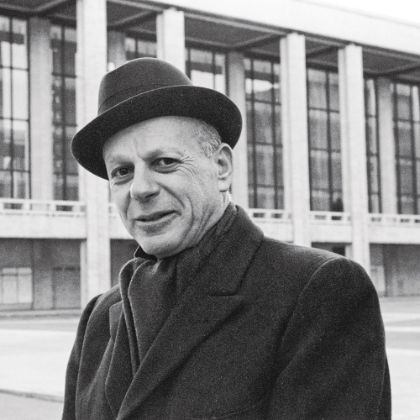

A Matinée Idol

How Leopold Stokowski converted America to orchestral music

By Colin Eatock

A century ago, America’s wealth and burgeoning musical opportunities made the nation a magnet for European conductors. Some of these men — such as Gustav Mahler, Arturo Toscanini and Serge Koussevitzky — had already achieved fame in their homelands, and were greeted in the United States as musical celebrities.

No hero’s welcome attended the arrival of Leopold Stokowski. When he first came to New York in the summer of 1905, the tall, handsome English–born musician was almost unknown in America. But at just twenty-three years of age, he was eager to make his mark.

Stokowski’s reputation as one of London’s leading church musicians had helped him secure a prominent position in New York — as organist at St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church. He wasn’t a conductor yet, but that would soon change, and with it, music in America.

Always looking to his own advantage, Stokowski made valuable connections in New York. He descended from his organ loft to charm high-society ladies. Soon he was romantically involved with the young concert pianist Olga Samaroff, née Lucie Hickenlooper. His job also allowed him to spend his summers in Europe, where he learned conducting by keenly observing maestros at work.

Stokowski was in Paris in 1908 when Samaroff wrote to him with the news that the position of conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra was open and urged him to apply. Stokowski — ever the opportunist — rose to the challenge.

Stokowski’s conducting experience had heretofore been limited to church oratorios. But when the conductor of a Paris orchestra fell ill, Samaroff pulled strings to have her beau step in. About a week later, a violinist friend asked Stokowski to conduct a concert in London. This insubstantial experience as an orchestral conductor was nevertheless enough to satisfy the board of directors in Cincinnati that he was the real thing, and they offered him a contract.

Stokowski’s career in Cincinnati had the brightness and brevity of a comet. He toured Ohio with his orchestra, winning high praise for his players and himself. “He has the spark of creative genius that knows no age,” declared one Cleveland newspaper. Yet he lasted for only three years in Cincinnati (until 1912), when his relationship with the board of directors deteriorated. This sort of thing would be an ongoing problem in his career. He sought early release from his contract, which was granted — after he made the conflict public.

His resignation became a scandal when it was revealed that Stokowski had signed on with The Philadelphia Orchestra as music director, starting in the fall of 1912. Had he deliberately flouted his contract with Cincinnati for a better job in Philadelphia? Stokowski denied it all, of course — but was pleased to leave the Midwest for somewhere more sophisticated. “This is a great city,” he told Samaroff (now his wife), when he arrived in the City of Brotherly Love. “It must have a great orchestra.”

That was exactly what he gave Philadelphia. His tenure with the city’s orchestra, from 1912 to 1941, is one of the great eras of American musical history. “Stoki” (as he was fondly known) and Philadelphia soon turned out to be a match made in heaven. Adored by his public and backed by the city’s wealthy elite, the glamorous maestro was free to indulge his ambitions — and he had no lack of them.

He tinkered with different seating arrangements for his orchestra. He introduced free bowing in the strings (rather than unison up-and-down movements) to create the distinctive “Philadelphia sound.” His grand orchestral arrangements of organ works by J.S. Bach appeared on programs, giving rise to a new verb: to “Stokowski-ize.” And he introduced new music to America — leading the U.S. premieres of Mahler’s Symphony No. 8, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and Berg’s Wozzeck, among many others.

Stokowski’s showman’s instincts led him to look beyond the walls of Philadelphia’s Academy of Music for new ways to disseminate his art. He recorded extensively, pioneering electrical recording with microphones in 1925. His radio broadcasts were heard across the country, and he organized the first transcontinental tour of a major orchestra, taking his musicians to Los Angeles and back in 1936 — with a gruelling itinerary of thirty-three concerts in twenty-seven cities over thirty-five days.

He loved the camera, and the camera loved him. He appeared as a conducting actor in the Hollywood films The Big Broadcast of 1937 and One Hundred Men and a Girl. And in 1936, a chance meeting with Walt Disney led to the creation of Fantasia, released four years later. For the animated film, Stokowski conducted an eclectic mix of pieces — ranging from his own arrangement of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring — and famously shook Mickey Mouse’s hand.

But by this point his association with the Philadelphia Orchestra was on a steep decline. Dissatisfied with the board of directors, Stokowski had formally resigned as music director in 1936, but continued to lead the orchestra until 1941 (sharing duties with Eugene Ormandy). The years had also taken a toll on his personal life: he and Samaroff divorced in 1923, and his second marriage to Evangeline Brewster Johnson (of the Johnson & Johnson pharmaceuticals family) ended in 1938, after Stokowski had a fling with the actress Greta Garbo.

However, Stokowski wasn’t about to let the grass grow under his feet. In 1940 he established the All–American Youth Orchestra. Following auditions across the country and a few weeks of intense rehearsals, Stokowski took his new ensemble on a twenty-one-concert tour of South America. In the next year, Stokowski toured North America with his young musicians. The All–American Youth Orchestra disbanded in 1941, after making several recordings for Columbia Records.

Other opportunities soon presented themselves. In 1941, the conductor Arturo Toscanini took a sudden leave of absence from the NBC Symphony Orchestra. Stokowski was offered the position on an interim basis and led the orchestra for two years. And with America’s entry into World War II, he conducted benefit concerts for the USO and the Red Cross, and even led some army bands.

In 1944, at the request of New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia, he accepted the baton of the newly founded New York City Symphony Orchestra. (His tenure with the orchestra only lasted for a year; again, he quarrelled with the board of directors.) In 1945, he founded the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra in Los Angeles — and discreetly slipped across the border to marry his third wife, the heiress Gloria Vanderbilt, in Mexico.

With the end of the war, Stokowski was again interested in a long-term appointment with a major U.S. orchestra. He guest-conducted the New York Philarmonic for several years, recording extensively, hoping to win the position of music director. But he was just one of several guest conductors vying for the job — others were Charles Munch, George Szell, Bruno Walter and Dimitri Mitropoulos, and in 1950 Mitropoulos was awarded the position.

Four more years of guest-conducting in the U.S. and Europe followed. His career seemed to lack direction — until, in 1955, the Houston Symphony Orchestra made inquiries about his availability to be music director. Stokowski readily accepted. He held this position in Houston for six years, raising the orchestra to new heights. But in 1961 (true to form), his relationship with the orchestra’s board of directors soured.

The breach with Houston came over a racial incident. Stokowski engaged three Houston-area choirs to perform Arnold Schoenberg’s massive Gurrelieder — including an African American chorus from Texas Southern University. The white choirs refused to share the stage with black singers, and the orchestra’s directors backed their position. Stokowski said he could not work in “an environment so full of prejudice” and left town.

By now, Stokowski was almost eighty —and a lesser man might have simply retired. Instead, he threw himself into yet another challenge: establishing a new orchestra in New York City. The Philharmonic’s move to the newly built Lincoln Center meant that there was no longer a resident orchestra at Carnegie Hall. Stepping boldly into this vacuum, he created the American Symphony Orchestra.

Delighted to finally have a first-rate New York–based orchestra to call his own, Stokowski devoted almost all his energies to the ASO. He took no fees for his services, and even paid the ensemble’s debts from his own pocket. He insisted that ticket prices should be kept low, and encouraged young people to attend concerts. And he didn’t shy away from difficult repertoire: in 1965, he led the world premiere of Charles Ives’s complex Symphony No. 4.

At long last, Stokowski had “arrived” as America’s senior man on the podium. He graciously accepted offers to guest-conduct the Philadelphia Orchestra, and led the Boston Symphony on a ten-concert tour. His ninetieth year — also the tenth anniversary of the American Symphony Orchestra — was marked by special celebrations in New York. He was made an honorary member of the Academy of Arts and Letters, and RCA and Decca issued commemorative LPs. Then, at the peak of his fame, he announced he was going home.

His return to England in 1972 had nothing to do with retirement plans. He conducted the major London orchestras, and recorded carefully chosen works, well aware that his final recordings would be his legacy to the world. At the age of ninety-four he signed a six-year contract with Columbia Records — fully intending to conduct to his hundredth year! But it was not to be: Stokowski passed away in 1977 at the age of ninety-five.

Stokowski was always controversial. He could be stubborn and unyielding. He was a “self-invented” man, speaking in a strange accent that was neither English nor Polish nor anything else. His flamboyant style made him an easy target for people who preferred a more serious or ascetic kind of conductor. He offended purists by liberally rearranging the music he performed, and his interpretations were sometimes criticized for offering more sizzle than steak.

Yet throughout his long career, he was enormously effective as a popularizer of orchestral music. And if his approach wasn’t especially “structural,” no conductor has ever achieved more through sonority and color. Stokowski left behind hundreds of recordings, and a major ensemble — the American Symphony Orchestra — that still plays at Carnegie Hall. He admitted women into his orchestras — not just as a token gesture, but in substantial numbers. And although his All–American Youth Orchestra was short-lived, Stokowski lent his stature to an ideal that has since spawned a thousand youth orchestras.

Leon Botstein, current music director of the American Symphony Orchestra, was a teenager when he first heard the ASO play under Stokowski. And today he sees Stokowski’s colorful style as the harbinger for a new kind of orchestral conductor in the twentieth century.

“Stoki cut a dashing figure,” recalls Botstein. “He was a matinée idol, and became a personality — and that was resented by conductors who weren’t like that. And he never gave a boring performance. People would accuse him of vulgarity, a but that’s a code-word for his gift for the dramatic qualities of music.”

America’s orchestras today wouldn’t be what they are, or where they are, without his influence.

The Stokowski Sound

Bach by Stokowski

Bach by Stokowski

Leopold Stokowski Symphony Orchestra

Leopold Stokowski, conductor

(EMI)

Leopold Stokowski’s transcriptions of works by J.S. Bach have been dismissed by purists as very, very unpure. And, to be sure, his reworking of Bach’s music into rich blasts of orchestral color expands Bach’s ideas beyond anything the old Kappellmeister could have imagined. Yet the naysayers miss the point: Stokowski’s arrangements of Bach (or any other composer) are new works of art — vivid and authentic manifestations of their own values. And who can say Bach wouldn’t have liked them?

Bach by Stokowski is a compilation of arrangements, recorded in 1957 and 1958, by a studio ensemble called the “Leopold Stokowski Symphony Orchestra.” It’s full of Bach favorites: the “Air On a G String”, the D Minor Toccata and Fugue, the “Little” G Minor Fugue, and much more — in digitally remastered glory live. —Colin Eatock

Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 9

London Symphony Orchestra

Leopold Stokowski, conductor,

(Decca)

Stokowski first recorded Beethoven’s Ninth with the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1934, well before the days of stereo, or even magnetic tape. Fortunately, Stokowski re-recorded Beethoven’s last and grandest symphony in 1967 with the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus — using technology vastly superior to what was available just three decades earlier.

In Stokowski’s hands, the LSO’s Ninth opens with a blast of drama, energetic and rich in dynamic contrast. The Second Movement is precise and methodical (not as fast as some conductors take it) and the Third Movement is lush and lyrical. The Finale is broad and expansive, but not overburdened with solemnity. They’re singing about joy, after all. —Colin Eatock

The Columbia Stereo Recordings

The Columbia Stereo Recordings

Philadelphia Orchestra

American Symphony Orchestra

National Philharmonic Orchestra

Leopold Stokowski, conductor

(Sony Classical)) (10 CDs)

These recordings include the last that Stokowski made and include his devotion to contemporary music (Ives‘ Fourth Symphony, Robert Browning Overture, and some choruses), his beloved Bach (three chorale prelude transcriptions plus Brandenburg Concerto No. 5), Romantic favorites (Mendelssohn‘s Italian Symphony, Brahms‘ Second and Tragic Overture, Silbelius‘ First and The Swan of Tuonela, Bizet‘s Symphony in C), orchestral blockbusters (his sensational Bizet Carmen and L‘Arlésienne Suites, Tchaikovksy‘s Aurora‘s Wedding, Falla‘s El amor brujo, and Stokowski‘s own “synthesis” of love music from Wagner‘s Tristan und Isolde — twenty-six minutes of it, no less, played with orgasmic richness by the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Every disc in this set offers a testament to a conductor of inimitable style and personality. With Stokowski, there‘s never any doubt about who‘s truly in charge. Mahler used to say that there are no poor orchestras, only poor conductors. This set proves him right. —David Hurwitz

related...

-

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Back to Bach

Pianist András Schiff revisits The Well-Tempered Clavier and other totems of J.S. Bach — on stage and on record.

Read More

By Bradley Bambarger -

Evolution of Form

Everything you always wanted to know about Baroque concertos (but were afraid to ask)

Read More

By David Hurwitz