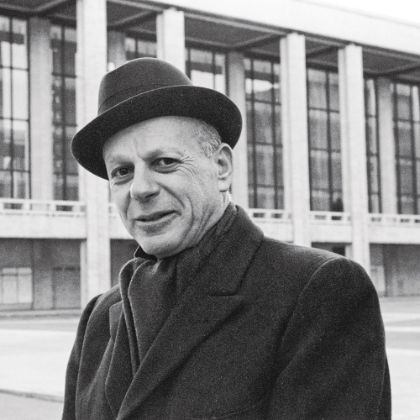

The Legacy of Prince

By Fred Chong Rutherford

The word “genius” is derived from “jinn,” a shape-changing spirit that can influence people to be good or evil. And to be a genius is something beyond raw intelligence: Ingrid Wickelgren, writing for Scientific American, claimed the defining characteristic of genius is “creative productivity.”

Mozart easily fits the multiple definitions of genius. His name remains so widely recognized in all cultures that you can omit the “Wolfgang Amadeus.” By the age of six, Mozart had already learned multiple instruments and was playing in public with his sister on a series of tours arranged by their father. In the thirty-two years since he first learned to play, Mozart created over six hundred compositions, a full lifetime of creative productivity for someone who only lived for thirty-five years. His life was one of music and poverty. His income was dependent on wealthy patrons and donations collected from performances. Copyright as we know it didn’t exist then, nor did the concept of recordings (or paying a musician playback royalties).

When we think of Prince, who recently passed away at the age of fifty-seven, genius may not be the first word to come to mind, but perhaps it should be. Prince Rogers Nelson was born to Mattie Della (a jazz singer) and John Lewis Nelson (a pianist and songwriter). Prince wrote his first song for the piano, “Funk Machine,” at the age of seven. By seventeen, he could play twenty-seven instruments and had recorded his first demo. By nineteen, he was signed to Warner with full control over the music produced in his studio. By the age of twenty-six, Prince was a household name. Each album showed range and a delightful sense of playfulness and soul. “Prince’s music will be remembered for its innovation and passion,” noted musician–composer Michael Aquino. “Making people all over the world dance to an apocalyptic tune [(“1999”)]? That’s a fine line you can’t fabricate in a studio.”

Before Prince’s death, the “Artist Formerly Known as” jokes had been passed around every late-night talk show and banal sitcom since the Nineties. Few people really understand why he exchanged his name for a symbol. Entertainment attorney John Kellogg explained in BBC News: “[Prince] felt the [record] contracts at the time were onerous and burdensome. He rebelled against that.” Changing his name to a symbol was a way to assert his artistic rights, free himself from contracts, and to release his own music under a new name — which he did.

It was easy to snicker. This strange, wealthy celebrity, claiming a symbol as a name, walking around with the word “slave” etched on his face. In those moments, we overlooked the significance of Prince’s race and indulged in the moments of schadenfreude that are so easy for famous people to provide. Sometimes, when we see real persecution, it becomes intolerable. In the best of circumstances, that intolerable feeling becomes a call to action, persecution subsides and fairness is restored. In the worst of circumstances, we explain away the intolerance by inventing our own persecution. We see ourselves as the only true victims. Inequity is reinforced, because in this delusion, we convince ourselves that the plain truth in front of our eyes is wrong.

How can we not see what it means when a black man etches “slave” on his face? How can we overlook the deep meaning of that act, or wonder at why an accomplished artist would do such a thing?

What mattered to Prince was his art. He shared it with the rest of us, but his art was his. No one would, or could, own him. No one would ever own him. At times, we conveniently obliterated Prince’s ethnicity when it allowed us to see him as a buffoon rather than a cultural champion. If we allow ourselves to truly see him, we witness how deep, personal, and ultimately human his fight was and prevent ourselves from shading our eyes from the contribution his music made to our culture.

Even if Prince had only been a composer, he would still be on par with the creative productivity of Mozart. But he was also a gifted multi-instrumentalist and a tremendous vocalist. Listen to “Purple Rain,” at the vocal range he occupies in the song; and if you ever saw it performed live, the highlight was witnessing Prince’s virtuosity first on piano and then guitar.

At the 2004 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony, Prince performed a singular guitar solo at the end of a star-studded performance of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” The joyful and incredulous faces of Tom Petty and Dhani Harrison during the performance revealed as much as the performance itself.

In his fifty-seven years of life, Prince released forty-seven albums of material. He famously recorded every concert he ever played, which numbered in the thousands. He wrote hit songs for other artists — including “Nothing Compares 2 U” for Sinead O’Connor, “Manic Monday” for The Bangles, and “How Come You Don’t Call Me” for fellow pianist Alicia Keys.

During his life, Mozart was renowned in Europe, yet died nearly destitute. At the time, his music was new, innovative, and not yet considered “classical” or part of the Western canon in the way we easily consider it now. He was a singular artist — something easy to see with the gift of distance and time. Prince was a musician’s musician, and a genius of similar caliber. He not only forged a legendary career in music, but forged a slew of precedents for artists and their rights — for everyone that comes after him. Like a genie, Prince changed his shape, yet was always recognizably Prince (even when his name was a symbol). Like Mozart, Prince’s influence will stretch beyond our own time. His music will become part of a new classical tradition, and his name will be remembered alongside other geniuses in the pantheon of artists.

related...

-

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine