Music in celebration of springtime

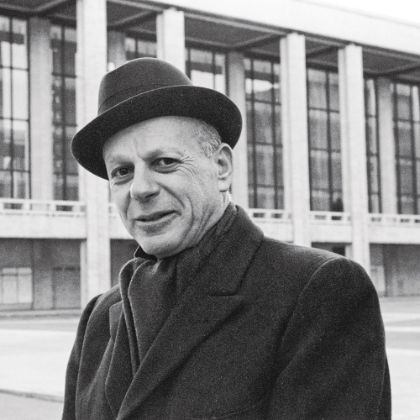

Jens F. Laurson

Alexander Pope tells us that hope springs eternal in the human breast, and if he isn’t referring to the eternal hope for spring, he really missed out on something. It’s just the thing after a long winter to find that spring has sprung, the grass has ’riz, and to wonder where the birdies is — as the anonymous bard so eloquently put it in “Spring In The Bronx.” Beethoven felt the same way.

So did Schumann, Mendelssohn, Stravinsky and just about every other composer who ever wielded his or her seasoned pen. They all wrote about spring in some way or other — famously or forgottenly, parenthetically or prominently. From Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck’s 1595 two-voice chanson Voicy du gay printemps l’heureux advenement1 to Benoit Mernier’s 2008 opera on Frank Wedekind’s play Frühlings Erwachen, the theme of spring has served as inspiration, picturesque expression and thematic link for composers.

Beethoven paid his celebrated tribute to nature in general and spring in particular in his Pastorale Symphony. Roughly twenty years before that he had already hinted at his feelings for spring when he penned his Op. 52, No. 4 Mailied (“Song of May”), a short, pretty song that anticipates his most famous lied, Adelaïde. It sounds particularly good in the voice of the twenty-five-year-young Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, who, at the time of his RIAS recording of it in 1951, was as old as the composer had been when he wrote it.2 Beethoven’s so-called “Spring” Sonata for Violin and Piano, Op. 24, by contrast, has no programmatic content and was nicknamed only later.

The most famous musical incarnations of spring are paths well traveled and oft-heard: Schumann’s First Symphony, the corresponding movements in Vivaldi’s Four Seasons or Haydn’s Jahreszeiten, Stravinsky’s Rite and Copland’s Appalachian Spring. Astor Piazzolla’s Las Cuatros Estaciones Portenas3 are now well known, and a popular companion to the Vivaldi. Their “Spring” isn’t just a rip-roaring affair; it also stands out as one of the few southern-hemispherical springs, from September to November.

One wonders what it says about Alexander Glazunov in particular or Russian springs in general that in his charming ballet The Seasons, Op. 67 — the work that gave Anna Pavlova her break — summer, fall and winter all get decent attention, while spring is skipped by with brief and subdued gaiety.4 Teasing spring out of Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons, Op. 37, can be done month-by-month, with March’s “Song of the Lark,” April’s “Snowdrop” (’tis Russia!) and “Starlit Nights” in May.5 Bach contemporary Christoph Graupner also offers a month-by-month cycle among his many keyboard works: his twelve suites titled Monthly Clavier Fruits include “Martius,” “Aprilis” and “Maius.” Because of their success, Graupner went on to compose a follow-up “Seasons” cycle, but only “Winter” (GWV 121) survives.6

Henri Sauguet’s “Seasons” is a little-known contribution to the symphony genre. Sauguet started out as a provincial organist, studied with Joseph Canteloube — who has a few spring references in his own Chants d’Auvergne7 — after the Great War, and got a gig writing for Ballets Russes. In the resulting work, La chatte, George Balanchine gave his debut. Sauguet did all that on the side, as an amateur composer who benefited from the advice of Milhaud, Debussy and Satie. Sauguet was drafted in World War II despite “incurable weakness” (a French precursor of “don’t ask, don’t tell”), from which he seemed to emerge with stoic confidence. In 1949 he wrote his Second, “Allegorical” (or “Seasonal”) Symphony, a grand two-hour tour of the seasons for large orchestra and mixed choir that sounds like a throwback to Debussy and D’Indy in the best sense.8

The lark brings to mind Haydn’s so-nicknamed String Quartet, Op. 64/5, and animals in general indicate spring in music where titles don’t spell it out.9 Schubert’s upstream-swimming Trout points likely, if not definitively, to spring. Respighi’s “Birds” from his Three Botticelli Pictures certainly do, and Frederick Delius tells us exactly when he heard his first cuckoo (namely, in a very calm spring).10 The opening movement of Gustav Mahler’s First Symphony is a cornucopia of spring sounds without the label. Full of birdcalls, it’s right in line with the goldfinches in Vivaldi’s Flute Concerto, Op. 10/3, “Il gardellino.”11 “Pan awakens,” the first movement of Mahler’s Third Symphony, is about “summer marching in,” which is a euphemism for all-out spring — and Mahler turned once more to spring with his drunkard from Das Lied von der Erde.

Even if the stereotype of gaiety and fairy music does the work of Felix Mendelssohn an injustice, he is the composer we could most easily imagine prancing about in flowery fields. His use of spring isn’t excessive, but it’s there, alright: The very pretty “Spring Song,” Op. 34/3 is one example, the six-part a cappella piece “The First Day of Spring,” Op. 48 another, and at least two further spring references can be found by dipping your ears into Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words. Song No. 6 from Book Five, Op. 62 is easy, because he also titled it “Spring Song.” Op. 19/5, “Leise zieht durch mein Gemüth,” is the other, on a Heinrich Heine poem, and exists also as a song (Op. 19a/5). Its most intriguing incarnation, however, is Aribert Reimann’s reconception, “Mendelssohn — ...or is it Death?” Scored for string quartet and soprano, Reimann lets the subtly sinister strings chirp with delicious ambiguity behind the hardly altered vocal part.12 13 14

Johann Ludwig Uhland’s poem Frühlingsglaube has proven a popular fountain of spring songs. Schubert, who never met a poem he didn’t put to music, created a setting that just needs the right singer to be very beautiful.15 Louis Spohr tried the same thing, but with less success and lesser interpreters having had a go at it. Franz Liszt took Schubert’s song and ran with it beautifully in one of his song transcriptions for piano.16 Among choral settings, it is Alexander von Zemlinsky who found Uhland’s poem an ideal way to elicit his late-Romantic orchestral-choral gorgeousness17 — a wonderful way to warm up to Zemlinsky’s music, if you don’t already know it. Christian Lahusen, the Argentine-born German World War I fighter pilot-cum-composer, used Uhland’s text, along with several other spring poems, for his “Spring Songs,” a part of his large, simply beautiful choral cycle Ein Schöpfungsgesang (“Song of Creation”).18

‘For a Norwegian, spring must have had that extra bit of importance. Little wonder, then, that Grieg should have actively engaged himself on that topic, often to famous effect.’

For a Norwegian, spring must have had that extra bit of importance. Little wonder, then, that Grieg should have actively engaged himself on that topic, often to famous effect. Spring — Våren in Norwegian — can be found in a great number of his opus numbers, but it’s often the same lovely work regurgitated in another form: for voice and piano (Op. 33/2), solo piano, piano two hands, orchestra (all Op. 34/2), and voice and orchestra (EG 177). The transcription Til våren (“To Spring”), Op. 41/6 is based on the song Op. 21/3.19 20 21 The famous lyric piece “To Spring,” Op. 43/6 is one of a kind, while the “Spring Dance” is an all-too-literal mistranslation of Springdans, which literally means “leaping dance” and might best be translated as “folkdance,” the Norwegian Springar. More romantic Norwegian spring incidences come from Christian Sinding’s short and effective piano piece “The Rustles of Spring” (Frühlingsrauschen), which helped the onetime Eastman School of Music professor (1921) to fame in his lifetime, if not in posterity.22

There are many other worthy spring-themed works — by the likes of Eben, Hindemith, Koechlin, Künneke, Ladmirault, Liapunov and Milhaud — that go unnamed here. But the following works deserve at least a nod for their gorgeousness: Ernest Bloch’s variously dancing, then ardent spring in Hiver-Printemps23; the reconstructed version of Debussy’s original Printemps for orchestra and chorus (rather than the standard version for orchestra, two pianos and no chorus by Henri Busser) that Emil de Cou concocted and recorded with the San Francisco Ballet Orchestra24; and Benjamin Britten’s rousing chorale “Spring Symphony,” Op. 44, with its very robust reawakening of everything in nature.25

Shortly after endeavoring to “collect” spring music for this article, I was invited to a Boulanger Piano Trio concert on the outskirts of Munich. Even amid special moments of Beethoven and Brahms, the definite highlight was the namesake-honoring encore D’un matin de printemps by Lili Boulanger. It was already on my list, but undiscovered. Now it came to life, and how! This superb miniature contains all the hints of budding modernity and lingering Debussy — in under five minutes.Lili Boulanger, the first woman to win the Prix de Rome, was as physically feeble as she was musically gifted. Few other composers achieved so much in so little time; she died at the age of twenty-four. Her famous older sister Nadia, teacher of a who’s who of twentieth-century composers and musicians, subdued her own composing urges because even if she was very mildly defensive about Lili’s output (“There are no technical novelties in Lili’s writings — she lived in an age when intellectual speculation had not yet arrived, but she was able to find the necessary elements for expressing her own very personal message”), she thought that her own talents as a composer did not hold up to the standards Lili had set. D’un matin de printemps, its moods as volatile as April weather, is hardly Lili’s most important work, but it is a perfect example of all that is magnificent about her compositions, regardless of which version one listens to: the one for colorful orchestra, violin and piano, piano trio, or the two-piano arrangement by Jean Françaix. Of all the above works, this has become the dearest to me while writing and listening to spring.26 27 28 29

From Atalanta in Calydon

By Algernon Charles Swinburne

When the hounds of spring are on winter’s traces,

The mother of months in meadow or plain

Fills the shadows and windy places

With lisp of leaves and ripple of rain;

And the brown bright nightingale amorous

Is half assuaged for Itylus,

For the Thracian ships and the foreign faces,

The tongueless vigil, and all the pain.

Come with bows bent and with emptying of quivers,

Maiden most perfect, lady of light,

With a noise of winds and many rivers,

With a clamour of waters, and with might;

Bind on thy sandals, O thou most fleet,

Over the splendour and speed of thy feet;

For the faint east quickens, the wan west shivers,

Round the feet of the day and the feet of the night.

Where shall we find her, how shall we sing to her,

Fold our hands round her knees, and cling?

O that man’s heart were as fire and could spring to her,

Fire, or the strength of the streams that spring!

For the stars and the winds are unto her

As raiment, as songs of the harp-player;

For the risen stars and the fallen cling to her,

And the southwest-wind and the west-wind sing.

For winter’s rains and ruins are over

And all the season of snows and sins;

The days dividing lover and lover

The light that loses, the night that wins;

And time remembered is grief forgotten,

And frosts are slain and flowers begotten,

And in green underwood and cover

Blossom by blossom the spring begins.

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Back to Bach

Pianist András Schiff revisits The Well-Tempered Clavier and other totems of J.S. Bach — on stage and on record.

Read More

By Bradley Bambarger