The Art of Storytelling

Yo-Yo Ma speaks of artistic principles, Bach as universalist, deepening our perception and appreciation, liberal arts as continuous learning, and the unlimited creativity of nature.

By Ben Finane

Photographs by Jeremy Cowart

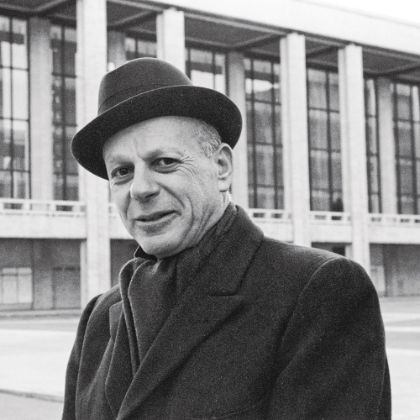

YO-YO MA IS America’s greatest living ambassador for classical music and the only cellist most people can recognize on sight. He is also the only interview subject of this magazine who has ever requested a résumé and bio from his interviewer. “Yo-Yo,” a Sony publicist told me, “likes to know who he is talking to.”

Ma has talked to and collaborated with a lot of people over the course of his musical journey, which in recent decades has led him away from traditional core-classical repertoire toward more worldly music, from Asia to Appalachia to Brazil and beyond. He is the artistic director of the Silk Road Project, which promotes the study of the cultural, artistic and intellectual traditions along the ancient Silk Road trade route that stretched from the Mediterranean Sea to the Pacific Ocean. He is a United Nations peace ambassador. In 2009 Sony Classical released a box set of over ninety CDs to commemorate Ma’s thirty years recording for the label. His latest album is a bluegrass collaboration with Stuart Duncan, Edgar Meyer and Chris Thile, The Goat Rodeo Sessions.

You have long been associated with the Bach Cello Suites — of course, so has the solo cello itself. But can you speak to what I would imagine to be a changing relationship over the years with the Suites?

I think that’s the nice thing — and I’m almost ashamed to say this — of knowing a set of works for fifty-one years [laughs]. In the way that I treasure old friendships, people I’ve known since grade school, it’s just great to know someone for that long. And it’s the same thing with Bach: some things are etched in your brain permanently from an early age — it’s literally the first piece of music I played. And of course a lot of people think, ‘Music: it’s notes written down and that’s it.’ Actually, that’s not it....

For people who re-read books, the second or third time, it’s always different! You see different things. The words haven’t changed, but you’ve changed, the environment’s changed. Therefore, your concept of the world has changed. Viewing that coded stuff [music as musical notes, i.e., sheet music], that changes, too. Which leads me to think a couple of things about Bach. Music is a non-material thing, but it is material in that when it’s alive, it’s energy through space. But when it’s coded [sheet music], it’s both a living and non-living material, the way that a virus — is it alive or is it dead? — gets activated at some point. So the code, to me, is actually something that can become living, and the code itself is what Bach put down that is translating something — living thoughts and ideas and concepts — into a musical kind of DNA. And I think it’s never something that is material and permanent or something that only changes as you change, but in fact it itself changes as we view it from a different perspective from the time and place where Bach translated ideas from. Does that make sense?

So therefore, the early exploration of Bach looking at patterns and perceiving what’s regular, what’s irregular — which is essentially the 0-1 of the digital age — [changes] to looking at it maybe in threes. Again, I’d like to try and deepen my own perception and appreciation of the music, working with people like Ton Koopman and talking to Christoph Wolffe, Mark Morris and Peter Sellars. They talked to me about the sociological implications of the movements, from old movements to the French-Italian to the more popular movements — Menuet — and the folk movements — Gigue — to the Sarabande, which has North African roots, then traveled to Spain and South America and up to France, where Bach picked up on it. I was exploring ‘What is the meaning of these notes?’ as if they were seeds that could live in other people’s minds. And if each seed lived in a creative person’s mind — or someone who is creative in a particular medium — and it lived with a long enough gestation period, how does each become born in a different way?

Does all of this translate into a quantifiable shift in how you approach these Suites?

Absolutely. It’s like your friend from grade school. It’s quantifiable in the sense that exploration with different intonations — in Baroque music, in fiddling, in Persian music — has given me a ton of appreciation for how to play minor keys, or rather, how many choices you have in terms of choosing intonation, bowings. Quantifiable? After playing bluegrass with Chris Thile, Edgar Meyer, Stuart Duncan — after watching the way Stuart improvises and does incredibly fancy bowing that gives a unique articulation, which Edgar also does — and applying it to Baroque music, that’s actually an aural visualization of performance tradition from way back when, before the era of recordings. So that, matched with Ton’s research, actually yields more perspectives on how different things are done and how they continue to live on in different generational permutations.

…

Mostly Ma. At ninety CDs, Yo-Yo Ma: 30 Years Outside the Box (Sony Classical) contains every original album the cellist has recorded.

…

So this leads me to wonder if and how the Silk Road Project has recontextualized classical music for you.

To me, any good musician of any era is taught a number of different values. First, you always want to make the music, uh... memorable. [Laughs.] Right? So in order for something to be memorable, you actually incorporate certain values in it. One is, the sound you make is a codification of something that is bigger than yourself. And it’s also something that brings people to the most, immediate, minute version of the moment. So you have to keep both things in mind at the same time: What’s the story? Where are you in the story?

In terms of our present era, we think of the world as one planet. And I think Bach thought of the world as the universe. He was a good Lutheran, but he didn’t confine himself by saying ‘I’m a Lutheran; I’m not interested in Catholic traditions.’ He was interested in Catholic traditions. He was interested in everything around him. Though he didn’t travel a lot, his imagination was everywhere.

“I think Bach thought of the world as the universe. He was a good Lutheran, but didn’t confine himself by saying ‘I’m a Lutheran; I’m not interested in Catholic traditions.’ ”

People around your age and my age don’t grow up, one, listening to one music; two, thinking they’re the most unique people on earth [laughs], that what they do is the most special. You have to find out who you are and how you fit in the general world. You and I and probably many of your readers have had a college education, probably a liberal arts education, and basically that’s what the liberal arts tell us: you learn continuously, constantly trying to find how to understand the people and the world around you. And one of the best ways to understand people is to understand what are the things that are deeply coded within them — their habits, what music they listen to, what foods they eat. And that’s the other artistic principle: the best way of learning these things is by going inside. It’s not cultural tourism — taking the bus, seeing the city and going back to the hotel — but it’s actually going inside someone’s home: you’re invited in, you interact on a personal level, one-on-one. And that’s when you’re taken in. And then you are bound by the rules of hospitality. I come visit your apartment, you take me in. These are your habits, and I don’t muck up your furniture. I don’t spit on your rug. I don’t break your bowls, and I say thank you. And if you come into my world, you’ll do the same thing. And to me that’s the basis of cultural interaction.

‘What’s your story? Where are you in the story?’ seems an excellent watchword for playing any piece of music.

Absolutely. As my wife reminds me all the time when I try to tell a joke — the first thing she says is ‘Don’t tell jokes because you’re not funny’ — anyway, the second thing is ‘You forgot the punch line again’ [laughs uncontrollably]. Or it’s like, ‘Don’t tell the shaggy dog story, because you’ve just lost your audience.’ So I keep in mind, based on my poor joke-telling record, that in performance one of the things that makes things magical is when you keep in mind the story, which is the content, and where you are in the story, which is how I’m communicating it technically. Am I focusing just on the technique? If I am, then you the listener will also focus on my technique: ‘Oh, look, he played this in tune — for the first time!’ [Laughs.] But part of the communication is you want to transcend technique. And what ultimately makes it memorable is that the thing that I care so much about lives inside somebody else’s head, and that it’s received, and they don’t dispose of it as soon as they hear it.

You have to keep that circle in mind all the time while you’re thinking about the content and communicating it: who is receiving it? Who are you? Why are you listening to this? Why would you care? Should you care? And if you do, what are you caring about? Are you the same as me? Are you different? How was your day? Does that impact the way you receive something? If you’re listening in your car, in the kitchen, in the shower — that becomes a sidebar to the conversation. You may be listening intently, you may be zoning out. Are you an active listener or a passive listener? Who are all the people listening and why? I think that that is an unbelievably important and probably less explored part of music and yet it is the element we need the most for the act of completion to take place.

Would you agree that any piece of music you learn helps you categorically with music you’ve already learned?

I think you’re always looking for building bricks of knowledge. Certain bricks you might chuck, but, on the other hand, there’s no brick that is not worthwhile to a certain point.

Worthy of consideration.

Exactly, because any material that might not be useful for one place might turn out to be incredibly useful in another place. With more experience, you’re hopefully more broad-minded in terms of finding the right place for it.

Ninety CDs. Looking over the enormity of this box and looking back on all these recordings, are there patterns or roads that, with the benefit of hindsight, reveal themselves?

I think curiosity is a hallmark. I’ve always been wondering about things. The kind of curiosity that leads to action is usually led by whatever situation I’m in, community or person — people that act as teachers or guides that take me into their world. My big passion is about people and about people-to-people contact. So, for example, moving from France to America. Different culture. What’s with all these things that are different? Buildings that are different, people talk different, speak different languages. And they say very different things, they make different assumptions. So I think that the curiosity about music is ‘Okay, I like this stuff, but who did it and why?’ You see a beautiful building. Who made that? Why was that built? Cars. Who thought of that? There was a world before cars. What was that like? Marlboro [Festival]. What’s that tradition about, and why do they not like Shostakovich? Suddenly you’re taken into a European tradition that could not incorporate a Soviet world. Not because they’re not interested, but because there was a cultural curtain. Or at Harvard, where it was ‘You do things well, physically, but you have no idea what you’re doing — you don’t know how to think.’ Or playing with Mark O’Connor and Edgar Meyer: ‘Well, you sound fine, but it really don’t sound that good to us.’ Why? Why not? In each world, it’s whom I encounter. A federal judge says, ‘I want you to talk about Albert Schweitzer because I’m doing a symposium on his life as a physician and as a great Bach scholar and as a theologian.’ And suddenly I have to think about what that means and why the Bach Suites are so long-lasting and why he did something impossible — by writing polyphonic music for a single-line instrument — and why it’s worth having impossible goals. How so much of the music of four billion people on earth — the people of the Silk Road — is about describing the universe, and how that’s a common goal of all music, whether in dance music or art music, and that that’s transcendence from reality and yet part of a reality. And how each person does it differently, and how we’re part of nature, and that nature has a greater imagination than any individual human can have, and how that relates to investigation in any field.

‘I’ve never in my mind put a lid on nature’s creativity. Humans put a lid on things. Nature has its own frame and I think of humans as part of nature.’

…

Round ’em up. A “goat rodeo” describes a situation in which a thousand things must go right in order for something to work. (l–r:) Chris Thile, Edgar Meyer, Yo-Yo Ma and Stuart Duncan

…

Sounds like a Frank Lloyd Wright approach.

Could be, and it’s also a Richard Feynman approach. Feynman said nature guards her secrets jealously, and we want to find out what her secrets are. That could describe Frank Lloyd Wright, Bach. That’s what we do.

We’re getting to seven billion people in the world now. And that sounds now like a discussable number, since we’re talking about a $14.3 trillion deficit. But I think to be able to encompass abstraction into concrete sounds and feel them, that’s the job of the musician. I can’t possibly connect to $14.3 trillion, but if I think about in what way can I start to feel the immensity of that, if I can do that in sound — and Messiaen can do it, right? So if you think about Messiaen and the thousands of rainbows that he talks about in one of the movements of Quartet for the End of Time —

— that he probably actually saw —

— yes, and not just because he had a detached retina. He really imagined them! And I would play that movement for children and say, ‘Who’s seen a rainbow?’ Well, a lot of people would raise their hands. But who’s seen a thousand rainbows? No one’s seen a thousand rainbows. Now here’s a piece of music that can conjure up a thousand rainbows.

Now, you’d say, ‘Messiaen? For children? Nah, forget it!’ No! It’s absolutely tactile, it becomes ‘Mommy, I saw a thousand rainbows!’ through hearing sounds. That’s transcendence, that’s something where you can actually bring abstraction to feeling, to something memorable.

So for The Goat Rodeo Sessions, I’m playing with a mandolin, an instrument that is an ancient instrument, that goes into the Silk Road, that goes to America, to Europe. And I feel I partake not just in the record-label category of ‘contemporary bluegrass.’ No! I’m talking to people: Edgar, who could have been a mathematician; Stuart, who could have been an engineer; Chris, Mr. Boy Wonder, who is excited by everything in the world. And we’re partaking in a deep human tradition of collaboration, where a single voice emerges from a group of four people and yet each voice maintains individuality at all times. Each voice tries to emulate other voices but also remains individual. That’s one of the deepest human things that has existed, and my God, that’s like a string quartet!

You’ve said in the past that we’re heading toward a ‘classical world music.’ Are there any drawbacks to a more open-source music?

I’ve never in my mind put a lid on nature’s creativity. Humans put a lid on things. Nature has its own frame and I think of humans as part of nature. So world classical music is actually humans dealing with humans in the natural world. Every single tradition that I know of is the result of successful creation. And world classical music already is: Philip Glass, Tōru Takemitsu, Tan Dun, Bartók, Steve Reich, Puccini. You look at how things are created, what the influences are, where they were hidden, where it’s actually publicly discussed, Rite of Spring. Talk about invention versus tradition: it’s both, and you don’t have to pretend anymore.

related...

-

Back to Bach

Pianist András Schiff revisits The Well-Tempered Clavier and other totems of J.S. Bach — on stage and on record.

Read More

By Bradley Bambarger -

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt