When the Shoe Fits

Prokofiev’s Cinderella is much more than a charming retelling of the beloved fairy tale.

By Thomas May

After almost two decades in exile, Sergei Prokofiev had a multilayered mix of reasons for returning to the Soviet Union in 1936, including homesickness and a need to find a larger purpose for his work as a composer. And the Soviet authorities sweetened the allure by promising him special privileges, like a roomy Moscow apartment and permission to keep his precious blue Ford as private property.

But the timing couldn’t have been worse — not only for the composer, but for any Russian. The Stalinist terror, accompanied by its crackdown on independent thought and dissent, continued to accelerate. By the time reality reared its ugly head, it was too late: Prokofiev was back in the U.S.S.R. In the unforgettable phrase attributed to Shostakovich, Prokofiev landed “like a chicken in the soup.”

Perhaps as a result of the initial adversity he faced with Romeo and Juliet shortly after arriving, Prokofiev took a more cautious approach in conceiving of a follow-up ballet. He styled Cinderella in the manner of Tchaikovsky — to whom he dedicated the score — as “a classical ballet with variations, adagios, pas de deux and so forth.” He wrote that what he most desired to convey through the music was the underlying humanity of the characters: “the love of Cinderella and the Prince, the birth and development of this feeling, the obstacles in its way, and the realization of the dream at last.” The composer also remarked that he saw Cinderella “not only as a fairy-tale character, but also as a real person, feeling, experiencing and moving among us.” But in turning to an ultra-familiar story, Prokofiev could not only reliably connect with his audience, he could express his growing anxieties about the socialist dream.

On one level, Cinderella could spell out a kind of utopian allegory in which the class differences between prince and pauper are magically erased. (In a kind of reversal, Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty has come to be read by some as an allegory for Russia being put to sleep during the Communist era.) But instead of merely depicting a childlike never-never land, the score introduces complex layers of irony, parody, melancholy and even nightmare — a complexity reflected in the way real life interfered with Prokofiev’s creative plan. He began the score of Cinderella in 1940 and had sketched the first two of its three acts by the summer of 1941, when news of the German Wehrmacht’s invasion reached him on “a warm, sunny morning.” Relocated to safer surroundings far in the east along with other valued artists, Prokofiev set the ballet aside to answer the call for morale-boosting projects; the it wasn’t finished until 1944. He turned his attention to an opera on the more patriotically appropriate subject of War and Peace, whose vast score triggered a whole new series of run-ins with the apparatchiks.

It’s remarkable to realize that Cinderella was eventually completed in close proximity to such powerhouse scores as War and Peace, the Fifth Symphony, Ivan the Terrible and the so-called “War Sonatas” for piano. The ballet’s premiere, meanwhile, kept getting postponed, and the authorities even interfered by having the orchestration beefed up in spots where it was felt to be too light. The composer eventually prevailed and had the original restored, even garnering a Stalin Prize for Cinderella in 1946 — two years before he ran afoul of the cultural czars and was officially denounced for the crime of flirting with “decadent” individualism.

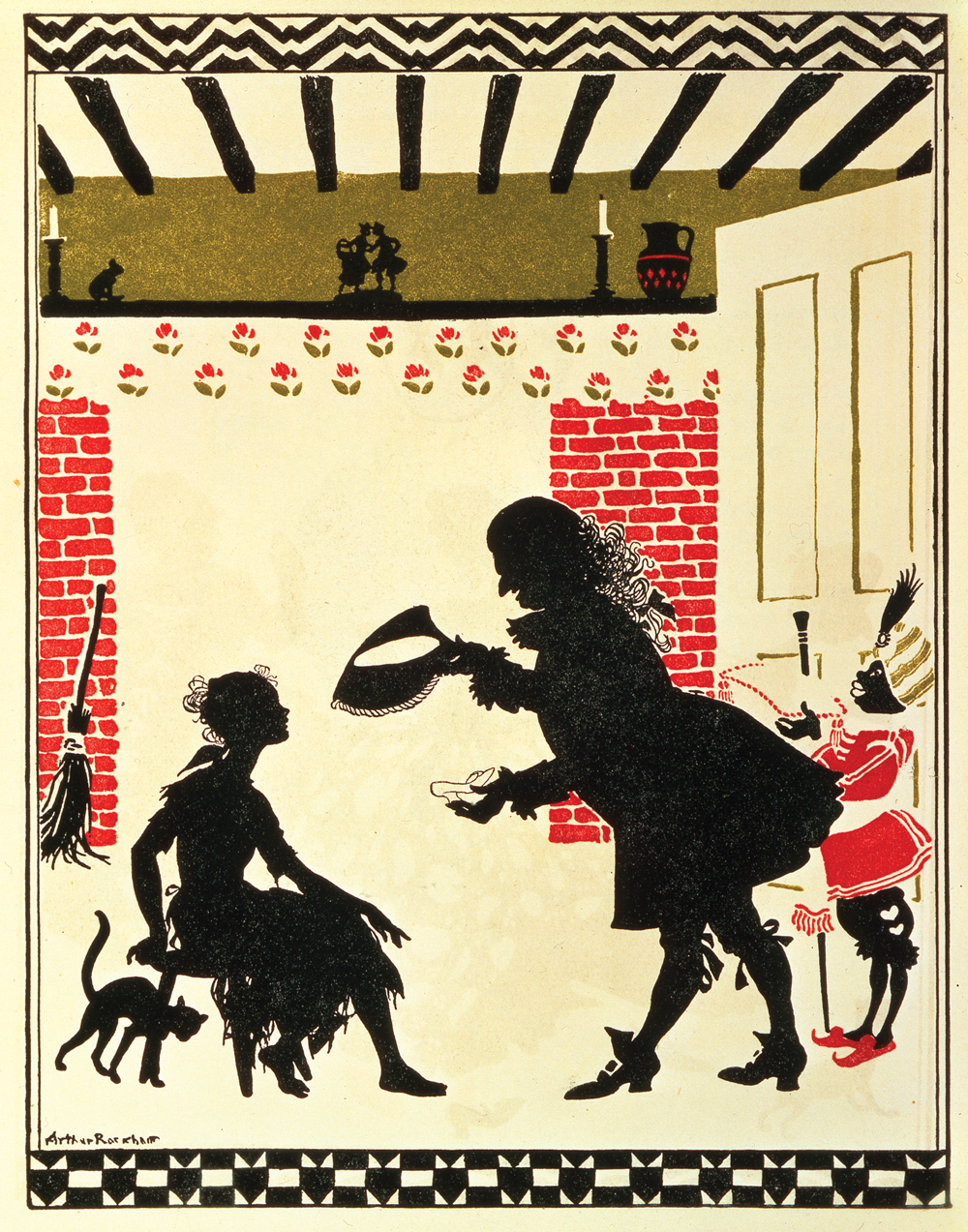

There are literally hundreds of variant versions of the Cinderella story, differentiated according to the use of smaller elements that folklore scholars refer to as motifs (the ball, the slipper, et cetera). Both the original Russian folk and Grimm Brothers’ variants emphasize a cruel, more violent slant, with mutilated feet and plucked-out eyes (the basis, incidentally, for Stephen Sondheim’s retelling in his musical Into the Woods). Prokofiev used a scenario by Nikolai Volkov that was based on the classic, gentler account in the Mother Goose Tales of Charles Perrault (1628–1703).

The ballet, which lasts about one hundred ten minutes without cuts, unfolds in a total of fifty brief episodes, many of which are named after classical ballet dances. A comic undertone is especially apparent in Prokofiev’s treatment of the wicked stepmother and the ugly stepsisters. Frederick Ashton’s acclaimed 1948 choreography for the Royal Ballet (available on DVD from Kultur) remains a thoroughly enjoyable introduction to the work and includes some hilariously exaggerated drag shtick. But beyond both the comedy and the pathos of the score, remarks New York Times dance critic Alastair Macaulay, Ashton’s “wealth of vocabulary and luxurious style expand the whole stage world,” opening up more of the ballet’s layers and “a new realm of form” to which the Fairy Godmother introduces Cinderella. When Nureyev staged Cinderella for the Paris Ballet in 1986, he found a fascinating metaphor for the ballet’s delicate dialectic of fantasy, dream and reality by setting it in Depression-era Hollywood, with the heroine being “discovered” by a film producer.

The score is a virtual compendium of Prokofiev’s varied, even contradictory styles; the grotesque, the “motoric,” the lyrical and the classical are all in balance with the modern. There’s much more here than Prokofiev the transparent “populist.” In contrast to the snarky “wrong-note” music of her tormentors, Cinderella’s musical portrayal conveys the ballet’s essential dualism, capturing both her soulful despair and her longing for a far-off happiness. The striking clang of colorful but mechanically repeated dissonances to mark midnight at the ball sounds a note of frenetic doom: time and reality insistently tick away. By the end of the ballet, notes Prokofiev expert Simon Morrison, Cinderella and the Prince face the challenge of “dislocation: they need to find each other. In the absence of paradise, their reunion has to serve as its own reward in time.”

Prokofiev structures pivotal moments of the score around his rewrites of that other iconic measure of time — the pulse of the waltz. A final “slow waltz” near the end of the third act propels the lovers into their private, transcendent world of happiness, “a nostalgic cosmos where love stays pure, unsullied by experience,” writes Morrison. “The tenuousness of this vision is denoted by its brevity.”

Photos: Art Resource, NY, Lebrecht Music & Arts

-

From Christemasse to Carole

The birth of Christmas in medieval England

Read More

By David Vernier -

The Next (Not-So-)Big Thing

New chamber orchestras are popping up all over America.

Read More

By Colin Eatock -

A Father's Lament

Finding solace in the sound of authentic sorrow

Read More

By Rev. Jake Bohstedt Morrill