Why the ‘poor little dying girls’ hold no interest for mezzo-soprano Elīna Garanča

By Ben Finane

Born to a choral director father and a Lieder-singing mother, Elīna Garanča did not initially have her parents’ support to pursue a life of music. Yet her ascent through the opera world has been deliberate and inexorable. The Latvian mezzo-soprano made her American debut in 2008 at the Metropolitan Opera as Rosina in Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia. She is currently performing at the Met as Sesto in Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito.

There’s not much of an operatic tradition in Latvia, but there has long been a strong choral tradition that cuts through Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. Is there something special in the water of the Baltic Sea?

[Laughs.] I don’t think so. During the cold times, it really goes straight to the bones. Latvia as such is really anti-vocalist in that respect. When summer is over and the autumn rains begin, most of the singers get sick and it can take some strength to battle through the humid winters.

But I think it has something to do with the fact that Latvia has around two million folk songs and — as there are probably around two million Latvians in the world — it’s impressive to note that each of us could have at least one folk song.

The mezzo-soprano has had an evolving role in opera over the centuries and remains hard to pin down. How do you view the mezzo’s role today and its possibilities within the operatic world?

It probably depends on the repertoire you’re actually doing. Nineteenth-century French music is incredibly broad for a mezzo-soprano to be in the leading part. The mezzo-soprano is usually number three or four in the evening because you come after the soprano and tenor, who most of the time are taking the merits and credits of the opera because most of the important composers, particularly in Italian music, have written the leading parts for soprano and tenor. And probably, somehow, the diva and the tenor singing — and hitting — the high Cs might be more exciting sometimes. However, for mezzo-soprano, the variety of roles we can do, in my opinion, is much wider. The sopranos soon get stamped — the ‘poor little dying girls’: all these Lucias, even the Toscas, they all end up dying, and from the beginning of the opera you know how it’s gonna end. And mezzos, in that respect, are witches, bitches and nasty women. Jealousy is just much more interesting. Particularly, if you are a lyric mezzo-soprano, you can even start with the boys’ parts, and that gives you — within a twenty-five-year career — a very wide spectrum of characters that you can play.

Singers, vocal soloists, are different from other soloists because they ‘evolve’ into different roles, which affects their instrument in a way that solo pianists or violinists don’t have to worry about. If I’m a pianist I can play Beethoven, then Ravel, then back to Bach, et cetera without harming my ‘instrument.’ But — if you’ll permit me a sports metaphor — being a singer is a lot like being a boxer. Move up in weight class (as a boxer) and you lose some speed. Train on the speed bag and you lose some power. Taking on Verdi, for example, could make you lose some top range. Sing a lot of coloratura and you may lose some power below. As a mezzo, when you decide to move from one role to the next, what considerations must you take into account?

I think it’s rather like athletics and sprints. There are people who just have the stamina to run marathons and there are people who are incredible at running the hundred-meter. It’s been proven that their muscle complexions are slightly different. For the singers, it’s the same with vocal chords and their stamina: the length and thickness of your vocal chords strongly determines the type of voice you are. You can, of course, work on the technique, making the voice more agile, controlling your breathing and being able to sustain longer phrases and build up the register. But there are limits set by nature, and again I think the mezzo-soprano has these possibilities of stretching yourself a little bit more. As I said, you start with the boys’ roles, with the Handel, with the Baroque and Mozart and then eventually, if you have the capacity and haven’t really abused yourself, you can end up with Wagner and Verdi later on.

Bel canto really is ‘beautiful singing’ — being able to develop the phrase, control the voice with quite little and very simple orchestral accompaniment, and the beauty of the singing vocal line that just floats, so to say, above the orchestra.

Is that the road map for the path you hope to take?

I hope so, yes, because I think that my voice can take it. And I realize and notice that Mozart was wonderful for a certain time, and also bel canto, Rossini in particular — but it was not really my cup of tea. I knew how to do coloratura, but it was not a natural thing for my voice. To people who say ‘Every singer should start with Mozart,’ there is a lot of truth to that, but not all voices can really do Mozart because the vocal chords’ structure and physical build of the body is for something else. I actually apply singing different music much more to the style of how you should be approaching it. My voice is my voice and I should be able to sing more veristic roles or more Baroque roles according to the style that’s required, be it more legato or be it more instrumental, starting the tone with less vibrato or not making the voice vibrate at all. There are plenty of singers who have said, ‘I don’t sing with my voice, I sing with the technique and with musical knowledge.’

What makes Mozart a great starting point for many singers?

I think it’s control of your machinery, so to say. Mozart writes very, very instrumental for the voice. And very often the orchestration — in comparison to Puccini or Wagner or Strauss — is very pure and simple. And you have a very plain phrase with instrumental jumps from one tone to the other and you can’t slide and you can’t hide behind screaming emotions and long portamentos, so you need to get the tone pure and get on top of the tone in any register. And have a certain agility in making the coloraturas, as in, for mezzo-soprano, La clemenza di Tito or Idomeneo. And, for sopranos, Donna Anna [in Don Giovanni] and Fiordiligi [Così fan tutte].

Your Bel Canto album [(Deutsche Grammophon)] takes the term at its most specific definition: the arias of Bellini, Donizetti and Rossini. Tell me what this tradition means to you.

It really is ‘beautiful singing’ — being able to develop the phrase, control the voice with quite little and very simple orchestral accompaniment, and the beauty of the singing vocal line that just floats, so to say, above the orchestra. And in that CD you can hear that very often the orchestra is really a very simple and repetitive construction of chords and arpeggios, and you, with your voice, have to create a beautiful — very simple, in appearance — melody, with floating canons, with crescendos, decrescendos, and very often without changing too many consonants: it’s all on a long vowel, long simple legato phrases, which is very difficult.

Can a bel canto tradition ever clash with developing character — let’s say a role that could require you to make ugly sounds?

On the contrary! It’s much easier to be ugly and provide an ugly sound. The only thing is if you know how to make an ugly sound without harming yourself. Everybody knows how to scream. But you have to know how to scream correctly so you’re not finishing the performance with bleeding vocal chords or being left without voice the next morning. So the technical capacity of knowing how to do Mozart and bel canto actually gives you a fantastic base to later on start to abuse your voice, let’s say, quite naturally once you start to sing more dramatic or more verismo roles, as the emotions can sometimes overwhelm you at that very situation.

When you go from a ‘darker’ role such as Charlotte [in Massenet’s Werther] to singing [Bizet’s] Carmen, is there a period of retraining or ‘lightening’ of the voice?

Well, it definitely changes with experience that you gather through the years, however I still am not a fan of mixing two completely different roles. When I make my calendar I like to see a very low curve — of either moving up or down in register. I would not agree to do Carmen and then two weeks later to do a Mozart because I think it would be just too much of a change in elevation — say from floor ten to floor one hundred twenty-five. With time, you know how fast and when to switch the voice. But in my own experience doing certain roles, I need a certain warm-up and it requires more concentration during the rehearsal period, particularly if you come from more dramatic repertoire suddenly into bel canto. And I use these rehearsal periods to sing every day and get back into shape, and if I know that something isn’t working then I go to see my teacher.

What has been your most challenging role?

Each role is somehow challenging. So far, it was probably [Rossini’s] Cenerentola because I’ve never considered myself a coloratura singer, so for me to get all those notes right — low, middle and high — was really a marathon with the quality of a sprint, where you really have to be at a hundred-meters-per-ten-seconds pace permanently for forty-two kilometers. Coming from that repertoire, obviously Carmen was a great challenge because if people are used to seeing you in boys’ roles or more bel canto-ish roles, suddenly to be on new ground with Carmen is also challenging, just to prove that lyric mezzo-sopranos can do these kinds of roles — and be dark and fatal enough in the way you express or translate roles. In [Richard Strauss’s] Rosenkavalier, obviously Octavian is a very demanding role because it’s so long and you’re basically onstage from beginning to end and with many provocations to fulfill. Sometimes after singing more dramatic repertoire, you return to bel canto and think, ‘Oh my God, how am I going to hit that high B-flat?’ because it suddenly seems to be at stratospheric heights. I think it’s true what my older colleagues always say: each role is a new challenge; it’s a new function of muscles until you have this role in the throat.

The press release for your new album, Romantique [Deutsche Grammophon], notes: ‘Keen to avoid adding any of the heavier mezzo roles to her repertory, Garanča instead chose to concentrate on romantic character studies.’ Does that speak to a long-term strategy?

Eventually, of course, I want to add heavier roles. The danger is — with the theaters — that as soon as you add one of the more dramatic roles to your repertoire, all the theaters automatically want you to sing only that role. This creates a snowball, and people offer you more and more heavy roles. For example, if I agree now to do Eboli [in Verdi’s Don Carlos] I can guarantee you that within the next two or three years I would be offered only Eboli in every theater. And then very soon afterwards it would be Brangäne [in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde] or Amneris [in Verdi’s Aida]. That kind of pressure I want to avoid. We do plan all of our calendars several years ahead and even if I note that my voice is starting slowly to change, I still want to fulfill my contracts — for example, Bellini’s I Capuleti e i Montecchi I’m taking in 2016. So I’m trying to keep my voice a little bit fresher and not to ‘dramatize’ myself too soon. It’s true that my dream is to some day sing Amneris, however I don’t give myself a set point and say, ‘Okay, when I’m forty I want to do this role and when I’m forty-three, I want to do another role.’ I am maybe sometimes a bit careful, maybe I don’t challenge myself too much, but as they say: ‘Better to be careful than to be sorry.’

That’s not the first time I’ve heard you say that Amneris from Aida is one of your dream roles. What is it that draws you to that role and to that opera?

I think this role just has everything. She’s a very strong and powerful woman and very weak to the strongest feeling in the world — which is love. With her desperation and her being in love, if she gets offended she just becomes a wild animal. So to show all these character differences within the opera is very, very exciting and I just love the music. And the last act — I think it’s just a masterpiece.

It’s interesting that the character you just painted there —

[Starts laughing.]

— some of that seems to occur within the role of Carmen as well.

I knew that was coming. [Laughs.]

I imagine though that even with the role of Carmen, the vocal demands remain greater than those of the acting.

I think that holds for all these kind of roles. Very often you can hide behind the acting, and you do hide very often behind the acting because the voice maybe is not ready for the role, or one is especially tired that night — but that’s also more interesting for the public, which is generally unaware of the depth of technique behind the singing. Nowadays we don’t just sing anymore, we also act, but I’ve always said I’m a singer, not a dramatic actress, so for me the challenge and the more quantifying, satisfying thing is to know myself that I have had a good sung performance. If the acting comes to it too, that’s great. But it’s important for me that I also hide behind certain things. As far as Carmen compared to Amneris, Carmen is more difficult because everybody ‘knows’ how the Carmen should be and people are so different about sexuality and sensuality — and what’s sexy for someone may not be sexy for someone else.

They have it that a blonde woman with blue eyes can't really play Carmen.... Everybody thinks the south of Spain is filled only with black-eyed and black-haired women.’

They have preconceived ideas about Carmen that they don’t bring to Aida.

Yeah, they have it that a blonde woman with blue eyes can’t really play Carmen. Most of them can’t really explain why, just that it’s so unnatural; everybody thinks the south of Spain is filled only with black-eyed and black-haired women.

Of course you had a tremendous brunette wig that you pulled off for that production.

Tremendous indeed! [Laughs.]

You’ve expressed a desire to one day do some Broadway. Are the worlds of opera and Broadway and theater now coming closer together?

In a way, obviously through the cinema and hype, but particularly in the approach, in the media approach — in America mostly, you can feel it — maybe yes. However, now being in that world and talking to people who have done Broadway and opera, or stage directors working with both, I don’t think that Broadway would be something for me, for the reason that I just cannot imagine myself for half a year doing eight shows a week — it’s not so much the vocal challenge but the mental challenge. And I have a problem where I need to review everything I do on the stage, and it’s only human that after doing fifteen shows in two weeks that somehow you get into a routine. That’s absolutely normal and I don’t think you can reproach the people who are doing this, however I don’t think I could really be happy in that.

I think the fascination that I have with musicals is that there are very, very few stage directors — and singers — who are really devoted to trying the maximum within opera. I’m contradicting myself here, saying that I’m an opera singer and I concentrate on singing, however I do try and push myself to limits to really be able not only to sing but to speak and dance and really be flexible on the stage. This is a liberty that musical-theater people have of singing, talking and dancing, and very strongly choreographed pieces — which is missing in opera. Also, of course, we do not have mics to push our voices. Opera singing needs a completely different support; it’s easier to sing to a house of four thousand with mics than two thousand with no mics.

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine -

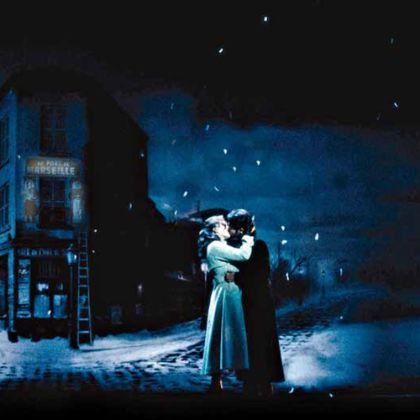

A Simple Love Story

It’s no accident that Puccini’s La bohème remains the most performed opera.

Read More

By Robert Levine