Britten’s masterful treatment of A Midsummer Night’s Dream has a magic all its own.

By Thomas May

More than any other play by Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream cries out for musical response. Composers across the centuries have found themselves spellbound by its nocturnal world of hallucination, out-of-sync desire, and puckish mischief. Mendelssohn’s famously precocious Overture helped point the way toward a new concept of program music, while the late German composer Heinz Werner Henze [see page 96] found inspiration for his Eighth Symphony after rereading Shakespeare’s comedy from the 1590s. In just the past decade, the play prompted Elvis Costello to “go classical” and try his hand at writing an entire ballet score (Il Sogno).

But what to make of the Bard’s forest of enchantingly confused sounds, the source of “so musical a discord, such sweet thunder?” How can a composer go beyond playing mere accompanist and simply accessorizing Shakespeare’s own word-music with new-fangled sonorities? Most challenging of all: is it really possible to take on the play as a whole — its distinct levels of meddling fairies, misguided lovers, and hilariously inept band of wannabe actors — and craft a coherent opera that doesn’t cheapen Shakespeare’s tang of ambiguity?

Benjamin Britten found a way to translate Shakespeare into operatic terms more persuasively than any attempt since Verdi. In English opera, the only contemporary work that comes close is Thomas Adès’ The Tempest. Britten’s treatment of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in particular underscores his ability to bridge distances of medium and history in the service of a profoundly humanistic outlook. In a century that saw classical music increasingly marginalized from the larger culture and relegated to the province of “specialists,” Britten held fast to his vision of how it could play a central role in modern life. “The composer’s duty, as a member of society,” he once declared, “[is] to speak to or for his fellow human beings” — a belief reminiscent of the seriousness of purpose guiding his illustrious predecessors.

By a happy coincidence, this major anniversary year for two of opera’s top guns, Verdi and Wagner [see page 40], overlaps with Britten’s centenary. All three composers possessed a unique genius for combining music with theater, making opera the ideal vehicle for connecting them with an audience. The premiere of Britten’s Peter Grimes in 1945 — the first opera to be staged in London since the Blitz — was widely hailed as the inauguration of the genre’s renaissance. Britten seemed to embody the potent expectations newly unleashed by the end of the war; after Grimes made its Metropolitan Opera debut in 1948, Time Magazine put the composer on its cover.

Contemporary British composer Robin Holloway, in an assessment shortly after Britten’s death in 1976, praised Britten’s music for showing “how old usages can be refreshed and remade, and how the new can be saved from . . . lack of connection and communication.”

For Britten, the imperative to communicate hardly meant regurgitating the same successful formula. Britten followed Grimes with a radical change of tack, turning away for several years from the resources of grand opera to experiment with a series of chamber operas intended both “to tear all the waste away” and to be easier to produce. For his later operas, he took inspiration from Japanese Noh theater (Curlew River, the first of his “church parables,” from 1964) and wrote an opera for television (Owen Wingrave, his second work based on the fiction of Henry James, from 1971).

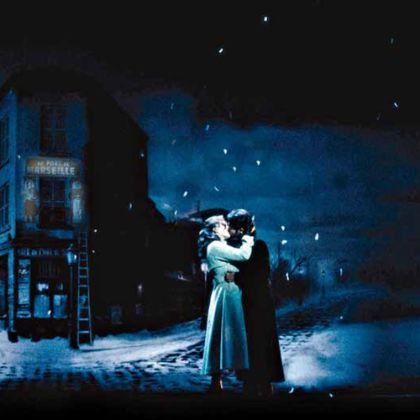

Grimes and, to a lesser extent, Billy Budd (1951), both with large casts, remain the best known of Britten’s operas. But A Midsummer Night’s Dream stands as the most enchanting, and arguably most immediately appealing, example of his ability to reinvigorate opera with a sense of freshness during a period when widespread audience distrust in new music was the norm. A testament to Britten’s mature mastery of the form, Dream represents a kind of missing link between Verdi’s Shakespearean triumphs in the nineteenth century and our own era.

Dream came about because a major new work was needed for the Aldeburgh Festival, which Britten had founded with colleagues in 1948 as an annual summer arts event where his latest operas could be presented. Situated in a moody, windswept coastal town in the composer’s native Suffolk, the festival had hitherto made do with a modest civic hall as its main performance space. But funds had been raised to rebuild this into, in Britten’s words, “a proper little opera house” in time for the 1960 festival. Britten therefore composed Dream at lightning speed, to inaugurate the refurbished venue with a big new opera that would be suitably “festive.”

The choice of Shakespeare, he explained, “has the essential advantage of having a libretto ready.” Britten’s working method typically involved time-consuming, argument-ridden sessions with his librettists, but for Dream this step could be bypassed: The text was already there. Collaborating with tenor Peter Pears, his life partner and a cofounder of the festival, Britten decided to set Shakespeare’s actual words rather than paraphrase them.

Pears and Britten crafted a workable three-act libretto by cutting roughly half of Shakespeare’s lines. They axed the expository opening set in Athens, changed the order of several scenes and redistributed several lines to a chorus of fairies. Still, amazingly, their adaptation required only one non-Shakespearean line to be interpolated.

These cuts don’t merely streamline Shakespeare’s plot. They reshape the essence of the story, centering it around the magical realm of the fairies who hold sway in the wood. The comically shifting variables in the equation of desire eventually solved by the end of the night are all set in motion by the fairy king Oberon. Everything is triggered by his initial conflict with his wife Tytania, who refuses to hand over for his private use the changeling boy she protects.

Each of the two classes of humans who happen to be passing by in the wood — the fleeing Athenian lovers and the rustics rehearsing their play for the court — falls prey to the intervention of Oberon and his henchman, Puck. The brief dalliance between Tytania and Bottom engineered by the fairy king occupies the symmetrical center of Britten’s opera, while the two Athenian couples inspire one of the score’s most ravishing ensembles when their desires are at last correctly aligned.

Britten draws on his stock of experience as a musical dramatist to map out the play’s various realms as distinctively as Shakespeare does through language and tone. Instead of a smoothly homogeneous wash of orchestral sound throughout, Britten isolates particular orchestral timbres and contrasting articulations to introduce the magical wood and fairy world (woozily gliding string chords that resemble the sighing of moonstruck dreamers, along with an ethereal mix of celesta, percussion and harps), the mismatched lovers (a more “conventionally” Romantic blend of strings and winds) and the rustic players (mostly in the lower register, especially bassoon and gruff trombone).

The vocal characterizations, meanwhile, cover a broad swath of operatic history. Tytania is a coloratura queen of the fairies; the lovers a standard four-part quartet; the rustics a buffa-like ensemble, with weight given to the low voices. Appearing in the final scene — the only one set outside the wood, at the court in Athens — Theseus and Hippolyta are cast as a regal bass and contralto.

Once again, Britten saves his most surprising touches for the fairy realm. He conceived Oberon for Alfred Deller, the pioneering countertenor. Overturning conventional associations of authority with a virile, powerful low voice, Oberon’s countertenor sonority intensifies his uncanny presence. The high-pitched fairy world is further complemented by a chorus of children’s voices. Puck is cast as a speaking role (accompanied by trumpet and drums), to be played by a “boy acrobat.”

In addition, Britten’s use of the countertenor voice instills an archaic flavor into the score. At the time of A Midsummer Night Dream’s composition, the rediscovery of a whole universe of early music was beginning to accelerate. And Britten had a particular fascination for the legacy of seventeenth-century composer Henry Purcell, a model for some of the most arrestingly beautiful passages given to Oberon. (Purcell’s own The Fairy-Queen, a suite of instrumental music, represents an early musical response to Shakespeare’s play.) Another slice of music history finds its way into the hilarious final scene, when the rustics perform what they call the “lamentable comedy” of Pyramus and Thisbe. Here Britten constructs an entire miniature opera crammed with insider jokes spoofing bel canto clichés.

At the same time, Britten incorporates his then-recent interest in atonality. But he does so from the perspective of a tonalist, organizing twelve-tone patterns as yet another easily recognizable coloristic device for his palette. For example, a mesmerizing sequence of four chords that also spells out all the notes of a twelve-tone row serves as the motif for the magic sleep at the opera’s center. The setting of familiar chords in unfamiliar contexts becomes a memorable sonic metaphor for the in-between states that occur in the enchanted wood and for the juxtaposition of dreams and reality.

If all this sounds too neatly schematic, Britten weaves these elements together into a coherent, richly satisfying emotional experience that doesn’t merely accompany Shakespeare’s play. The operatic Dream is an entirely independent work, exploring priorities of its own through Britten’s vivid musical treatment. Here, in place of the corruption of innocence that the composer chillingly depicted in his preceding opera, The Turn of the Screw — a theme that would preoccupy the composer for much of his career — erotic mischief paves the way to a hauntingly ambiguous reconciliation that lingers in the ear long after we awaken from our slumber.

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine -

A Simple Love Story

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine