on art and power

British author Julian Barnes writes a Russian novel.

By Robert Hillinck

The Soviet system was constructed at an energetic moment in Europe’s history. Reeling from the shock of the First World War and unburdened from the weight of nineteenth-century cultural mores, several modernist movements entered their most avant-garde phase in the 1920s. At the same time, governments across the continent and the world were becoming just as bold, exploring and implementing the concept of social engineering. They dreamed that society’s ailments, having been meticulously studied by eminent social scientists, could be cured with “enlightened” policies that used the total power of government to remold society and economy — and the people that comprised them.

Responsibility for the latter transformation fell to artists, in the case of the Soviet Union. Famously proclaimed by Stalin as the “engineers of human souls,” poets, theater directors, sculptors, musicians and other cultural workers enjoyed — or, rather, endured — more government oversight and suspicion than the normal population. Standards were put in place after Stalin’s rise to power that regulated what was stylistically and thematically acceptable in art of all genres, and unions were established to enforce them. Noncompliant artists were, at best, kicked out of the unions and forced into inactivity. At worst — and far more frequently — they were disappeared, either sent to prison camps in the East or summarily executed as part of a bitter campaign of internecine purges.

It’s impossible to know how genuinely Stalin and his cultural commissars believed their own language about the importance of artists, but historians can assess the effects of their policies and cultural standards. Ultimately, these stylistic regulations had little to do with inspiring proletariat-friendly art and much more with controlling the artists making it. One of the most famous artists hounded by the Soviet state was Dmitri Shostakovich, whose career-long struggles with the state have become the stuff of legend. His story continues to fascinate historians, artists and audiences alike, and has inspired some of the most heated battles in musicians’ political memory since Beethoven and Wagner.

The newest installment of this niche cultural battle is The Noise of Time, the most recent book from Julian Barnes, a British novelist who netted the Man Booker Prize for his 2011 novel The Sense of an Ending. Barnes readers and fans of this last success are sure to recognize the stuff that makes up The Noise of Time, namely a series of introspective vignettes that rotate and coalesce around pivotal moments in the protagonist’s life to give a fully fleshed-out rendering of its subject and world. For Shostakovich (via Barnes), these come to us as “conversations with Power,” or three moments when his career, life and art were on the line — moments when the State targeted him in an effort to gain closer control over one of their most valuable “engineers.”

The first conversation falls after the Party apparatus collapsed on Shostakovich for his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, which was infamously pilloried in a Pravda op-ed after months of commercial and critical success. Shostakovich was forced to renounce the opera and retracted his fourth symphony, yet he was still targeted for interrogation by the secret police at the height of the purges. A decade later, he had his second “conversation with Power,” this time with Joseph Stalin. During the War, Shostakovich had cemented his value through the composition of patriotic works like his “Leningrad” Symphony No. 7, and his worldwide fame led Stalin to ask him to represent the Soviet Union in New York City at the Cultural and Scientific Congress for World Peace, where he was obligated to denounce his idol Stravinsky. The third conversation occurred well after his tormentor, Stalin, had died. In the 1970s — after Krushchev’s ostensible “thaw” and the retreat from Stalinism — he was hounded by the Party rep Pyotr Pospelov and eventually caved, joining the Party that had tortured him for the duration of his career. Readers see how Shostakovich’s perspective shifts with each encounter, and assess the bitter price of survival for an artist trapped in a twisted system where life was bought with concession.

Each of these “conversations with Power” affords Barnes the opportunity to explore the fraught relationship between Art and Politics. What does the artist owe his government? What does he owe himself? Can music mean something, or make political commentary? If so, can a composer be ironic or sarcastic with his art? If not, can he even speak of irony? Barnes wrestles with all of these questions admirably, without allowing the drama of Shostakovich’s life or the story of the Soviet Union to get bogged down in these interior meditations. Some of the questions are even posed outright, one of the most important rearing its head in Shostakovich’s tongue-in-cheek exam question to a distressed conservatory student: to whom does art belong?

In the tradition of all great Russian literature, Barnes also uses the abstract conflict of Art and Politics as a condemning example of the Soviet Union’s wider pattern of real abuse, absurdity and hypocrisy. One classic target is the arbitrary nature of total power and its decisions, so perfectly demonstrated by the Lady Macbeth episode.

The same principles are equally encapsulated by the cultural fallout from the Nazi–Soviet Pact in 1939: overnight, Sergei Eisenstein was forced to suppress his anti–German film Alexander Nevsky and start work on a Bolshoi production of Wagner’s formerly unperformable Walküre. Of course, when the Germans broke faith in 1941 and poured into the Soviet Union, Nevsky was immediately revived, and Wagner became a vile fascist again.

Barnes’s research shines through The Noise of Time, but this great strength leads to the book’s largest fault. It seems confused at times: is the book a history, a biography or a novel? This is not to say that the history was misplaced or incorrect. Indeed, all Russian novels rely on their history, so it only makes sense that novels about Russia should also provide their readers with the requisite context. The components are all there in The Noise of Time, and they are often stitched together with great art and finesse. At other times, however, the momentum of Shostakovich’s vibrant internal monologues and remembrances is drawn up short as Barnes feels obligated (rightly) to lay out the historical background. The stitches become visible. Regardless, The Noise of Time stands as a moving and human portrait of a fascinating figure of the twentieth century.

related...

-

Seeking Carlos

Maestro Carlos Kleiber holds the record for the greatest Beethoven Fifth.

Read More

By Daniel Felsenfeld -

Sound and Vision

A top twenty-five of Bowie beyond the hits

By Bradley Bambarger

Read More -

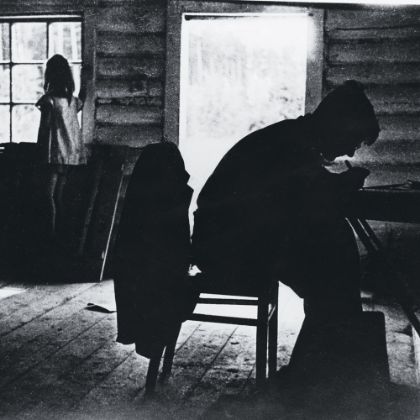

Raw Emotion, Coagulated Blood, Vodka and Gunpowder

The Substance of Shostakovich’s Fourth

Read More

By Jens F. Laurson