother played the piano and sang, and some of his siblings also took an amateur interest in music.

Copland might also have become an amateur musician, but at fifteen he attended a concert by the famous pianist Ignacy Paderewski. He decided then and there to become a composer, and backed up his ambition with a decisive course of action. He studied piano, harmony and theory with purposeful intensity, and developed a keen interest in the modern music coming out of Europe.

When he heard through a friend that a new school for American composers was being established in France, he pooled his money and stepped forward as the first student to enroll at Fountainebleau in 1921. He had no doubt that he wanted to spend a year in Europe — but he had qualms about learning composition from a woman. Nobody, to his knowledge, had ever done this before.

Copland soon found his misgivings groundless, and developed a deep admiration for Boulanger, an organist who possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of music from Bach to Stravinsky. And the respect was mutual: she later recalled that she recognized his exceptional talent immediately. The young composer absorbed the exciting culture of Paris in the 1920s, the milieu in which such writers as Paul Bowles, Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway flourished.

One year in France became three, and Copland returned to the United States in 1924, well-versed in modern musical trends. Yet he returned to a nation whose musical life was very different from the America of today. There were, to be sure, a handful of American composers who had achieved a respectable level of success: Edward MacDowell, George Chadwick and Horatio Parker, among others. But the dream of writing a kind of classical music that was authentically American in style — in the same way that French music sounds French and German music sounds German — had proven elusive. America’s composers were too European in their sensibilities, and perhaps America itself wasn’t quite ready to embrace the idea.

Copland would become a leader in the generation that changed all that. But first, like every young artist, he wanted a big break — and the one he got couldn’t have been bigger. Boulanger helped make this happen: she introduced Copland to the esteemed Russian conductor Serge Koussevitzky, who was about to assume the direction of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He asked the young composer to write a large-scale work for organ and orchestra, which Boulanger could perform on an upcoming tour to America.

Boulanger also approached Walter Damrosch, conductor of the New York Symphony Orchestra, about the piece, and on January 25, 1925, Copland’s Symphony for Organ and Orchestra was premiered by the NYSO. A Boston performance under Koussevitzky followed in February. The three-movement composition, with its fluid harmonies and Stravinskian, irregular rhythms, received mixed reviews. Even Damrosch seemed uneasy about the work, famously remarking to his audience, “If a young man at the age of twenty-three can write a symphony like that, in five years he will be ready to commit murder.” (Copland later created an alternate version of the piece, without organ, calling it his Symphony No. 1.)

It could be argued that, like Dmitri Shostakovich, Copland had a ‘public style’ for his orchestral scores and a ‘personal style’ for chamber works.

Copland was now in the musical spotlight, and his goal of becoming a full-time composer of classical music (a profession that didn’t really exist in America at that time) lay within his grasp. Guggenheim fellowships and part-time teaching allowed him to live modestly in a New York apartment and work on his music. He banded together with other young composers — Roger Sessions, Roy Harris, Walter Piston and Virgil Thomson — who became collectively known as the “Commando Unit.” He became involved in the newly formed League of Composers. In his personal life he was openly homosexual, and he also took an interest in left-wing politics.

His association with Koussevitzky proved fruitful: the BSO’s flamboyant conductor led Copland’s jazzy and abrasive Piano Concerto, with the composer at the piano, in a 1927 concert that scandalized many Bostonians. And Copland’s star rose higher when, in 1929, his Dance Symphony won a prize in a music competition sponsored by RCA Victor.

With the arrival of the Great Depression, America’s musical landscape changed, and Copland adapted to the new circumstances. His left-leaning political convictions led him to question his own artistic values. And he came to feel that a new musical language — distinct from the brashly modernist idiom he had so successfully cultivated in the 1920s — was needed, in order to reach a wider audience. “I see no reason,” he wrote, “why composers any longer should write their music solely with the concert audience in mind. New listeners, such as the radio provides, may not be cultivated listeners, but at least they have few of the prejudices of the typical concert-goer.”

Several years after his sparsely pontillistic Piano Variations of 1930 (adapting the serial techniques of Arnold Schoenberg to his own purposes), Copland made a dramatic shift in style. His 1936 ballet El Salón México, inspired by folk melodies he heard on a trip, marks the beginning of this new aesthetic approach: transparent, melodic and unashamedly populist. More works in this vein followed, such as the ballets Billy The Kid, Rodeo, and Appalachian Spring, with its famous use of the Shaker hymn “Simple Gifts.” Copland also broadened his audience by composing for theatre, radio and film. His 1939 music for Of Mice and Men marked the beginning of his association with Hollywood.

Yet Copland was still, at heart, very much a composer for the concert hall. And when Koussevitzky approached him in 1944 to write a new symphony for the BSO, he began work on a piece that would marry his populist and classical inclinations. He worked slowly, well aware that the piece would be judged as the culmination of his career up to that point. “A forty-minute symphony is very different from a short work for a specific purpose,” he later told biographer Vivian Perlis. “It has to be planned very carefully and given enough time to evolve.

Copland’s Third Symphony is infused with a simplicity, dignity and energy that are unmistakable signatures of his mature style. Yet, significantly, the work contains no American folk tunes or jazzy passages. Copland does, however, quote himself in the final movement, drawing on an earlier piece, his Fanfare for the Common Man, written in 1942. Koussevitzky proudly dubbed it “the greatest American symphony.” Twenty-five years later, Leonard Bernstein declared Copland’s Third “an American monument, like the Washington Monument or the Lincoln Memorial.”

It is thanks to Copland’s popular orchestral works that he has become this nation’s foremost classical composer. And it is worth noting that he achieved this status as an unlikely candidate: a gay Jewish socialist. However, his orchestral successes tend to cast a shadow over his work for other musical media. Throughout his career, he maintained an ongoing interest in chamber music. His piano trio Vitebsk is occasionally performed, but other chamber works, such as his Sonata for Violin, his Piano Quartet, or his various pieces for string quartet, are heard only rarely. This music doesn’t have the direct, folksy quality of his most popular orchestral scores, and so it languishes in obscurity. (It could be argued that, like Dmitri Shostakovich, Copland had a “public style” for his orchestral scores and a “personal style” for chamber works.)

One large-scale work by Copland that still hasn’t won the popularity it deserves is The Tender Land, the only full-length opera he ever composed. Originally, this story of failed love in the rural Midwest was intended as an opera for television. But NBC rejected the score, and the work was staged by the New York City Opera in 1954. It received such bad reviews that Copland thought of discarding the piece. Perhaps the intimate nature of the story — lacking big, dramatic events — and an ending that leaves the audience hanging in uncertainty have hobbled the opera’s success. The problem certainly isn’t Copland’s emotionally engaged music, which makes the piece a crowning achievement of his populist style.

In the 1970s, Copland’s compositional output tapered off, and he spent more of his time conducting. In 1970 a young Leonard Slatkin, currently music director of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, met Copland when the composer was conducting his own music in Saint Louis. “He could be the most charming and delightful person,” Slatkin tells Listen. “I loved hearing about the early years from him. He was one of these people who championed his colleagues. He was amazing in that respect.”

Twenty-four years after Copland’s death in 1990, Slatkin believes his music has earned a solid place in history. “He embodied everything that was America in the twentieth century,” says the conductor, who is currently in the midst of a project to record all of Copland’s ballet scores with the DSO. He also believes Copland’s influence is still very much alive in the works of such American composers as John Adams and John Corigliano.

Today, Copland is world-famous for a handful of pieces — even as his other works gather dust on library shelves. But let’s be optimistic, and hope that the day will come when a fuller understanding of Copland will emerge. In our post-modern age, in which a multiplicity of styles is celebrated, we should remember that Copland was all about diversity — espousing an all-embracing approach that made him America’s most identifiably American composer.

related...

-

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine