Off the Page, Against the Grain

It’s the rare performer who improvises in classical music.

By Bradley Bambarger

Like most things in our society over the past century, classical music has become characterized by a division of labor. From before Bach to Beethoven, composers were also performers; as the Romantic age turned into the modern era, roles hardened into separate specialties: creators (composers) and re-creators (performers). Much was gained:

Composers wrote evermore complex scores that performers realized with increasing perfection. Yet something was lost: the art of improvisation, of musicians freely creating, and risking, in the moment. With that loss has gone a sense of spontaneity that thrills artist and audience alike.

“If Mozart could hear people perform his music today,” surmises pianist and Harvard professor Robert Levin, “he would be amazed at our accuracy, but he would be annoyed at the premium placed on accuracy over expression.”

Miles Davis said that there is no such thing as a “wrong” note; the note that’s played next determines whether it’s good or bad. Of course, this improvisational mindset — the ability to think, even feel, on your feet — is the essence of jazz (a similar attitude, if not fluency, informs folk music and even some rock and pop genres). But it’s mostly a foreign concept for conservatory grads bred to learn and transmit exactly what a composer put on the page — nothing less, nothing more.

“What we gain in technical perfection, we can lose in a sense of play and adventure,” says Levin, who made a name improvising his own cadenzas to Mozart’s concertos, something the composer would have expected of any eighteenth-century pro. “Much of the classical music world is based on competitions, spliced recordings and concert promoters who want a slick product. Nothing much goes wrong in this world, but nothing goes terribly right, either. If people say classical music is dying, well, maybe that’s one of the reasons.”

Of course, interpretive subtleties can be heard in today’s classical concert halls, though individuality is often limited to the play-even-slower-when-it-says-slow variety. Nineteenth century–trained piano virtuosos such as Josef Hofmann and Wilhelm Backhaus even improvised preludes to the Chopin or Schumann they played in concert, a warm-up/scene-setting practice called “preluding.” Thought exciting at the time, such invention became frowned upon as the modern age of recording cast interpretations in amber and cultural mores shifted in favor of letter over spirit.

An inspiration for later generations when it comes to improvising in the concert hall has been American composer–pianist Frederic Rzewski, seventy-two. Extolling Rzewski as a paradigm are pianists as different as Marc-André Hamelin (renowned for realizing the most transcendentally complex classical scores) and Ethan Iverson (formerly of alt-jazz trio The Bad Plus, which incorporates everything from Nirvana to Ligeti in its twenty-first-century vision). Many of Rzewski’s compositions call for improvisation, and he performed in group improvisations for decades as a member of Musica Elettronica Viva. Rzewski has even improvised within such totems as Beethoven’s “Appassionata” Sonata, a practice that might have made even Hofmann blanch.

Improvisers with the stature of Rzewski are like white tigers in the classical realm. But there are some venturesome talents out there, on mainstream stages and in new-music circles. Pianist Gabriela Montero — a protégé of Martha Argerich — has made her reputation by giving improvisation equal time with interpretation. Cameron Carpenter carries on the tradition of free improv in the organ world, with his own glam-pop spin. Violinist Carla Kihlstedt, thirty-eight, and multi-instrumentalist/composer Fred Frith, sixty-one, are collaborators from different generations and represent a rare breed that writes, improvises, plays and sings in music from avant-folk to art rock to contemporary composition. Perhaps it’s these musicians Mozart would recognize as kindred spirits.

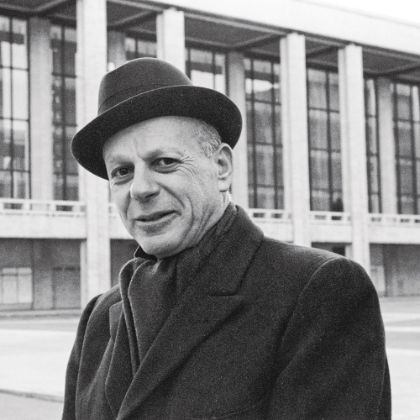

Robert Levin

Gabriela Montero

Speaking A Language

Although we know Bach, Mozart and Beethoven through their compositions, they were perhaps most celebrated in their day for their improvisations. Mozart spontaneously wove variations on hit opera arias at his performances, like a jazzman would on a popular song.

“Mozart was the Duke Ellington of the eighteenth century, just as it was Duke Ellington who was the Mozart of the twentieth,” Levin says. “Mozart was just speaking the dialect from 1780s Vienna, and Ellington was speaking one from 1930s Harlem. But the aesthetic goals are similar, with enormous freedom within a stylized structure. The chord changes of the jazz player are the figured bass of the eighteenth century.”

To make Mozart feel contemporary, composers from Brahms to Schnittke have composed cadenzas in their own styles for his concertos. Levin finds these interesting, but they aren’t for him: “A truly idiomatic performance of an eighteenth-century concerto involves improvisation. After all, a cadenza — meant to be an electrifying display of virtuosity by the soloist — should feel dangerous, like the performer is walking a tightrope and the audience lets out a sigh of relief at the end: ‘Whew, he made it.’ ”

Improvising in any music demands a musician be steeped in that genre’s particular vocabulary. The sixty-two-year-old Levin — who recorded a milestone series of the Mozart concertos with improvised cadenzas (and a period-instrument orchestra, for Decca) — is one of the great students of Classical-era language, using as a model the cadenzas Mozart wrote out for others and the period treatises that codified the lingua franca of the day.

Pianist Keith Jarrett — one of today’s iconic jazz improvisers, whether with his Standards Trio or in extemporaneous solo marathons — is one of the few jazz players to cross over into high-end classical performance, having recorded repertoire from Bach and Mozart to Shostakovich and Lou Harrison. Ironically, though, Jarrett doesn’t improvise the cadenzas in Mozart concertos, feeling that he doesn’t have the essential mastery of that Classical-era language.

The pitfalls are deep if a musician doesn’t know the vocabulary, whether it’s a classical musician trying to play jazz or the other way around. Ethan Iverson notes: “Thinking you can improvise jazz without understanding the folklore of the music will result in a horror story. If the style is abstract and non-traditional, pulling off an improvisation is more likely. However, when [our trio] The Bad Plus plays twentieth-century classical music by Ligeti, Stravinsky and Babbitt, Reid [Anderson] and I don’t improvise much at the bass or piano: We have too much respect for the composer’s harmonic language to think we can just jump in and sound right in the style. Dave [King] improvises the most, at the drums.”

Levin has been called upon to improvise in such twentieth-century music as Edison Denisov’s Oda for clarinet, percussion and piano — in which, at a certain point in the score, the Russian composer dropped standard musical notation for geometrical shapes. Levin says, “How do you play a rectangle, triangle and square? He was basically saying, ‘Wing it.’ He wanted to elicit the unexpected. Later, though, he wrote all that out; evidently, he wasn’t persuaded by the creative qualities of his performers.”

Levin laments the practice of “teachers drumming risk-taking out of students.” But there are classical survivors he admires, particularly British organist-pianist Wayne Marshall, who has unusual improv fluency in both the classical organ tradition and a vintage jazz-pop style.

Then there is Venezuelan-born American resident Gabriela Montero, forty, who has recorded three discs’ worth of spontaneous fantasias on Baroque and Romantic repertoire (EMI). Moreover, she reserves the second half of her live recitals for improvising on themes suggested by the audience — a crowd-pleasing trick that also kick-started Levin’s improvising career twenty-three years ago.

“Unlike me, Gabriela isn’t a stylistic purist — she will take a Mozart tune and turn it into salsa, a tango or whatever,” Levin says. “More power to her.”

A Personal Connection

Montero says that one teacher she had for ten years disapproved, admonishing her thusly: “Improvisation has no worth; don’t embarrass yourself with it.”

It was this sort of stifling that caused Montero to quit music several times. She says, “I was born to be a pianist, but I wasn’t fully engaged in music until into my thirties. I even thought at one point of dropping music to become a psychologist. It was finally giving rein to my improvising that allowed me to truly live music.”

Devoting the second half of her recitals to improvisations on themes from the audience has proved a big hit. She says, “People sing out everything from ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb’ and football anthems to a theme from The Rite of Spring or a Beatles song. Or they play me ringtones. I find that people love it more than anything else. It becomes a personal, interactive thing with listeners, and audiences today want that sort of connection.”

Montero never studied composition or much theory, and says her improvisations “have nothing to do with thinking. I don’t guide it. I allow myself to be taken.”

When Montero plays a Beethoven sonata or one of Rachmaninoff’s Etudes-Tableaux, she plays it “one hundred percent by the book,” she adds. “But I think improvising can actually heighten a performer’s sense of empathy, so that when you play Beethoven and Rachmaninoff, you feel closer to their intentions.”

Marc-André Hamelin shares Montero’s appreciation for improvisation, although he is a very different sort of pianist. Only forty-eight, Hamelin’s vast Hyperion discography is already one of the treasure troves of recorded history. It includes great Haydn, Chopin and Liszt, but is especially valuable for peerless takes on rarities by Godowsky, Medtner and such obscure keyboard mystics as Alkan and Sorabji. Carrying on the composer-pianist tradition, Hamelin has also written a set of piano etudes. But he only improvises in private. “I don’t improvise in public because I don’t have the experience it takes to be good at it,” Hamelin says. “But I believe improvising, even in private, is a wonderful way to commune with one’s instrument and get in touch with your creativity.”

Although celebrated for his ability to play seemingly unplayable scores, Hamelin shares Levin’s disenchantment with the fact that “schools tend to cultivate the athleticizing of performance over fostering invention.” Moreover, he adds, “the obsession with the text can put a stranglehold on the ability of a musician to feel free.”

Feeling Free, in Church

From the young Bach’s heroes to Bruckner and beyond, the most enduring traditions of improvisation in classical music have originated with church organists. The French Romantic organ school has been passed down in cathedrals from Widor, Vierne and Dupré to Messiaen, Langlais and Naji Hakim. It is ironic that the ostensibly strict and circumscribed environment of the church kept free improv alive, but, Levin explains, “because organ music was always based around church services, it had to be flexible; the organist had to be able to wing it if the bishop spilled the wine or the bride lost her shoe.”

Very much in his own way, twenty-nine-year-old organist Cameron Carpenter is carrying the torch for this legacy, in both churches and concert halls, on vintage pipe organs and digital instruments. Few can argue that Carpenter, trained by Paul Jacobs at Juilliard, has technique and intellectual power to burn. But some find his yen for glittery outfits and camp flamboyance disturbingly Liberace-like, even if his showman’s flair is drawing listeners beyond the decidedly hermetic organ realm.

The Pennsylvania native admires improvisers, from florid jazz titan Art Tatum (“huge virtuosity and rhythmic sophistication”) to French organist-composer Jean Guillou (“a genius for giving personal performances”). Carpenter’s own improvisational ambitions are multifarious: there is his more traditional organ improv, in which he improvises an encore to a Bach recital based on thematic and harmonic touchstones from the previous hour; he also regularly improvises live soundtracks to such classic silent films as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, drawing on a bank of previously developed leitmotifs and textural combinations. Next, he is planning to experiment with long-form, raga-like improvisations.

Improvising helps a musician see music not as an engraved absolute, but as something more natural, “allowing for spontaneous creativity,” Carpenter says. “Being able to improvise a fugue demands serious contemplation and practice. Improvisation takes people who also don’t give a damn what people think, the ones who aren’t worried about what will happen if they play a wrong note and it winds up on YouTube.”

Experience in improvising is invaluable for shortening response time in contrapuntal situations or enabling quick recovery from a finger-slip, Carpenter points out. Advantages also accrue to spontaneous musicians when it comes to pleasing an audience; echoing Montero, he says he finds that listeners tend to react most strongly to the music that comes from him, in the moment: “Perhaps it’s an influence from pop, but there is more of an expectation of a personal statement in music today.”

Relationships, Not Genres

In contemporary composition, improvisation as an ideal has come in and out of vogue. Such disparate post-war avant-gardists as Cage, Lutoslawski, Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez experimented with various “aleatoric” processes that gave performers a degree of freedom. In the late fifties, the Gunther Schuller–led Third Stream movement tried to meld jazz improvisation and classical form. Today, figures from composer-pianist Rzewski to composer-guitarist Steve Mackey incorporate improvisation into their work.

Fred Frith is another. Classically trained on violin as a boy in England, he switched to guitar after hearing the Shadows and the Beatles. He co-founded art-rock band Henry Cow in the late sixties, made influential albums of solo improvisation on prepared guitars in the seventies and became a fixture of the downtown New York experimental scene in the eighties. Frith has played in various groups since, including the song-oriented Cosa Brava with Carla Kihlstedt and harpist Zeena Parkins. In recent years he has also composed works for such top new-music groups as the Arditti Quartet, Asko Ensemble and Ensemble Modern.

Writing music for Ensemble Modern that incorporated improvisation was a frustrating experience, Frith says: “Ensemble Modern can read and play anything. A few of the players had a feel for improvising, but most didn’t like it — it freaked them out. So the first piece I wrote for them, Traffic Continues, was pretty unsatisfying, even though they were brave enough to go out on a limb with me. Traffic Continues II: Gusto, was better, because I brought in some outside players that can really improvise. My ideal twenty-first century musician is a player who can read, improvise, play rock, anything.

“Improvising demands mastery,” adds Frith. “But it’s a paradox: You have to be in control, but you have to let go. That tension is what can make it special.”

Frith, who teaches composition and improvisation at Mills College in Oakland, senses “a generational loosening” among classical musicians. He cites such young groups as So Percussion, the Eclipse Quartet and Calder Quartet for their “fearlessness.” He says, “It’s a taste thing with younger players — they enjoy and respect improvising. . . . It’s also pragmatism; they realize one has to be more versatile to be a working musician these days. But I find that since the sixties, the hierarchy in music — with strict classical playing on top and everything else below — has imploded, on the street if not in the institutions.”

As one of Frith’s “ideal twenty-first-century musicians,” Carla Kihlstedt’s manifold pursuits stem from the way she “thinks in terms of relationships, not genres.” The violinist-singer has pursued instrumental cinematics with Tin Hat, avant-folk with Two Foot Yard and theatrical art rock with Sleepytime Gorilla Museum, as well as sessions for the likes of Tom Waits and singing and playing simultaneously in such bespoke compositions as Lisa Bielawa’s Kafka Songs.

Bielawa also wrote her Double Violin Concerto for Kihlstedt and Colin Jacobsen, who premiered it with the Boston Modern Orchestra Project in 2008. To ensure an air of unpredictability from performance to performance, the composer included a cadenza of structured improvisation. Kihlstedt explains: “Lisa wrote a beginning gesture and a way out, but left the middle for us to improvise using an ornament library she created. Lisa was very hands-off about the length. That kind of trust from composer to performer is rare, and it allowed us to enter the music in a deeper way.”

When it comes to improvising, the challenge is “to hold yourself to a rigorous standard in structure and storytelling,” Kihlstedt says. “If you’re not telling a story, then you’re just throwing notes at people.”

Improvising has changed the way she practices, the violinist adds: “I don’t practice just a single way of doing something. I practice making decisions. It gives me more choices even when I play fully notated music. I’m better able to go where the music leads me in any given moment, technically and emotionally.”

related...

-

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Back to Bach

Pianist András Schiff revisits The Well-Tempered Clavier and other totems of J.S. Bach — on stage and on record.

Read More

By Bradley Bambarger