The birth of Christmas in medieval England

By David Vernier

In June of the year 596, an expedition set out from Rome. This entourage of forty Benedictines, headed by a monk named Augustine, had been charged by Pope Gregory the Great with a daunting mission: to Christianize the Anglo-Saxons of southern England. King Æthelberht of Kent, whose wife was a Frankish Christian, had indicated a willingness to receive the pope’s emissary, and after a meeting to discern the worthiness and purity of Augustine’s intentions, the king allowed him and his party to set up shop in the nearby town of Canterbury.

Within a year, Æthelberht had joined the Christian fold. Soon more missionaries were sent from Rome, and together with Augustine (now anointed the first Archbishop of Canterbury) they began to not only convert thousands of the king’s subjects but also reform pagan temples to Christian use and foster the replacement of pagan customs with the celebration of Christian feasts and saints — particularly Christmas, one of the more important of the feasts. In fact, Canterbury in the final years of the sixth century set the stage for the rituals and customs much of the world still associates with Christmas — none more prominent and well-loved than its music, especially the carols, hymns and larger sacred works.

Of course, to most modern listeners, there’s nothing “Christmas-y” about the plainchant melodies that define the Christmas music of the early Middle Ages — after all, this was not popular music. It was intended solely to carry the words of the liturgy, whether in prayer, praise, thanksgiving, recalling a biblical event or iterating fundamental beliefs. Nevertheless, the chant repertoire particular to the Christmas season, which includes many special services and daily Offices and is celebrated from Advent through Epiphany, was vast and distinguished, and some of its melodies were later incorporated into modern works, including some of the carols and hymns we sing today. The fact that most of these melodies may be unfamiliar — and their text in Latin — takes nothing away from their particular ethereal beauty and profundity. They exalt the Virgin Mary, proclaim the birth of the Christ child, honor the visit of the Magi and recount the messianic prophecies of the Old Testament.

Let’s Start at the Very Beginning

Anyone curious to hear what this early Christmas music sounded like can find many first-rate, historically informed recorded performances, headlined by such recordings as Anonymous 4’s On Yoolis Night (Harmonia Mundi) and the Orlando Consort’s Medieval Christmas (Harmonia Mundi France).

Both of these exemplary programs confront the stark beauty and liturgical practicality of music designed purely to effect meaningful worship. Anonymous 4’s program — a collection of plainchant, songs, motets and carols from the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries — joins in praise of the “spotless rose,” the undefiled virgin who bore the Christ, and celebrates the many themes and symbols of Christmas that came to dominate all subsequent poetic and musical accounts of the Christmas story. Both recordings attempt to show the varied styles that developed from the early plainchant, from the beginnings of polyphony to its more sophisticated forms. The Orlando Consort’s program goes further, organizing the selections according to the themes of the texts, providing an overview of important categories of medieval Christmas music: Prophecy, New Year’s Day, The Carol, Narrative Motets, Noel.

A Rose By Any Other Name

No subject related to Christmas gets more attention than the adoration of the Virgin Mary. According to Anonymous 4’s Susan Hellauer, “Nowhere was her cult stronger than in the British Isles.” Hellauer observes that so much of medieval English song and poetry is devoted to Mary, the incarnation and the virgin birth that “it sometimes seems as if it were the English who gave form and substance to the celebration of Christmas.”

Not surprisingly, there exists an enormous body of Marian songs, hymns, antiphons and motets not only in English manuscripts but in virtually every part of the Christian world, from Italy to Scandinavia, and an accordingly impressive number of fine recordings devoted to the subject. The texts proclaim not only the name Maria, but the various symbolic representations of Mary: the Spotless Rose, the Rose of Heaven, the Star of the Sea, the Queen of Heaven. One of the best-known Marian songs is the fifteenth-century English carol “Ther is no rose of swych vertu” (There is no rose of such virtue). This beautiful song can be heard in various contexts on many recordings, but Anonymous 4’s version on the above-mentioned On Yoolis Night, set in its original two parts (with an added, improvised third), is among the best. The early-music group Virelai also offers a lovely rendition — for solo voice, lute and harp — on its aptly titled recording Ther is no Rose (Veritas). The disc features a generous program of early-to-late vocal and instrumental Renaissance Christmas music, including plainchant, a song by Hildegard of Bingen and several early English carols.

Bridge Work

The transition from plainchant and monophonic (single-voice) songs to two or more parts began around the end of the ninth century, aided by the invention of music notation. The American early-music vocal ensemble Pomerium offers a recording that serves as a nice bridge from medieval chant to the more complex forms composed by Praetorius, Josquin, Byrd, Lassus and Ockeghem. On Creator of the Stars (Archiv), the group performs an early chant and then follows it with a later, polyphonic work based on the original chant melody and text. The repertoire includes several of the most important and well-known Christmas texts and tunes of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, from “In dulci jubilo” and “Resonet in laudibus” to “Quem vidistis pastores” and “Alma redemptoris mater.”

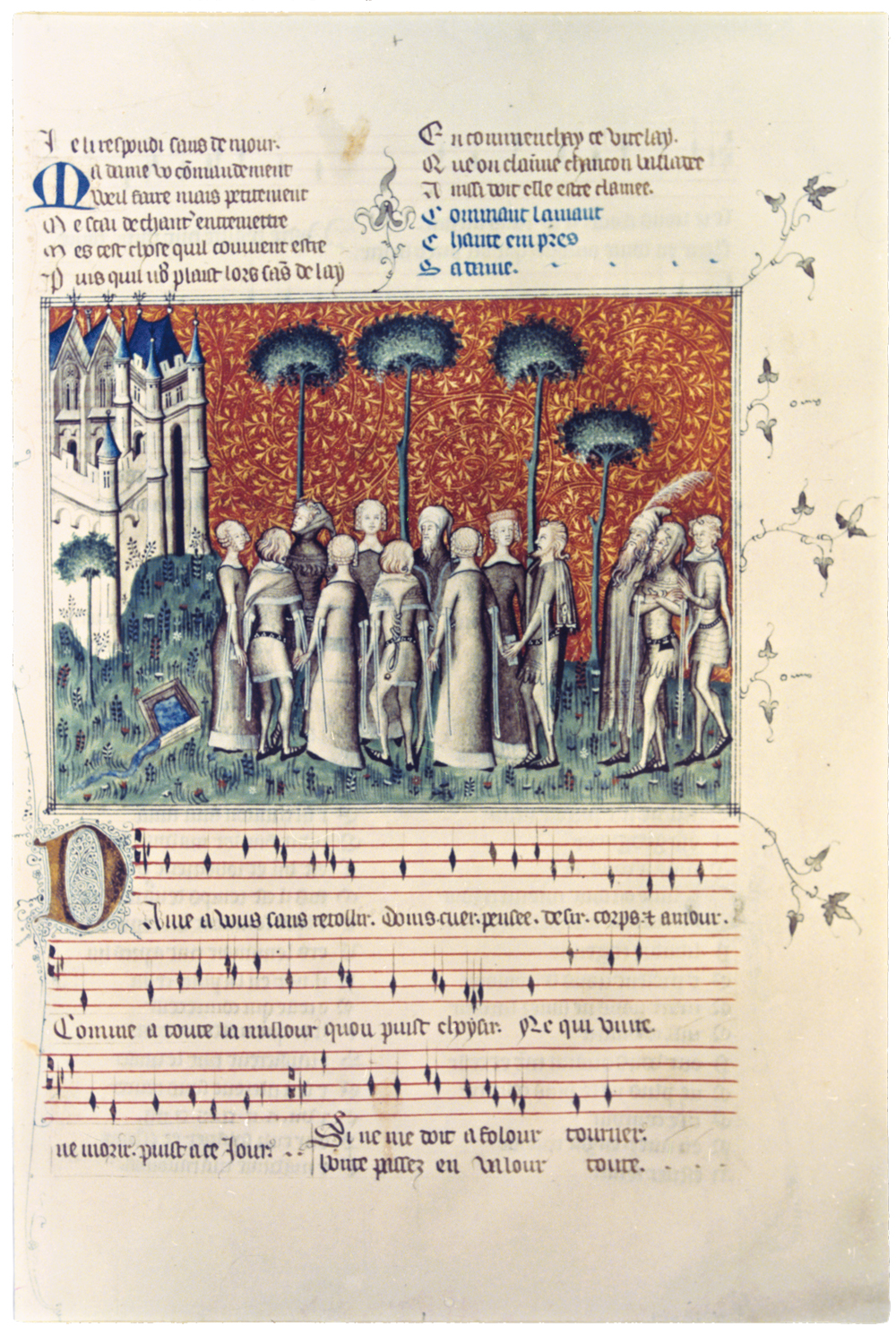

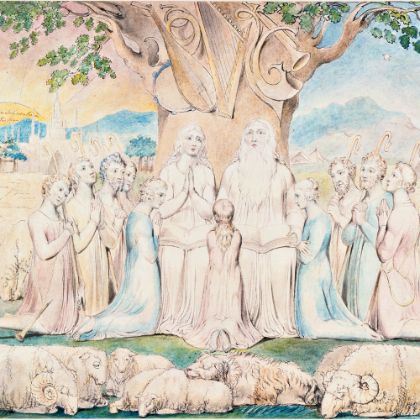

Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300–1377), Christmas Carol Dance, Manuscript illumination.

Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300–1377), Christmas Carol Dance, Manuscript illumination.

Mark It on the Calendar

Since the biblical gospels are not at all helpful in establishing the date of Christ’s birth, someone else had to do it; otherwise no one would be able to celebrate the event, which, along with Easter, gets the most attention on the church calendar. Volumes have been written and many arguments offered for how and why December 25 was chosen, or how unlikely the choice is, and how, owing to the foibles of various calendars and customs, the event should have occurred in, say, March, or May, or August (or shouldn’t be celebrated at all — “only sinners celebrate birthdays,” say some). Nevertheless, the selection of December 25 was probably based in part on the pagan winter festivals that already existed on that day (the ancient solar feast Natalis Invicti or the notorious Roman feast Saturnalia, which ended its weeklong revels around that time) and the church’s adoption of those festivals to get said pagans to join its team. December 25 is also nine months after the spring equinox (March 25 on the Roman calendar) and its accompanying pagan celebration of fertility; the modern church celebrates the Feast of the Annunciation on March 25.

However it happened, once the time of year was officially determined (probably sometime in the fourth century), the course of Christmas music history was set. Not only did the “bleak mid-winter” become one of the more vivid and affecting images of the season, but a whole body of songs, hymns and carols began to capitalize on the dramatic possibilities of cold, snow and wintertime activities and necessities. The shepherds in the fields, the journey of Mary and Joseph, the stark rudeness of the stable, the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes in the manger, the brilliance of the stars — all took on a more compelling aspect in the context of a cold and dark winter.

‘A whole body of songs, hymns and carols capitalized on the dramatic possibilities of cold, snow and wintertime activities and necessities.’

Carols were especially good at conveying these many moods — elation, wonder, apprehension, reverence — and their texts, written in the local vernacular, told compelling stories. The carol, from the French carole, was originally a type of dance performed in a circle. The music was characterized by a refrain sung before and after each verse — and often there were many, many verses. Carols were composed and sung for all sorts of occasions and were not specifically tied to Christmas. Today the term is almost exclusively applied to Christmas music — and many of the pieces we call carols are technically hymns or songs.

You could fill a very large room with recordings of Christmas carols — and those are just the better ones. One reason is the sheer number of tunes and texts; another is the variety of ways these songs have been composed, altered, revised, arranged and rearranged over the centuries. The first true carols appeared in Europe around the thirteenth century; by the fifteenth, England had its own impressive body of carol repertoire. Among the better choices of recordings that feature these early carols are the compilation by the Taverner Consort titled Carol Album 2 (EMI); the Waverly Consort’s A Renaissance Christmas Celebration (Sony); the Martin Best Ensemble’s Thys Yool; the Tallis Scholars’ Christmas with the Tallis Scholars (Gimell), which also includes Christmas hymns (chant) and a Mass from Salisbury; The Sixteen’s Christus Natus Est/An Early English Christmas (Coro); and, not to be missed, the York Waits’ Old Christmas Return’d (Saydisc), an irresistibly delightful celebration.

And They Say Nothing’s Sacred

By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, English composers such as William Byrd, Thomas Tallis and John Taverner were creating great polyphonic sacred works celebrating Christmas — Magnificats, Masses and motets that often were based on original medieval plainchant melodies. A new recording by Stile Antico, Puer natus est — Tudor Music for Advent and Christmas (Harmonia Mundi), highlights several magnificent examples of this repertoire, including Tallis’ compositional marvel “Missa Puer natus est” and Robert White’s Magnificat, a masterpiece among a host of other contenders. Another superb but likely-to-be-overlooked recording is the twenty-year-old Elizabethan Christmas Anthems (Amon Ra), featuring works by Byrd, Orlando Gibbons, Thomas Tomkins and John Amner. The performances by Red Byrd and the Rose Consort of Viols are excellent, and there’s some interesting instrumental music here as well.

What’s Old Is New

Though we leave the story of Christmas music here — at a very vibrant and vital moment in its history — it should be noted that three recordings clearly make the connection between the old and the more contemporary. The Baltimore Consort’s Bright Day Star (Dorian) juxtaposes some of the early carols with their counterparts in the New World, specifically from Appalachia. The performances are first-rate and the music is infectious. Paul Hillier’s Theatre of Voices brings a similar sensibility to Carols from the Old and New Worlds (Harmonia Mundi), which offers everything from early American tunes to Charles Ives and Jean Sibelius, joined by traditional English and European carols. And finally, Anonymous 4 joins the very recent with the very old in its Wolcum Yule (Harmonia Mundi), placing traditional English, Scottish and Irish carols alongside pieces by Benjamin Britten, Peter Maxwell Davies and Richard Rodney Bennett.

Photos: Erich Lessing, Art Resource, NY

-

The Next (Not-So-)Big Thing

New chamber orchestras are popping up all over America.

Read More

By Colin Eatock -

A Father's Lament

Finding solace in the sound of authentic sorrow

Read More

By Rev. Jake Bohstedt Morrill