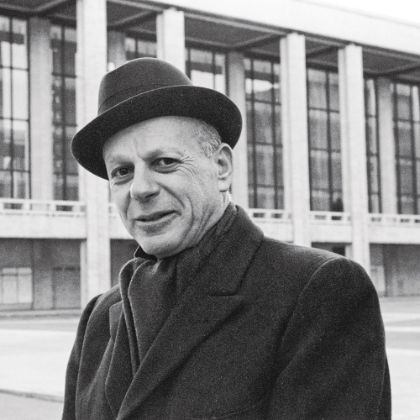

An appraisal of Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

By Jens F. Laurson

When Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau passed away this year, there were few superlatives raining down on him in obituaries that hadn’t already been used during his lifetime. He was one of three or four giants in classical music who were able to shape the cultural landscape — and he was the last one. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau need not have been your favorite singer in order to acknowledge his greatness and importance.

Like Herbert von Karajan and Leonard Bernstein, Fischer-Dieskau arrived right at the time when recording technology allowed for the easier-than-ever dissemination of music, when competition was limited, and when classical music still defined mainstream culture, even for those who didn’t much care for it. With some four hundred records to his name, Fischer-Dieskau became one of the most recorded singers of all time. In Germany he is called Der Jahrhundertsänger — literally that’s “singer of the century,” or “hundred-year singer,” although neither translation does justice to the air of veneration the term connotes. His complete recordings of Schubert, Schumann, Liszt, Wolf, Beethoven and Brahms and copious doses of other, less well-known Lieder composers were the record collector’s natural (and often sole) choice. There are few classical-music listeners above the age of thirty-five for whom Fischer-Dieskau’s interpretations of this repertoire didn’t leave the emotional footprint of first exposure.

The quantity and, at its best, quality, intelligence and matter-of-course-ness of his Lieder singing made German art songs known, even popular, in non-German-speaking countries. American critics, marveling at the quality of his Lied interpretations, were more reserved in their Fischer-Dieskaumania than their German and English colleagues, but not by much. Harold C. Schonberg called him “the most protean singer alive today,” saying he was “acknowledged to be the greatest of contemporary lieder singers [who] has triumphed in opera . . . from Handel to Henze [and] a stalwart in oratorio work.” Donal Henahan referred to Fischer-Dieskau as “that paragon of 20th-century singers.”

Fischer-Dieskau made his American debut with the Cincinnati Symphony on April 15, 1955 with Bach and Brahms. He was in New York almost annually until 1980 — for the first time on May 2, 1955, accompanied by Gerald Moore and tellingly performing Die Winterreise, still a rarity in recital then. Critics were bowled over by how he made German Lieder attractive. The words that repeatedly crop up in reviews of the time are “command,” “consummate taste,” “impeccable,” “text,” “intelligence,” “perfection” and, over and over, “control.”

Eventually a twinge of discontent entered. Donal Henahan was one of the first to note, for The New York Times in 1968, that “if Mr. Fischer-Dieskau has a fault, it may be his very mania for perfection, a bit too much polish in manner and interpretation obtrudes at times. One wants, especially in Lieder, more suggestion of spontaneity.” And writing for New York’s Aufbau after a Lied recital, Robert Breuer observed: “Carnegie Hall was like a temple: You could have heard a pin drop, that’s how reverently the community received the high priest of Lied.” In 1988, for Fischer-Dieskau’s last New York appearance, Henahan wrote: “Reverence hung in the air. . . . Silence reigned.” Fischer-Dieskau impressed two generations of listeners, singers and critics with his groundbreaking technique and the expressive shades he got from his voice. But he never made them cry.

A VOICE FROM RUINS

To Americans, Fischer-Dieskau was the messenger of Lied. To Germans, he was much more: a social phenomenon and a symbol of postwar Germany, “from the ruins risen newly/to the future turned, we stand,” to quote the East German national anthem. Fischer-Dieskau — young enough not to have been implicated in Fascism — was the Exceptional German whose pure tone rose from the cultural ruins the Nazis had left. With him rose faith in the good and noble within the German nation. He was the man who brought the German language back from a voice of barbarism. He became part of the national inventory, an indispensable accessory of the cultured German bourgeois, as ubiquitous as their lacquered root-wood furniture. Karajan’s Beethoven, Fischer-Dieskau’s Schubert and a Meissaen coffee set: these were the artifacts of choice to signal to the world, or at least the neighbors, that one was cultured. With these choices one could not go wrong; these choices didn’t compel questioning of the past.

If this was in part why Fischer-Dieskau was admired, it is also the reason why he causes many younger Germans, especially those influenced by the student movement of 1968, to cringe at his very name. When I suggested to a colleague we discuss “Fi-Di,” he shuddered. We talked and tried to trace that feeling, arriving ultimately at a greater discontent with the society of which Fischer-Dieskau was emblematic — an inherently unironic society, determined not to self-reflect; a society that engaged, still or again, in the mindless adoration of icons. In that climate, Fischer-Dieskau’s greatness became stifling, as did his perfectionism, his overly artful and precious treatment of the music, and the way he sang Bach: with pathos and an undercurrent of cultured piety.

Martin Anderson, founder of the Toccata Classics label, compared the effect of Fischer-Dieskau’s singing to that of Christian Gerhaher, both his and my favorite Lied baritone: “When Gerhaher sings, you feel you are spoken to. When Dieskau sings, it feels like you are being lectured.” And indeed, with Fischer-Dieskau you get emotions once-removed — studied, scrutinized and then delivered. His doubt and seething anger, for example, are scarcely believable; they’re just impressively depicted. The best among the contemporary crop of singers — Werner Güra, Christopher Maltmann, Florian Bösch and, most of all, Gerhaher — can get across emotions with such palpable realism that witnessing them becomes uncomfortable on the other, realistic side of the spectrum. In 1974, after a performance of Franck’s Les Béatitudes, the critic of the Bayernkurier wrote that Fischer-Dieskau was a singer “who takes great care not to give even an iota too much, and who denies himself absolutely to the rapture of the music.”

ERRING AND IRRELEVANCE

The level of discomfort Fischer-Dieskau causes in his detractors is understandable, but isn’t entirely or always rooted in the music. There are both good and misguided reasons to dislike aspects of Fischer-Dieskau. Similarly, there are both natural and imprudent reasons to admire him. “How do you criticize gods?” asks baritone Dietrich Henschel, half-jesting, of his former teacher. Presumably by trying to do them justice, in good and bad.

Blanket veneration for Fischer-Dieskau’s output is certainly ill-placed. The didactic approach to singing is no longer an artistically relevant expression. Ditto the awfully mannered, artificial super-neatness and the unbelievably upright, uptight bourgeoisness of his middle-to-late-period. There are better singers active today in all the repertoire Fischer-Dieskau shone in, albeit not one singer to cover them all. The cultural artifacts he left us are not and shouldn’t be sacrosanct, but because Fischer-Dieskau was such a dominant figure, Henschel adds, those artifacts still need the filter of time to be impartially assessed.

Many songs in his complete Schubert edition sound sight-read. In the less popular or less important songs (there are hundreds), the Hyperion Schubert set around pianist Graham Johnson is superior. For a devastating example of a Lied style best forgotten, listen to his Brahms German Folk Songs, where he partners with the queen of mannerism, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. Compare what they do to “Da unten im Tale” with Werner Güra’s rendition on his sublime Schöne Wiege meiner Leiden (Harmonia Mundi). A folk-like song of genuine simplicity and honest beauty turns false and creepy in the wrong hands.

Fischer-Dieskau’s Bach discography, too, demands picking out the raisins: At the very beginning of his recording career he was part of an eventually aborted cantata cycle for Berlin’s RIAS Chamber Orchestra with proto-Historically Informed Performance Bach-master Karl Ristenpart.1 Within the 1949–1952 set, meticulously restored and beautifully presented, you can hear Fischer-Dieskau in sixteen cantatas as an unmannered, clarion youth. His work for Karl Richter’s St. Matthew Passions — first as Judas in 1958 (Archiv) and 1959 (Profil Hänssler) and then as Jesus in 1979 (Archiv) — is part and parcel of a unique kind of Bach magnificence.

DIESKAU UNDENIABLE

Beethoven’s just-ever-so-slightly-awkward-yet-stupendous art songs suit Fischer-Dieskau well, perhaps because of their lack of chummy naturalness. Between the 1951 RIAS recording and the 1966 Deutsche Grammophon (DG) recording2 containing “Adelaïde,” that gem among Beethoven’s songs, Fischer-Dieskau’s Beethoven output is well covered.

Hugo Wolf fits Fischer-Dieskau’s bill, too, and the two discs he made with fellow twentieth-century classical music giant Sviatoslav Richter are exemplary. Together the two artists pry open the hidden treasures in Wolf with keen but subtle determination, intensity and — just — sufficient artlessness.3 4

THE WINTER TRAVELER

Schubert’s Die Winterreise was Fischer-Dieskau’s signature piece. He sang it over a hundred times in recital during his career. He presented it in his first public performance in 1942, as a boy of seventeen, with Berlin engulfed in war and air raid sirens interrupting the recital. In 1948 he started his recording career with a Winterreise for RIAS. He sang it for his New York City debut in 1955, about which John Briggs wrote in The New York Times, “Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, the German baritone, making his debut at Town Hall last night, performed the considerable feat of holding his audience’s interest and close attention throughout Schubert’s song-cycle, Die Winterreise. Not every singer, however gifted, is capable of this feat, especially in warm weather.” When he sang his last Winterreise in 1991 in Cologne (with Hartmut Höll on piano), Schubert’s “garland of garish songs” had become an inextricable part of his half-century-long career. If you include the restored 1948 recording with Klaus Billing (Audite)5, you can trace that career and his interpretation along his dozen recordings of that song cycle alone.

There is always someone to recommend any one of Fischer-Dieskau’s eight studio recordings of Winterreise and reject all others as wildly inferior, from his HMV/EMI effort with Gerald Moore in 1955 to his last take with Murray Perahia in 1992 (Sony). I got started on the 1966 DG recording with Jörg Demus,6 and perhaps that’s the reason I think it represents his most satisfying compromise of intrepidness, vocal freshness and relative unmanneredness, with a pianistic contribution that is equal parts supporting character and independent actor.

Fischer-Dieskau premiered at least sixty-six new works between 1952 and 1992.

OPERATIC DIESKAU

An easy criticism of Fischer-Dieskau is that he was no opera singer. His voice was not large enough, or not suited to the characters, too stilted or unnatural. Yet opera was an essential part of his career, from his first role on stage as Posa in Don Carlos under Ferenc Fricsay, to his Bayreuth debut at twenty-nine, to his one hundred twenty-three Salzburg Festival appearances, of which sixty-seven were in opera. Fischer-Dieskau as Don Giovanni should be awkward, but it kind of works — at least on the earlier Fricsay recording (DG), where you get a lot of the voice and little of the mannerism. With Die Zauberflöte, Fischer-Dieskau’s Papageno has been derided as a “Tourist in Lederhosen,” which is especially apposite for the Böhm recording, if much less so — again — in Fricsay’s (DG).

In Richard Strauss’s underrated last opera, Capriccio, Fischer-Dieskau suits the parlando of the music ideally.7 His darkly seething Rigoletto, under the baton of a fervent Rafael Kubelik8, finds him at his counterintuitive best, partly because he was incapable, for better or worse, of a buffoonish touch. His participation in Kempe’s Lohengrin9 as Telramund is a highlight of his opera career on record, as is his Wotan in Karajan’s gorgeously Italianate Rheingold10, where he strips years of stentorian Wotan interpretations off that role with his lyrical, mellifluous take.

CONTEMPORARY MUSIC CHAMPION

The area where Fischer-Dieskau most deserves, but is least given, undiminishable credit is in his tireless championing of contemporary music. As the story goes, he strong-armed Deutsche Grammophon into releasing Aribert Reimann’s stark, difficult, fascinating opera Lear11 in a luxurious LP edition, even though they thought it commercially unviable (as it probably was). Reimann — Fischer-Dieskau’s go-to accompanist in all unusual repertoire — wrote the part of the lonely, aging Lear to perfectly match the first hints of brittleness in Fischer-Dieskau’s voice. Their collaboration was a fruitful one, and Fischer-Dieskau premiered at least ten works by Reimann, more than any other composer. But premiering a work was no prerequisite for Fischer-Dieskau to believe in it; he took to Reimann’s Byron setting Stanzas to Augusta, an intensely emotional, overtone-rich quintet for baritone and string quartet, recorded it, and performed it until the last months of his career.12

On average, Fischer-Dieskau premiered more than one new work every year during his career, premiering at least sixty-six between 1952 and 1992. He was a formidable champion of Hans Werner Henze (Neapolitan Songs, Elegy for Young Lovers)13, Henze’s teacher Wolfgang Fortner, Gottfried von Einem, Ernst Krenek (including his wacky The Dissembler), Luigi Dallapiccola (Preghiere), Michael Tippett (The Visions of Saint Augustine), Samuel Barber (Three Songs), Witold Lutosławski (Les Espaces du Sommeil), several composers already lost to time, and, of course, Benjamin Britten. Fischer-Dieskau sang in the premieres of Britten’s War Requiem14, Cantata misericordium and the Songs and Proverbs15 that set texts by William Blake. Fischer-Dieskau performed Zimmermann and Blacher; recitals with Berg, Schönberg and Webern; Stravinsky, when it was contemporary music; and always and again Busoni’s Doktor Faust. The latter was one of his signature roles, recording it (with slight cuts) with Ferdinand Leitner for DG. Kent Nagano’s complete (and equally out of print) 1998 recording with Dietrich Henschel as Faust pays tribute to Fischer-Dieskau by including him as the speaker. (The extant Adrian Boult recording with Fischer-Dieskau is a mere medley of scenes.)

“Fischer-Dieskau used the name and media control he’d made for himself in conservative music and brought it to bear on contemporary works,” Henschel says, “even though he didn’t bring the scrutinized perfection of his Mahler16 or some Schubert17 to these works. Whether in Wozzeck or something by Reimann, Fischer-Dieskau approached the music with a ‘good-enough’ attitude, with notes and pitches often approximated. But composers knew that, and Fischer-Dieskau still helped the music with his performances and recordings more than anyone else could have.”

POSTLUDE

Henschel is keen to convey that in private, Fischer-Dieskau the teacher had nothing of that professorial attitude about him that he allowed his public perception to become: “He wasn’t at all like the daunting recitalist. Instead he listened and then simply tried to nudge one’s own interpretation in ways that allowed the pupil to do the same thing more elegantly or better. All those true clichés were negated in those fifteen private lessons.”

I admire Fischer-Dieskau most for his dedication to the wonderful and woefully underrated Othmar Schoeck (1886–1957), James Joyce’s favorite composer, whose idiom after 1945 was too unacceptably romantic for avant-gardists but too modern for conservatives. Fischer-Dieskau was the first to record Schoeck’s boundary-pushing masterpiece and epitome of extreme, late romantic music, Notturno for baritone and string quartet. And he recorded other risky, delicately gorgeous Schoeck works: Das Holde Bescheiden, Unter Sternen18, Das stille Leuchten19 and Lebendig begraben. Maybe Fischer-Dieskau’s death will kindle a series of reissues of these artistically significant recordings. If death be brisk business, let’s have it serve a musically worthy cause, not just revisit repertoire much traversed.

…

Das Lied

Art songs are characterized by having a known author, spelled-out accompaniment and a more complex form. They are usually set to independent poetry and are more challenging to perform. Lied (plural Lieder) simply means “song” in German, but the loanword in other languages specifies German Art Songs in the romantic tradition, epitomized by the finely crafted ballads and elaborate song cycles of Carl Loewe, Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann and carried on by the likes of Johannes Brahms and Hugo Wolf.

The boundaries between art and folk song can be porous: Brahms set extant folk songs for his Volkslieder and brought them into the art-song fold; Schubert’s “Lindenbaum” from the song-cycle Die Winterreise morphed into a folk song after a simplified choral arrangement of it became popular. The easiest way to tell the difference: if it’s in German and the singer raises his or her eyebrows before starting, then it’s a Lied.

…

1.

Johann Sebastian Bach

Cantata Recordings for RIAS

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, et al

RIAS Chamber Orchestra

Karl Ristenpart, conductor

(Audite)

2.

Ludwig van Beethoven

“An die ferne Geliebte,

Adelaïde” and other songs

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Jörg Demus, piano

(Deutsche Grammophon)

3.

Hugo Wolf

Mörike-Lieder

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Sviatoslav Richter, piano

(Deutsche Grammophon)

4.

Hugo Wolf

Goethe-Lieder

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Sviatoslav Richter, piano

(Orfeo D’or)

5.

Franz Schubert

Die Winterreise

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Klaus Billing, piano

(Audite)

6.

Franz Schubert

Die Winterreise

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Jörg Demus, piano

(Deutsche Grammophon)

7.

Richard Strauss

Capriccio

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (as Olivier),

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, et al

Philharmonia Orchestra

Wolfgang Sawallisch, conductor

(EMI)

8.

Giuseppe Verdi

Rigoletto

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (as Rigoletto),

Renata Scotto, et al

Orchestra and Chorus della Scala

Rafael Kubelik, conductor

(Deutsche Grammophon)

9.

Richard Wagner

Lohengrin

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (as Telramund),

Gottlob Frick, Jess Thomas, Elisabeth Grümmer

Vienna Philharmonic

Vienna State Opera Chorus

Rudolf Kempe, conductor

(EMI)

10.

Richard Wagner

Das Rheingold

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (as Wotan),

Gerhard Stolze, Erwin Wohlfahrt,

Martti Talvela, et al

Berlin Philharmonic

Herbert von Karajan, conductor

(Deutsche Grammophon)

11.

Aribert Reimann Lear

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, et al

Bavarian State Opera Orchestra

Gerd Albrecht, conductor

(DG Archiv)

12.

Aribert Reimann

Unrevealed, Shine and Dark

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Cherubini String Quartet;

Aribert Reimann, piano

(Orfeo)

13.

Hans Werner Henze

Elegy for Young Lovers

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (as Gregor Mittenhofer),

Martha Mödl, et al

Radio Symphony Orchestra Berlin

Hans Werner Henze, conductor

(DG Archiv)

14.

Benjamin Britten

War Requiem

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Peter Pears,

Galina Vishnevskaya, et al

London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus

Benjamin Britten, conductor

(Decca)

15.

Benjamin Britten

Songs and Proverbs (with Billy Budd)

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Benjamin Britten, piano

(Decca)

16.

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 1; Songs of a Wayfarer

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra

Rafael Kubelik, conductor

(DG)

17.

Franz Schubert

Schwanengesang;

Erlkönig; Ständchen;

Nacht und Traume; et cetera

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Gerald Moore, piano

(Decca)

18.

Othmar Schoeck

Unter Sternen

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Hartmut Höll, piano

(Claves)

19.

Othmar Schoeck

Das stille Leuchten

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Hartmut Höll, piano

(Claves)

related...

-

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Back to Bach

Pianist András Schiff revisits The Well-Tempered Clavier and other totems of J.S. Bach — on stage and on record.

Read More

By Bradley Bambarger -

From Christemasse to Carole

The birth of Christmas in medieval England

Read More

By David Vernier