Embracing The Planets

Holst’s suite of tone poems is much more than a pristine entrée into classical music.

By Ben Finane

Gustav Holst retains a seat in the pantheon of twentieth-century composers thanks entirely to the lasting popularity of his masterwork, The Planets. Written from 1914 to 1916, each of the suite’s seven tone poems takes the name of one of the spheres, with the exception of Pluto (then undiscovered, now disavowed) and our own. Though he draws on Mahler’s lyricism (“Saturn”), Stravinsky’s rhythm (“Mars”) and Debussy’s impressionism (“Mercury”), Holst’s voice is unique. His passion for the folk music of his country and his interest in astrology combined to capture, in the words of fellow Englishman Ralph Vaughn Williams, the “perfect equilibrium of two sides of Holst’s nature, the melodic and the mystic.” From the audiophile’s perspective, The Planets’ insatiably large and varied orchestration offers exciting acoustical possibilities. And despite the work’s use of complex rhythms and bitonality, The Planets remains one of the most accessible entrées into classical music, as evidenced by the long line of imitations churned out by film composers.

The work opens with “Mars, the Bringer of War,” a violent enactment of an ultimately self-destructive war machine, bristling with blaring brass and a strident ostinato in the percussion. Presaging World War I (the movement was completed in 1914 before the outbreak of war), “Mars” speaks to the cold inhumanity and futility of war — or, to reference only one of the many ads that have co-opted the music, the unstoppable power of the Pontiac GTO. “Mars” is followed by “Venus, the Bringer of Peace,” a calm, soothing contrast to the earlier chaos, filled with limpid woodwinds and luminous strings. “Mercury, the Winged Messenger” is a delicate scherzo whose tunes and phrases leap nimbly through the orchestra at a virtuosic pace. As the middle planet in the suite, “Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity” is the sentimental anchor of the work. Warm, lyrical, yet marked by English restraint, “Jupiter” itself is bisected by a stunningly beautiful chorale, the central theme of the movement, which was later extracted and assigned a patriotic text by Cecil Spring-Rice, “I Vow to Thee My Country.” “Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age” is a relentless and inevitable procession toward death, reworked from Holst’s own choral setting Dirge and Hymeneal. Holst noted that “‘Saturn’ brings not only physical decay, but also a vision of fulfillment.” Indeed, its coda comes with the peace of acceptance, in the spirit of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde. Playful and parodic, “Uranus, the Magician” is Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice on a grander scale. An ostentatious horn motif is reshaped into varied tangents, and the magician’s trickery seduces the ear until he abruptly disappears. “Neptune, the Mystic” is positively ethereal. There is no main theme per se, though bits of tunes surface and sink. A women’s chorus, heard for the first time, enters almost imperceptibly and remains after the orchestra dies away, growing, in the words of Holst’s daughter Imogen, “fainter and fainter in the distance, until the imagination [knows] no difference between sound and silence.”

Top honors. Herbert von Karajan’s 1961 The Planets with the Vienna Philharmonic (Decca) is powerful and majestic.

Spacey. Isao Tomita proves that masterworks can be bent to any manner of orchestration.

Superb playing and acoustics combine with a thoughtful, gripping interpretation to make Herbert von Karajan’s powerful 1961 rendition with the Vienna Philharmonic (Decca) the best of the more than seventy Planets recordings available at ArkivMusic.com. Bright brass in “Mars” go for the jugular in a chilling finale. A gentle “Venus” features sensuous strings brimming with rubato. A warm, virtuosic “Mercury” leads to a driving and buoyant “Jupiter.” The chorale within is lent appropriate majesty, but the movement never loses its humor or playfulness. “Saturn” features dark, ruddy playing from the strings and woodwinds in Karajan’s wistful, heartrending account. “Uranus” is given a razor’s edge by the Vienna brass, and the quick tempo of “Neptune” provides tension where one usually finds stasis.

Georg Solti’s 1979 set of Planets, with the London Philharmonic Orchestra (Decca), takes second place thanks to long, long orchestral lines, splendid interpretation and, most notably, sustained tension from the LPO throughout. Along with William Steinberg (below), Solti commands the finest “Jupiter” on disc. Well-pulsed and delightful, crystalline brass execute crisp runs with virtuosic technique. Solti nails the chorale, nobly gliding along. The lightness of this movement is remarkable, strong and assured, never lagging. “Mars” is rousing, sharp and animate, while “Venus” is expressive, if slightly harried. The LPO shapes “Mercury” with a nice Bartókian edge — gritty and folkish. “Saturn” is thoughtful and forward-moving, and Solti stretches the movement’s long progression to its limit before releasing to a benevolent denouement. He employs a similar schema in “Neptune” to fine effect.

Notable for the way it reveals inner voices and counterpoint, William Steinberg’s 1971 recording with the Boston Symphony Orchestra (Deutsche Grammophon) rounds out the top three, capturing Boston’s Symphony Hall in a spacious, bright ambience. At a lightning-paced six minutes and thirty-four seconds, “Mars” is exhilarating and unrelenting, with nice detail in the brass. “Venus” struts with sensuousness, but in the end returns to modesty. A Scandinavian lilt gives “Mercury” a bouncing rhythm to go with spot-on articulation. Brash and confident, “Jupiter” turns into a drunken ballad in its dance section and is deliberately paced, making for a fine contrast to the racing “Mars.” Steinberg pinpoints the nobility of the choral melody, which strides with humble determination.

Though simply dreadful from an audio standpoint, Holst’s own recording, with the London Symphony Orchestra circa 1922 (Pearl), is historically valuable for those interested in gaining insight into the composer’s vision of the work, which apparently included speedy tempos, notably in “Saturn” and “Neptune.” Be warned that it’s snap, crackle ’n’ pop all the way through, and that some instruments are at times muffled.

In the liner notes to the Mark Elder–conducted Hallé Orchestra premiere recording of The Planets with Colin Matthews’ added movement, “Pluto, the Renewer” (Hyperion), Matthews writes that he had “mixed feelings” when first approached about writing in the final planet. Unfortunately, Matthews didn’t succumb to his doubts and fears, and the result is a musically forgettable appendage that unbalances the suite. Making no attempt at pastiche, Matthews’ soundscape-scherzo races around en route to nowhere, occasionally recalling snatches of earlier movements. If you must own a “Pluto,” the preferred recording is that of David Lloyd-Jones and the Royal Scottish National Orchestra (Naxos). This generally good performance features a tight and foreboding “Mars” with imaginative tempos and a simply captivating “Mercury.” Lloyd-Jones’ “Saturn” reveals a fine progression from pain to acceptance. The sound is expansive, though unrelenting timpani throughout threaten at times to drown out everyone else in the orchestra and may cause subwoofer-replacement anxiety.

A fine endnote to Holst’s magnum opus on disc is the wonderfully entertaining and largely convincing 1976 The Planets by Japanese composer and synthesizer expert Isao Tomita (RCA), who performs his own electronic version of the work as a spaceship journey through the solar system. Apart from cuts in “Jupiter” and “Uranus,” and along with added sounds of rocket ships, deep space and mission control, the score is faithfully followed. Interestingly, the work begins as it ends, with the central theme of “Jupiter” warmly interpreted on a music box. That Tomita can even begin to evoke an emotional response with such farfetched orchestration speaks to his genius. That he achieves it speaks to Holst’s.

related...

-

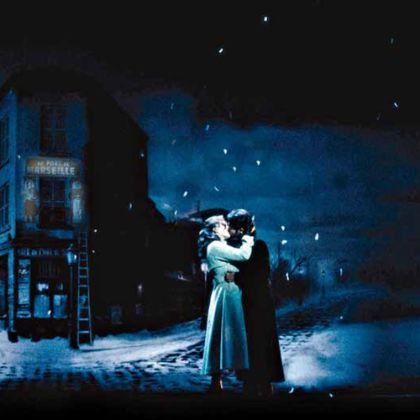

A Simple Love Story

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine -

When the Shoe Fits

Prokofiev’s Cinderella is much more than a charming retelling of the beloved fairy tale.

Read More

By Thomas May -

Celebrating Messiah

After 250 years, we still sing ‘Hallelujah’ for Handel.

Read More

By Ben Finane