Jimi Hendrix played the viola. And so do I.

By Helen Campbell

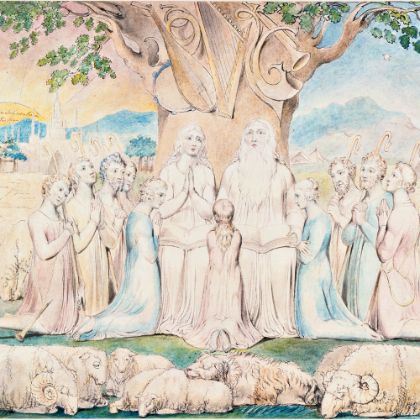

Cartoons by Christine Juneau

Years before he thrilled his fans destroying guitars, Jimi Hendrix was a geek. A single fact confirms this: he played the viola. Biographers either know nothing about it, or dismiss it as an embarrassing detail. We do know that he started in fourth grade and played in his public-school orchestra. Thereafter, the record is silent until his teen years, when he acquired a broken five-dollar guitar. At that point, a legend was born. Or so his biographers insist.

But let’s backtrack: why the viola? Nine-year-old boys don’t request such an untrendy instrument — and someone like Jimi would certainly have asked for a sax or a trumpet. What happened that day in his music class had to be simply the luck of the draw. Jimi, most likely, was stuck at the back of the line behind dozens of boys and got handed the last unclaimed instrument case. He probably toted it sullenly home — taking care to avoid the assemblage of punks on the corner — and waited to open it up. But something about the viola apparently grabbed him in that instant — most likely the fact that he could strum it in transverse position, guitar-style, as he’d done with a broom. It turned out that he liked the viola. And this part of his legend begs for recognition.

I too was a geek, but my route to the instrument wasn’t as quirky as Jimi’s. In fact, it fit the usual pattern. I was a passable violin student, who, fretting that I wouldn’t find an orchestral job, made a switch to the larger and heavier viola. The move, on its face, made good sense: I was certain I’d outshine most other viola players and triple my earning potential. Great idea, said my violin teacher, his hand raised in high-five position. You’ll never regret your decision.

But I did when I first heard the viola jokes.

To better assess if these jokes are a thigh-thumping hoot, the reader might need a few facts — for instance, that the string-playing world has castes. In symphonic music, violins furnish the melody; cellos, the heartbeat; and basses, the harmonic bedrock. Violas have no such significant function. Their primary role is “supportive,” which means they fill in or double the harmony. Their seating arrangement confirms this accessory role: they’re squeezed between cellos on one side and woodwinds on the other, and play with their instruments facing away from the audience, rendering them almost inaudible — except during waltzes, when they play the pah-pah that follows the oom.

It’s hard for this group to maintain self-respect. We know our orchestral colleagues perceive us as failed violinists and musical surplus. Our instrument has few defenders, and even composers malign it. Wagner once wrote, “The viola is commonly... played by infirm violinists, or by decrepit players of wind instruments who happen to have been acquainted with a string instrument once upon a time.” Hence, violists are prone to self-loathing and partial to Scotch.

Yet few people fathom the technical challenges facing violists. The instrument breaks you. From the standpoint of physics, its very construction is flawed: the viola’s strings are too long for its sound box, producing a thin, nasal tone in its upper registers and a muffled, bumpy sound in its lower ones. Its weight and proportions defy human handling, and worse, it subverts any effort to force a clear note from its bowels. Violists, in short, wrestle wolverines. It isn’t surprising that the names of the instrument’s most famous players reflect the grappling and choking required to play it: Trampler, Tertis, Fuchs, Bashmet.

And wielding this stubborn contraption is hard on the body. Soft-tissue injuries — in joints, nerves and tendons — result from the player’s repetitive motions and kyphotic playing posture. Kindhearted instrument makers have tried redesigning the viola ergonomically — but no one is anxious to buy one. These modern “violas” are shaped like amoebas, provoking convulsions of laughter from other musicians. Violists would rather remain as they are, walking wounded, than suffer more ill-treatment.

So what do I tell those who tell me viola jokes? It’s tempting to punch them, or show them my wrist brace and X-rays, or ask them why bagpipes and theremins and bassoons are spared the abuse people gleefully heap on violas.

But I don’t. Instead, I tell them about Jimi. “Hendrix? Played the viola?” they reflexively snort. “Get the hell out!”

Yet it’s true. And Jimi knew something that took me a long time to learn: taming this instrument calls for tenacity, sureness and — most of all — joints of titanium. He wisely moved on to a less brutal, more beloved ax. But no one who’s actually played the viola would mock those who do. Jimi would surely defend us.

-

From Christemasse to Carole

The birth of Christmas in medieval England

Read More

By David Vernier -

The Next (Not-So-)Big Thing

New chamber orchestras are popping up all over America.

Read More

By Colin Eatock -

A Father's Lament

Finding solace in the sound of authentic sorrow

Read More

By Rev. Jake Bohstedt Morrill