THE OPERA HOUSE

A Russian short story

by Ben Finane

ON 1 May as he tried to secure his baggage about him while being propelled off the plane in St. Petersburg by a stout babushka, Veniamin Vasilievich was pleased to note that his left ear had stopped bleeding. He dug a finger in to be sure, and, retrieving nothing but dry red flakes of paprika, felt very much relieved indeed.

The irritation in the ear of Veniamin Vasilievich traveled upward into his eyes as he emerged into the smoke-filled arrival hall of the St. Petersburg airport. At the bar — for there was one — all manner of passengers drank vodka from plastic cups and smoked cigarettes and the occasional cigar, ashing into the cups when they became empty. Stumbling over valises, Veniamin Vasilievich made his way through the thick haze to the escalator, descended, and was deposited into the back of a crowd, remaining there for an interminable period to see the Department of Passport Control. He could not determine which line progressed to which booth, or if any of the lines led anywhere at all, and so, hesitant to commit, Veniamin Vasilievich seemed always to remain au fond, until, without detection of progress, he found himself suddenly at the front, speaking to the official in the Department of Passport Control: a man short of stature, somewhat pock-marked, with a bald forehead and wrinkled cheeks, and a complexion of the kind known as sanguine.

“State your name,” said the official, peering over his spectacles.

“Veniamin Vasilievich,” replied Veniamin Vasilievich.

“Why have you come to St. Petersburg?” the official inquired.

“I have come to see the opening of Mariinsky II, the new two-thousand seat, twenty-two-billion-ruble state-of-the-art opera house that marks a new era for St. Petersburg’s legendary Mariinsky Theatre,” recited Veniamin Vasilievich.

The official took notes with a short pencil, nodding vigorously in approval.

“The opening of the new opera house further marks the completion of the Mariinsky cultural complex in St. Petersburg’s historic Theatre Square,” Veniamin Vasilievich continued, “and provides the legendary Russian organization with even greater artistic possibilities.” Veniamin Vasilievich exhaled.

“You are not a journalist?” said the official, picking his nose.

“No,” lied Veniamin Vasilievich, feeling parched and dizzy.

The official stamped the passport with a grand flourish in the Russian tradition, and pointed to the exit.

Leaving the Department of Passport Control, Veniamin Vasilievich paced aimlessly and anxiously at the airport entrance, un roi sans divertissement, looking for familiar faces until a man in a black suit with a black visor cap approached him.

“Veniamin Vasilievich?”

“I am he,” replied Veniamin Vasilievich.

“We wait for you, but you do not come,” said the driver, for so he was. “You must now travel with Europeans. They come three o’clock. You wait.” The driver escorted him into the bright sun, and then into a dark van, wherein Veniamin Vasilievich gathered his luggage underneath him and, fatigue from his flight smothering him like a woolen overcoat, went at once to sleep without dreaming, waking only briefly to espy the Monument to the Heroic Defenders of Leningrad float past the window, guns at the ready, flag raised.

• • •

Many hours later, Veniamin Vasilievich found himself seated with Italian, German, Japanese, British, Spanish, French, American and Russian journalists in a Georgian restaurant of high regard, his plate attended to and refilled by waitresses who communicated with the kitchen staff and one another through security headsets. The charismatic yet halting buzz of English as a second language darted around his ears (“We are coming here — since five years.” “While roads is breaking, the government are playing with us like privates!”) Excellent breads, cheeses, vegetables, meat and fish continued to arrive until Veniamin Vasilievich felt he must leave immediately — before dessert and coffee — or remain forever. He awkwardly excused himself, stumbling out the door onto the streets of St. Petersburg.

The light was failing but there were few shadows as the buildings were short and there were no trees. Keeping the water on his right, Veniamin Vasilievich pulled the collar of his overcoat close, for the evening chill had arrived, and made his way excitedly toward the site of the new opera house, stopping in the middle of the street to consult his map several times en route. Turning a bend, Veniamin Vasilievich found the Mariinsky II suddenly in front of him, unassuming in stone and glass: boxy, yet pastorally bridged over the Kryukov Canal to the original, more ornate Mariinsky, now Mariinsky I. (He knew that just beyond, out of sight, lay the Mariinsky III, a small, fine wooden ship of a concert hall with its wooden panel constructions. Built before Mariinsky II, it was now relegated to third in the matryoshka order.) Veniamin Vasilievich squinted and peered into the windows of Mariinsky II, but the house had not yet officially opened, and there was neither light nor a clue as to what awaited in its interior. He shrugged, turned, and walked along the Kryukov back to the hotel.

II

It must be known that Maestro Valery Abisalovich Gergiev, the great conductor and Artistic and General Director of the Mariinsky, expresses himself chiefly by relating whatever weighs on his mind au moment: projects, repertoire, performances, recordings, the importance of serving youth, the greatness of Russia — all in one continuous theme, shining an unpredictable spotlight on haphazard details. If a question is posed, Maestro has a habit of never answering directly — or if he does, of leaning forward, brow furrowed, hand placed tragically on the forehead rubbing the temples, and rumbling pleasantly directly into his free hand in a soothing manner.

Sitting at the top of a set of stairs in Mariinsky II and clutching a small complimentary bottle of fizzy water, Veniamin Vasilievich was glad that Maestro had been given a microphone to amplify his murmurs but was vaguely anxious that he had also been given the floor without fear of interruptions or follow-up questions. But then Maestro began to speak, and Veniamin Vasilievich scribbled madly in his notebook, all the while trying to piece the parts together into a greater whole.

“…Up to seven, eight performances a day,” said Maestro, speaking to the conceivable workload of the three combined halls.

“Surely this is madness,” thought Veniamin Vasilievich, his brain dizzy at the arithmetic and audience-building that would be required.

“People tell me students are our biggest audience now,” Maestro continued. “For those who are now five, seven years old, a huge opportunity to experience for the first time in their lives the miracle of classical music.”

“There could be no argument there,” Veniamin Vasilievich considered. “Bravo, Maestro.”

“Domingo came in ninety-two, February,” said Maestro, “to Russia. The country was two months old…. The record label is my own answer to what I think recording industry should do today. Don’t kill project if you think it’s going to lose five dollars — but it is the best project.... I know Shostakovich Five is a better-known symphony than Twelve. But Twelve is a good symphony. Fourteen is a good Symphony.”

Veniamin Vasilievich shifted his weight. Now Maestro was recounting the 2003 fire in the Mariinsky Theatre’s warehouse. “…There were two and a half walls left. It felt like Stalingrad. It was so painful. But I started to think, instead of warehouse, opera house.”

“Here is a fine slogan,” thought Veniamin Vasilievich.

“I called Toyota....” Maestro continued. “I much prefer to play with a known than with a totally unknown. I find it a big risk, maybe too big a risk for me....”

“A-ha,” thought Veniamin Vasilievich. “Here is Mariinsky III. We are getting close.”

“I was saying ‘yes’ to everything,” said Maestro, his eyes drifting to the window and the cloudless skies beyond it.

“ ‘Can we go up?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Can we go another ten meters?’ ‘Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes.’ Moved from two thousand, fifteen hundred, twelve hundred seats. So it can be grand.... Always with the family focus.”

“Still Mariinsky III. And yes I said yes I will Yes,” thought Veniamin Vasilievich, smiling.

“The Russian tsars were very quick.” Maestro was building to a close. “And by the way, they were very smart. They built culture like Medicis. I am very grateful to Alexander the Second.... Russia is seen as a country that thinks, but maybe not deep enough. I want to say that every country makes mistakes. But fortunately every country makes good things, thanks God, Russia included.”

• • •

Guards sprinted through the opera house foyer with semiautomatic weapons and German Shepherds. Their camouflage pants were ineffective against the Iranian onyx with LED–back-lighting that covered the walls. “Listen to me, Veniamin Vasilievich,” said a diminutive Russian journalist tugging at the elbow of Veniamin Vasilievich, who had started with alarm at the animals’ passing. “You cannot be too careful about security in Russia.”

Swarovski hung from the ceiling above, light fairly glinting off the guards as they tromped their way out. In the hall itself, more Swarovski dripped from the top of the Tsar’s Box (its actual title — old traditions are not so easily discarded), which cut mercilessly through two rings of the upper level. “You cannot tell, Veniamin Vasilievich,” the tour guide and likely former KGB man told him, “but crystal is actually supported by heavy cable. Do you see?” Veniamin Vasilievich squinted at the wires above the crystals. “One thousand kilograms they can take. Strong like bear.”

Two Asian men, scissors and box cutters moving at speed, were installing a long, thin strip of carpet at a break in the orchestra section halfway up the hall. As a replica of the original Mariinsky curtain lowered, Veniamin Vasilievich caught sight of a painter at work backstage, turning a once gleaming white panel black.

III

At a barked command from an offstage chinovnik, the crowd stood as a single animal. Veniamin Vasilievich stood as well, thinking that the national anthem was forthcoming. Instead, it was Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin.

“I should have foreseen this,” thought Veniamin Vasilievich, remembering yesterday’s newspaper article wherein the President had awarded Maestro the recently revived Stalin–era Hero of Labor medal; recalling the running of the German Shepherds from that morning; noting the official seal on the diminutive podium; and only now noticing in his periphery the goons who lined the walls of the hall, some still wearing their ineffective camouflage, looking everywhere but onstage.

The President, for so he was, stood no taller than five and a half feet and assumed the podium with legs apart and his center of gravity between them, as though he had just dismounted from his steed. He delivered a short speech of firm support, praising the Mariinsky as a flagship of Russian culture while noting that Russia now demanded cultural amelioration beyond Moscow and St. Petersburg. The President then strode deliberately down the steps of the stage and into the orchestra section, offering not even a cursory glance toward the Tsar’s Box but instead endeavoring to sit among the people (on the newly installed strip of carpet). He shook hands, embraced women (and would have kissed babies had there been any present) and made his way along the self-same strip of carpet the workers had laid hours earlier to take his seat.

For Veniamin Vasilievich, the two and half hours of the opening-night gala performance — presented sans entracte — swam by delightfully. He nodded approvingly at the acoustics and the sightlines and was beguiled by the shifting stage — maximized to great effect to introduce one dance or aria even as another rolled to its exit. He marveled at the bold and unapologetic Russianness of Maestro Valery Abisalovich Gergiev’s program, which opened with Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev’s “The Montagues and the Capulets” and drove through Igor Fydorovich Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring (with choreography by both Vaslav Nijinsky and Sasha Waltz), then on to George Balanchine’s Jewels and ballerina Diana Vishneva dancing Alberto Alanso’s choreography to Carmen’s “Habanera.” He tittered at pianist Denis Leonidovich Matsuev’s channeling of Chico Marx in Grigory Romanovich Ginzburg’s Figaro Fantasia from Rossini’s Il baribere di Siviglia.

“How did that Steinway get onstage?” wondered the French Canadian seated next to him. Veniamin Vasilievich could only shrug happily.

This is to say nothing of the blazing fiddles of Yuri Abromovich Bashmet and Leonidas Kavakos, of living legend Plácido Domingo, who reminded the ladies in their furs and the men in their smokings that he remained a tenor, offering Siegmund’s “Winterstürme.” To say nothing of the sensuous Anna Yuryevna Netrebko, who tried on Verdi’s Lady Macbeth, gave a taste of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta and participated in a gleefully cartoonish arms race of a “Là ci darem la mano” from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Don Giovanni that had Veniamin Vasilievich laughing as he had at simpler jokes as a younger man. When he thought there could be no more, there appeared the great Olga Vladimirovna Borodina gently serenading him with “Mon Coeur s’ouvre à ta voix” from Saint-Saëns’s Samson et Dalila. It was the end of a night to remember for Veniamin Vasilievich, and for Maestro, the beginning of one — as it was said that he (and many others) celebrated his sixtieth birthday (for so it was) with piles of caviar and bottles of vodka until five that morning, with Maestro returning to Mariinsky II only moderately late and charmingly disheveled to conduct the (scheduled) one-thirty curtain of Iolanta the next afternoon.

IV

The 4 May program of dance at Mariinsky II found Veniamin Vasilievich stage left in the Dress Circle with a fine view of both the dancers and the Tsar’s Box, wherein he could observe the great Maya Mikhaylovna Plisetskaya, who had been named prima ballerina assoluta at the Bolshoi some fifty years ago, and who presently perched with excellent posture and a look of vague interest at the goings-on beneath her.

Onstage, members of the Mariinsky Ballet performed Balanchine’s choreography for Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky’s Symphony in C. Veniamin Vasilievich found the dancers’ fluidity matched by Maestro Gianandrea Noseda’s gliding gait in the pit, but this was all a prelude to Bolero.

Maurice Béjart’s choreography of Maurice Ravel’s Bolero — a haunting diary of a madman, an obsessive ritual, a steadfast, unchanging, unrelenting melody of three hundred forty bars around which the orchestra grows and swells — assigns a female dancer (and in a later production, a male one) the role of melody, puts her on a pedestal, and assigns a wolf pack of men below her to the role of rhythm. The solo role was once danced by Maya Mikhaylovna Plisetskaya, whom it must be assumed taught it, in that great lineage of Russian instruction, to the presently pedestaled soloist below, Diana Vishneva.

Veniamin Vasilievich had seen Maya Mikhaylovna Plisetskaya’s Bolero on film (made in a time when such things were still filmed and elegantly produced) and so with this celluloid vision in his mind’s eye — a passionate, affirming and hypnotic performance by the former prima ballerina assoluta — he was unmoved by the rote rhythmic gymnastics that unfolded below like so many exercises from a fitness trainer. Diana Vishneva, it seemed to him, demonstrated technique without character, a series of movements that served no larger arc.

Even so, the combined chemistry of the men of the Béjart Ballet Lausanne and the Mariinsky Ballet generated enough energy and support to build electricity in the hall, so that when the finale came, sustained applause came with it. Diana Vishneva bowed and bowed and bowed again to the ecstatic crowd in the set-piece manner of ballerinas. She then directed her gaze (for once, noted Veniamin Vasilievich) skyward to the Tsar’s Box in order that she might acknowledge Maya Mikhaylovna Plisetskaya, who herself stood and bowed in the set-piece manner of ballerinas. Diana Vishneva returned the bow. Maya Mikhaylovna Plisetskaya returned her bow. Diana Vishneva returned the bow again. The crowd was thrilled and increased its fervor. Yet what had begun as deferential well-wishing was slowly taking on an air of brinkmanship. Maya Mikhaylovna Plisetskaya bowed yet again. Diana Vishneva followed suit. This continued another three minutes, now five. “I must get a picture!” bursted the woman sitting next to Veniamin Vasilievich, fumbling for her camera. The set pieces were becoming more elaborate. Onstage, they became feats of flexibility. In the Tsar’s Box, they were now direct appeals to the patrons with a sense of vogue la galère. Ten minutes of genuflection. Was fifteen possible?

“This is madness, surely,” thought Veniamin Vasilievich, who turned and found the door. He shut it behind him but could not shut out the frenzy of the crowd.

V

On 5 May, his final evening in St. Petersburg, Veniamin Vasilievich was himself seated in the depths of the Tsar’s Box, but at the elegant elder statesman Mariinsky I, for a tragically comic or comically tragic Nabucco — he could not be certain which, but found Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi underserved in either case. Was the cartoonish comedy intentional or a byproduct of the troglodyte sets and Cecil Blount DeMille costuming? The soprano Maria Agasovna Guleghina occasionally screeched her high notes as Abigaille. At one point, Veniamin Vasilievich noted that singers were spinning what appeared to be pipes. Hand-slapping occurred at random, choreography apropos of nothing. “Well, I’m off,” a bewildered American critic said to him as the celebrated Mariinsky curtain dropped for intermission. “Is there a bus?” he asked, and, not waiting for an answer, disappeared.

“The problem,” reasoned Veniamin Vasilievich to himself, “is that the company are tourists in Dmitry Alexandrovitch Bertman’s production, and perhaps in Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi’s opera, too. No one seems even moderately committed to the story! Even Plácido Domingo’s Nabucco, who has added one fine aria, feels uncertain — his enterprises, like Hamlet’s, losing the name of action.”

• • •

To accompany the smoked fish, many bottles of vodka (Russian Standard, of course) were drunk among the journalists at the table of Veniamin Vasilievich during the farewell dinner. Veniamin Vasilievich’s sense of geography, tenuous even in ideal conditions, had abandoned him entirely now. But his sense of time remained keen, and he remembered that 5 May was Russian Orthodox Easter Sunday.

So in honor of the holiday, after the bottles were emptied, Veniamin Vasilievich and others played tourist and made their way in a procession to one of St. Petersburg’s many historic churches. “It is cold — come inside, Veniamin Vasilievich!” beckoned the German.

Veniamin Vasilievich felt guilty walking into church on Easter Sunday tipsy, but the warmth of the incense calmed him. Believers bowed gently back and forth, hands across their chests, as they awaited communion from the deacons, who performed the mysteries of the church in sight of the parishioners with the familiarity of making pastry in a kitchen. A small choir wafted away any residue of Nabucco with the pure, clean lines — grounded by deep bass — of Russian polyphony.

Veniamin Vasilievich made his way upstairs to a beautiful room with vaulted ceilings of rich wood and gold leaf — and stood at the back. In front of him, the faithful bowed and ritually echoed a cantor’s chant. Veniamin Vasilievich sank into his overcoat as God’s love surrounded him.

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine -

A Simple Love Story

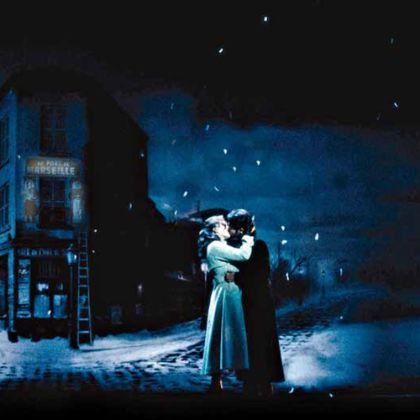

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine