The mysterious and wonderful music of Henri Dutilleux

By Menon Dwarka

This Listen feature was published three years before the death of Henri Dutilleux (1916–2013). —Ed.

Sometime in the mid 1990s, I heard a radio broadcast of a work that to this day remains one of the most unusual, striking and beautiful pieces of music I have ever encountered. As luck would have it, I tuned in somewhere in the middle of the work, so like most of us who listen to classical radio, I tried to see if I could guess the composer before the announcer commented at the end of the piece. The first thing I noticed was the orchestration, which was scored for the novel combination of strings, percussion and cimbalom. I knew of only a handful of composers who had written for the cimbalom (a concert hammered-dulcimer), but the musical material didn’t reflect the style of those composers. Stravinsky used the cimbalom in his Ragtime, but this music didn’t have his syncopated rhythms and stuttering phrases. Instead, it was languid, fluid and strangely sensuous. What made it even more difficult to identify was that the composer seemed to be playing with the listener’s sense of time, which is to say that he was manipulating material with an awareness of how it might affect the listener’s perception of how time passes. The simple return to earlier material seemed more like a memory than a recapitulation, and the whole work seemed to hover in some dreamlike space where past, present and future coexist.

“That was Mystère de l’instant by Henri Dutilleux,” intoned the announcer.

A few days later, a trip to the library revealed that this haunting music was not penned by some new musical prodigy, but by a composer who at that time was more than seventy-five years old. The whole experience was quite bewildering, but most curious was not the work’s orchestration, its style, or even the age of the person who wrote it; I was perplexed by how a composer of this stature could remain invisible despite my best efforts to stay on top of what was going on in the contemporary music scene.

Now ninety-four, Henri Dutilleux’s life in music has been an extraordinary journey. Born in 1916 and the winner of the 1938 Prix de Rome, Dutilleux was poised to be one of France’s great composers, but like so many of his generation, his world was turned upside down by World War II, when he served — for a time — as an orderly. After a few years of piecing together various arranging, teaching and performing jobs, after the war Dutilleux began working at the RTF (French Radio and Television Broadcasting), where he served as head of music production from 1945 to 1963.

Dutilleux’s output during these years was admirable, but the demands of his position left him with far less time to write than some of his fellow composers had. This may have been fortuitous for Dutilleux, since the style of music he wrote as a younger man, a mix of Ravel and Roussel, was overshadowed by the work of Olivier Messiaen’s student Pierre Boulez, who championed twelve-tone music as the only viable way forward for any serious composer. And while Dutilleux may have fallen victim to changing fads of contemporary music, he may not have been entirely comfortable with his own compositional voice; he designated his Piano Sonata of 1948 as his opus one, distancing himself from his earlier, more derivative work. Overall, when compared with Boulez’s aggressively atonal music, Dutilleux’s post-impressionistic work broke relatively little ground as far as compositional technique was concerned. (Boulez’s dominance as the leader of the post-war avante-garde lasted primarily from the First Piano Sonata of 1946 to 1957’s Le Marteau sans maître.)

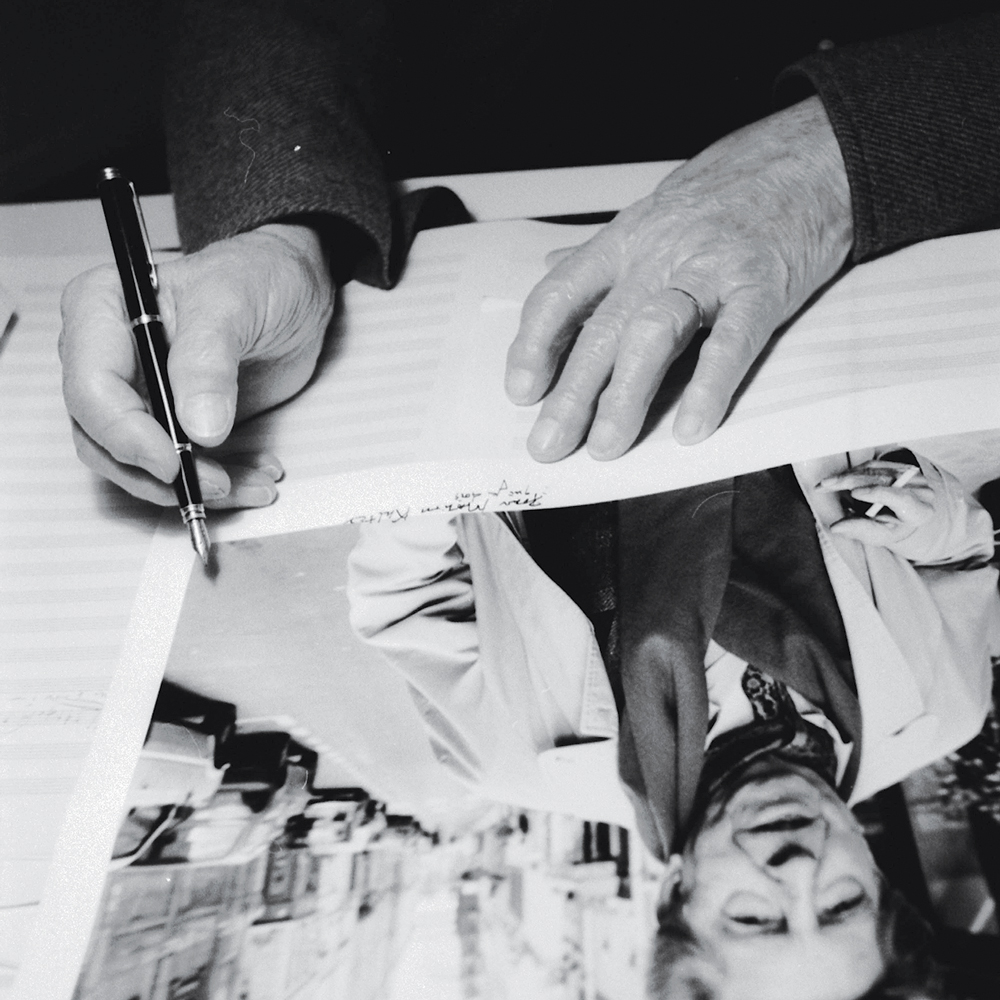

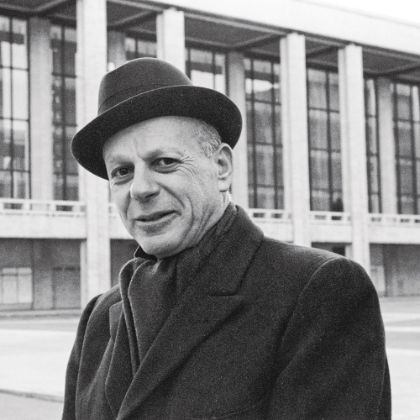

Obscured from view. Henri Dutilleux signing his portrait

Obscured from view. Henri Dutilleux signing his portrait

Out of fashion and with relatively few allies in France, help would come to Dutilleux from an unlikely source. The Boston Symphony Orchestra, under the direction of Alsatian conductor Charles Munch, had given several performances of Dutilleux’s First Symphony. The conductor, who was well known for his interpretation of modern French music, decided to award Dutilleux a commission to compose a second symphony. This work, subtitled “Le Double,” defined many of the aspects of Dutilleux’s mature style, most notably his use of presenting a musical theme in various guises. The orchestra is divided into two groups, one large and one small. Dutilleux’s music follows multiple versions of the same theme, sometimes with subtle variations, like the reflection of an image in a plane mirror, and sometimes more complexly, like the same image reflected in a fun-house mirror. This technique has its origins in the French tradition of centering a work around a cyclical theme, as in Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique or Debussy’s String Quartet. While composers from earlier periods tended to have a fixed “original” version of the theme that underwent progressive variations over the course of the work, in Dutilleux, there is no “original” version of the theme, but a conglomerate of intervals, contours and dynamic shapes with a tendency toward mutation rather than evolution and no hierarchical distinction above one another.

After the success of his Second Symphony, Dutilleux’s next work, Métaboles(1965), received repeated performances from another American orchestra — the Cleveland Orchestra, under the direction of George Szell. Following that success, a long list of performers, orchestras and foundations commissioned new works from Dutilleux: Mstislav Rostropovich (Tout un monde lointain), the Koussevitzky Foundation (Ainsi la nuit), Isaac Stern (L’arbre des songes), Paul Sacher (Mystère de l’instant) and others.

With the support of some of the biggest names in classical music, why would Dutilleux’s name still be hard to find in the 1990s? It might have something to do with his old rival, Pierre Boulez. In the second half of the twentieth century, Boulez quickly became one of the most sought-after conductors of his generation, accepting engagements with the New York Philharmonic and the BBC Symphony Orchestra in a self-imposed boycott of France. When he returned, he led the Ensemble InterContemporain and IRCAM, a research center for music and technology. None of these resources were put at the disposal of promoting Dutilleux’s music, which was, in an odd turn of events, often premiered in France by American and British orchestras on tour.

How then did Dutilleux’s music survive? The short answer is that his music is of exceptional quality, and that any musician or listener interested in music of this caliber cannot fail to take notice. Additionally, Dutilleux drew inspiration from artists outside the realm of music, with the twinkling harmonics of his string writing suggesting Van Gogh’s night skies, and his dreamlike narratives recalling Marcel Proust’s influence on the France of Dutilleux’s youth. Far less tangibly, anecdotal evidence throughout his life portrays Dutilleux as a man of exceptional kindness, generosity and good will, and performers, conductors and soloists have rallied to his side, giving his music the place it deserves among the very best of contemporary music scores. A listen to any of his works over the last fifty years — namely Ainsi la nuit, Sur le même accord (for violin) and Mystère de l’instant — are well worth the effort and, in some small way, would contribute to repositioning Dutilleux as one of the finest composers France has ever produced.

Photos: Lebrecht Music & Arts

related...

-

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine