How dance music found its stylized peak in the Baroque — and how Bach can make us dance today

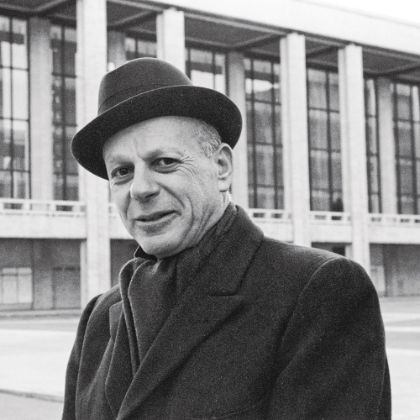

By Jens F. Laurson

Overture

The Ouvertüre, which must be of gallant character, deserves more praise than there is room here to describe. — Johann Mattheson, Der vollkommene Capellmeister (1739)1

Dance has always been accompanied by music. It took centuries for the two art forms to separate and for dance-independent music to emerge. Even then, dance still very much continued to inform music, as it does to this day. But in the Baroque era in particular, dance music evolved into a pinnacle of craft and stylization — no better represented than by the partitas, suites and overtures of Johann Sebastian Bach. Even now, hundreds of years after music and dance have parted, musicians are rediscovering the deep-seated and joyous dance at the center of Bach. This is a selective account of that story.

Allemande

The Allemanda . . . is an earnest, ornamented and finely crafted harmony that conveys the expression of contentedness or of a cheerful temperament delighting in good order and serenity.

Dance and music appear to have been inseparable until the fourteenth century, at the tail end of the medieval era, when the first specialists came along to teach only one or the other. In the medieval era, a refined style of courtly dancing, appropriated from common dances, had emerged, and with it proper names for each dance.

Outside the battlements of nobility, however, dancing activities were not yet codified affairs. When epidemics raged, it was not unusual for outbreaks of hysterical mass dance-madness to occur. Known as danses macabres, these dancing manias were meant to ward off death, but could last for days and themselves lead to death from exhaustion — a curious case of self-predicting choreography. Medieval Italians, meanwhile, danced the tarantella whenever they stepped on a bigger spider; it supposedly cured the fatigue that such a bite induced.

Dance rapidly turned from an unregulated, convulsive free-for-all into an art form during the early Renaissance. With symmetry being paramount in dancing, dance music consisted of symmetric elements whose structure was audibly reinforced for the dancer; eventually, distinct rhythmic patterns were also adapted by music not necessarily intended to be danced to. Although not every Renaissance composer adhered to strict proportions as closely as William Byrd, with his pavans and galliards2, metric organization with recurring accents did provide the basis for a stricter sense of structure in the coming Baroque era.

Scherzi musicali, ballettos and madrigals are all examples of dance-based musical forms that came about during the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras. Arcangelo Corelli’s Sonate di camera and Sonate di chiesa3 are dance-based, and so is John Dowland’s use of the pavan (a slow processional dance) in “Lachrimae or Saeven Teares.”4 Claudio Monteverdi’s opera L’Orfeo, dance-like throughout, ends in a grand moresca — the kind of sinuous, exotic dance that Salome was always depicted as performing for Herod.5 His Zefiro torna, e di soavi accenti (“The Zephyr returns and with soothing sounds . . . ”), with its positively dancing basso ostinato, bounds and leaps palpably.6 And those sixteenth-century hoofers who knew how to dance a galliard could conceivably shake a leg to “God Save the Queen” or “The Star Spangled Banner,” both audibly based on its pattern.

Courante

The passion or emotion in which a Courante should be performed is sweet hope. For there is something heartfelt, something yearning and also something pleasing in this melody: the many elements that form hope.

With the beginning of the Baroque era in the seventeenth century, dance music for dancing and dance music for listening further separated. Instruments like the lute and the harpsichord were generally used for the latter, while strings — like the Vingt-quatre Violons du Roy, the orchestra of the French royal court — were meant to play for ballets and balls. But dance remained influential even in those pieces designed purely for concert or drawing-room presentation. Long after it had fallen out of practical dance use, the allemande continued as an omnipresent and increasingly complex component of Baroque music.

German composers introduced dance movements in the French and Italian style into their music in the late seventeenth century. Many orchestral suites of the time contain dance-form movements. In Georg Philip Telemann’s suites — he wrote six hundred of them — some movements are even named after characters of dance, like Les Combattants or Harlequinade.7 But stylized dance music was not limited to keyboard suites and other purely instrumental music. Bach couldn’t help but sneak dance into a few of his cantatas. In a bass aria from Himmelskönig, sei willkommen, BWV 1828, Jesus is driven before the throne of his father to the strains of the gavotte from Bach’s fourth French Suite, BWV 814.9 And he has an undeniable spring in his step.

The influence of dance on music continued unabated into the Classical era; Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert all wrote dance-hall music, and of course dance music spilled back into their “serious” works. The list — which includes Smetana, the Valses of Ravel and Sibelius, and everyone named Strauss — continues on, but it is Bach who is most intriguing, in particular the stylized forms of Bach in dance — and how modern dance reclaims these elements by using Bach.

Sarabande

It has to express no other emotion but that of veneration.... But when performing it on the clavier or the lute, one can use more freedom, ornaments, or secretly make variations of it, which the French call Doubles.

The principal form of stylized dance in Baroque music is the French keyboard suite from about 1650; at its core are the allemande, courante, sarabande and, a little later, the gigue. These suites were imported to German lands by the likes of Johann Lorenz (in Copenhagen), Heinrich Scheidemann (Hamburg) and above all “Roman Imperial Chamber Organist” Johann Jakob Froberger (Vienna), who had studied in Paris and learned from masters like Jacques Champion de Chambonnières. His Partita No. 2 in D minor, FbWV 602, from the Libro Secondo (1649), is considered the earliest surviving suite with a gigue at the end. It’s hard not to bop along with its rustic rhythm the way Bob van Asperen plays it in his magnificent Froberger survey.10

Girolamo Frescobaldi, another Froberger teacher, augmented the suite with the corrente (courante) and ciaccona (chaconne). To this were added aria and variations of Italian origin and eventually French ballet dances like the menuett, bourrée, gavotte, passepied and passacaille. The result was the suite of “mixed style” mastered by Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer11, Johann Ludwig Krebs, Johann Joachim Quantz and of course Johann Sebastian Bach. Variations and chorale partitas, too, could be dance-based, as is the (apocryphal but fascinating) Bach Sarabande con Partite in C Major, BWV 99012. At the end of the piece, its composer — whoever it is — places an Allemanda, Courante, Aria Variata and Giguetta.

'Bach flooded his music with a sense of humor.'

Studies of these dance forms, their origins and tempos, are increasingly taken into account by today’s performers, whether part of the “historically informed” crowd or not. The time of sewing machine Baroque recordings — Vivaldi notoriously suffered — has long ended, and with each new recording the element of dance becomes more overt. Compare, for example, the early recording of Bach’s Partitas by András Schiff (Decca, proper and dour) to his remake a quarter century later (ECM, infused with compelling motion).13

If you’ve always tapped a foot along with Bach, swaying your hips is going to be next. The 2010 recording of his Orchestral Suites by Concerto Cologne14 is exemplary for a host of smart, historically informed performances that bring out both the subtle and explicit underlying dance. The Concerto Cologne’s use of the lower “French” Baroque pitch common in Bach’s Weimar and Cöthen works underscores the relaxed, flexible buoyancy of the music. And you sense the specific dance character in the fearfully fast minuet and passepied, but also the grave processional of the ceremonial sarabande.

Gavotte

Its effect is truly a jubilating joy.... Its beats are even of number, but it is not in four-four time but one that consists of two half beats. A leaping nature is well the characteristic of these Gavottes, and not a walking one.

There are many ways to express the vivacious element in Bach. Charles Curtis, veteran avant-gardist, extensive La Monte Young collaborator and longtime principal cellist of Hamburg’s North German Radio Symphony Orchestra, has released an extraordinarily charming CD titled Bach: An Imaginary Dance.15 Rather than getting near Bach’s dance character by means of archaeological work, he aims at the joyous roots of the music by spelling out a dance of his own imagination — assisted, in three cello suites, by Indian tabla hand drums and a small continuo organ. On paper that’s an odd combination; in practice it’s oddly addictive — like a sophisticated version of humming along, but, unlike Glenn Gould, very much in tune.

“Playing the Bach Suites, I don’t necessarily hum along,” Curtis tells me, “but I hear all this stuff that is not in the text. I just get carried away with the dance movements and yield to a kind of abandon. You start thinking of the power of the rhythms as dance rhythms. But during a performance, all of that is in the background. I wanted to see what happens if you make all of those goings-on audible.”

In doing so, he revived the lightheartedness we’ve forgotten to approach Bach’s music with. Bach flooded his music with a sense of humor. “Not ha-ha funny, with good-humoredness,” Curtis says. The involuntary, bopping smile that came to Curtis’s face while working on the Suites with organist Anthony Burr and tablaist Naren Budhakar comes across — broadly — on record. Curtis says that smile continued through the unaccompanied sections, too, which he was eager to include for variety’s sake: “The sarabande and its very dance-like, ceremonial quality is more chordal, which makes the organ seem superfluous. And the rhythms are much gentler, which doesn’t particularly suit vigorous drumming. And one needs a little relief from the combo. You don’t want to be hearing it all the time.”

Bourrée

The Bourrée is a melody more flowing, gliding, even and connected than the Gavotte. Its true character is based on complacency and a compliant manner, but at the same time it has bestowed upon it a somewhat insouciant or tranquil touch, a little careless, leisurely — but without displeasing.

Charles Curtis is not the only one inspired by the sense of movement inherent in Bach’s stylized dance forms. If dance, turned into abstraction, became music through Bach and his colleagues, the process is now working in reverse: the music of Bach is becoming the impetus for modern dance. As the music once took on motion, so it now gives motion: Bach as a rechargeable battery of dance — and with amazing battery life.

The starting shot of the Bach dancing renaissance seems to have been George Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco (1941), set to the Concerto in D minor for Two Violins, BWV 1043. Countless others have followed. There is the all-male drag group Les Ballet Trockadero’s costume-laden spoof Go for Barocco; William Forsythe’s meta-ballet Artifact — half speech-theater, half Kraftwerk aesthetic; and Rodrigo Pederneiras and his Grupo Corpo–created Bach, a mix of Las Fura dels baus, National Aerobics Championship video and Wendy Carlos. The Goldberg Variations alone have attracted dozens of choreographers: Marie Chouinard with her darkly mechanical-sexual Body Remix — Goldberg Variations; Susan Jaffe’s classical duet Royenne; eponymous improvised solo efforts by Mark Haim, Steve Paxton and a very lyrical choreography by Gregory Dawson. Plots are either absent or superimposed, as if the element of abstraction in the music carried over into the choreography.

Menuet

It has no particular sentiment other than that of reasonable gaiety. Anyone who wants to have a Menuet for the clavier need only open the manuals of Kuhnau, Handel, Graupner, etc., where, in order to find out the difference of the three menuet types, he may ask himself whether the chosen melody of the type is suitable for dancing or for singing. And the first glance will answer him in the negative.

One ballet using Bach’s music stands out amid the others, and that is Multiplicity / Forms of Silence and Emptiness. Created by Nacho Duato for Weimar’s 1999 European Capital of Culture celebration, it’s about Bach’s life, set entirely to Bach’s music, and the very embodiment of what Charles Curtis describes going on in his head during Bach: “When we listen to these pieces and observe them, we’re not actually dancing. But in some cognitive way we’re dancing vicariously. And we’re participating in it; we’re projecting ourselves into the dance and are participating in some of that ecstatic experience. There’s sort of a sympathetic vibration in Bach’s music which has a reciprocal effect on the listener.”

Multiplicity/Forms spells out that idea with amazing physical vivaciousness. Eschewing live music, Duato used excerpts from specific recordings in his collection at the time to create an hour-and-a-half-long soundtrack. With performances by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Anner Bylsma, Davitt Moroney, Sigiswald Kuijken, Andrew Manze, Gustav Leonhardt, Ton Koopman, Jordi Savall, André Isoir, Joseph Payne and Reinhard Goebel — Bach aficionados will nod knowingly — Multiplicity/Forms is on excellent musical footing. Glenn Gould’s Aria from his 1981 Goldberg Variations, used for the prologue, also provides the epilogue (and enough time to fumble for a handkerchief). The dancers solemnly, rhythmically walk off into eternity, bringing the ballet full circle. And in a way, dance and Bach, too, are brought full circle.

Gigue

The common, or English, Gigues are distinguished by a heated and fleeting fervor, an anger that wears off quickly.16 However, the Loure, or slow and dotted Gigues, show a pride, pompous nature, which is why it is so popular in Spain.8 The Canarie must contain great swiftness and desire but at the same time sound a little simple. The Welsh Gigue... for fiddling positively forcing us to utmost speed and volatility, but often in a fluent, not impetuous manner: like the smoothly gliding current of a river.13, 16

related...

-

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine