A Father’s Lament

Finding solace in the sound of authentic sorrow

By Rev. Jake Bohstedt Morrill

For the twenty-five years that she had been alive, she had wanted a motorcycle. No one was surprised. She was one who wanted the wind in her hair, the speed of the highway up close. To bend into the turns. So, after she got married to a quiet soldier stationed in Korea, she herself moved to Colorado to be in the mountains. And this is where, at long last, she got the motorcycle she’d wanted. It was all that she had imagined it could be. Her voice on the phone — to her husband in Korea, to her parents in Tennessee — had a thrill to it. Even more joy than was her usual custom. Her enthusiasm bubbled over. Made you want to ride a motorcycle yourself. Made you see life’s previously unimagined edges and heights.

Then, late one night, at her parents’ house, the phone call. A state trooper. Somber tones. Something had happened. Nothing that they could do. There were decisions to be made. For instance, where to ship the casket, and would someone come meet it. It took a while to reach the young husband in Korea. On the phone, the arrangements took a while. So many details. Decisions. And it was barely morning time in Tennessee. After some coffee, things started to develop. The funeral home would handle things. A relative could go out to Colorado, to accompany the body back home. And they called the church to see if the minister could put together a service.

They weren’t church people themselves. They were a military family; that was their tribe in any of the countless places they’d lived. Yes, you bowed your head if someone was praying, out of respect. But church on a regular basis just wasn’t their thing.

I remember them all filing into my office. The mother, lips pursed. The young husband, jet-lagged from the travel between Korea and East Tennessee, disoriented by this even stranger new terrain without the one who was his joy. Last of all, reluctantly, warily, the father. A large man, the bushy mustache and stout, muscled build you see in retired military. He filled up a chair, shoulders down, and he looked at the floor, silent. You got the sense that he might have been more comfortable standing guard at the door. When the mother said what a joy their daughter had been to her husband, he did not move a muscle. Did not make a sound.

The mother did all the talking. She had a few written notes. This is where the story of her daughter came pouring out, and her lips trembled with joy and some mirth to remember the rash, sprightly child that had somehow ended up in their sober, orderly household. The mirth, of course, was dashed with sorrow. But this was her duty, this was the mother’s duty: to make sure I knew who her daughter was. Or had been. There was the usual confusion of verb tenses between present and past, so typical of fresh grief, when what makes sense is disordered.

Did the young husband have anything to say? Anything important to share? He brightened in remembrance and then was baffled, shaking his head incredulously. Said she had always talked about the Tao Te Ching. Would quote from it. Wanted him to read it. And he had meant to. But that wasn’t his kind of thing. He thought if he had read it, he might have been able to understand her a little more. He had always meant to. But the Army kept you so busy. He hadn’t gotten around to it. There was a copy on my shelf, and I handed it to him. He held it, turned it over in his hands.

Then, it seemed, nothing more could be said.

The service was a couple of days later. The funeral home was packed with young people, dressed in suits and nice dresses, unsure and a little shocked, unpracticed at what to do in this situation. A little nervous laughter rang here and there. But mostly there was a hush.

This was fairly early in my ministry, so the voice I used had a sonorous and stentorian tone, substituting some make-believe authority for the gravity I feared I lacked. Because, really, what did I know? What could I say? My life, to that point, had been spared that kind of violence of the heart. Perhaps what everyone needed, after days of phone calls and arrangements, of condolences and flowers, was what happened late in the service, at the end of the prayer. There was a moment of silence. And it was there, in that silence, I heard it.

There are singers who tell you that the sound of human sorrow — of loneliness and despair — sounds like a moaning train. And we have heard the rumble of devastation in footage from tsunamis or avalanches — sound so immense and so vast that it becomes almost physical in its force. But at the funeral home, what rose up from that silence was neither machine nor mountain. It was the sound of an animal whose heart had been torn out. A deep, choking sob. Then, a howl of anguish. It was the raw protest of life in the face of the abyss. This sound filled the room, and at first, I could not tell from what direction it came.

Then I saw, in the first row, where the family was seated, those massive shoulders, bound up in a dark suit. The whole body. The red face, shining with tears. They say that a person who is crying has turned into a puddle, but the father — so impassive before, so stoic, a veritable rock — had become the dark, swirling ocean. His pain rose and cascaded. Then choked off, and fell silent. And, once again, all was still.

The Forty-Second Psalm begins as follows:

As the hart panteth after the water brooks,

so panteth my soul after thee, O God.

My soul thirsteth for God, for the living God:

When shall I come and appear before God?

My tears have been my meat day and night, While

they continually say unto me, Where is thy God?

When I remember these things, I pour out my soul

in me: For I had gone with the multitude, I went

with them to the house of God, With the voice of

joy and praise, with a multitude that kept holyday.

Why art thou cast down, O my soul? and why art

thou disquieted in me?. . . .

In the popular imagination, the Bible exists as a kind of cookbook for moral behavior. But what rarely is mentioned is that the texts contained in the books of the Bible are the furthest thing from straightforward moral instruction. Instead, they are rambling, rollicking stories of screw-ups and doubters and an unfolding character named God who is dimly apprehended and most often misunderstood. There is dissonance and disagreement. It is like a patchwork quilt, joined together unevenly so that the seams are showing. This is rough work. Very human.

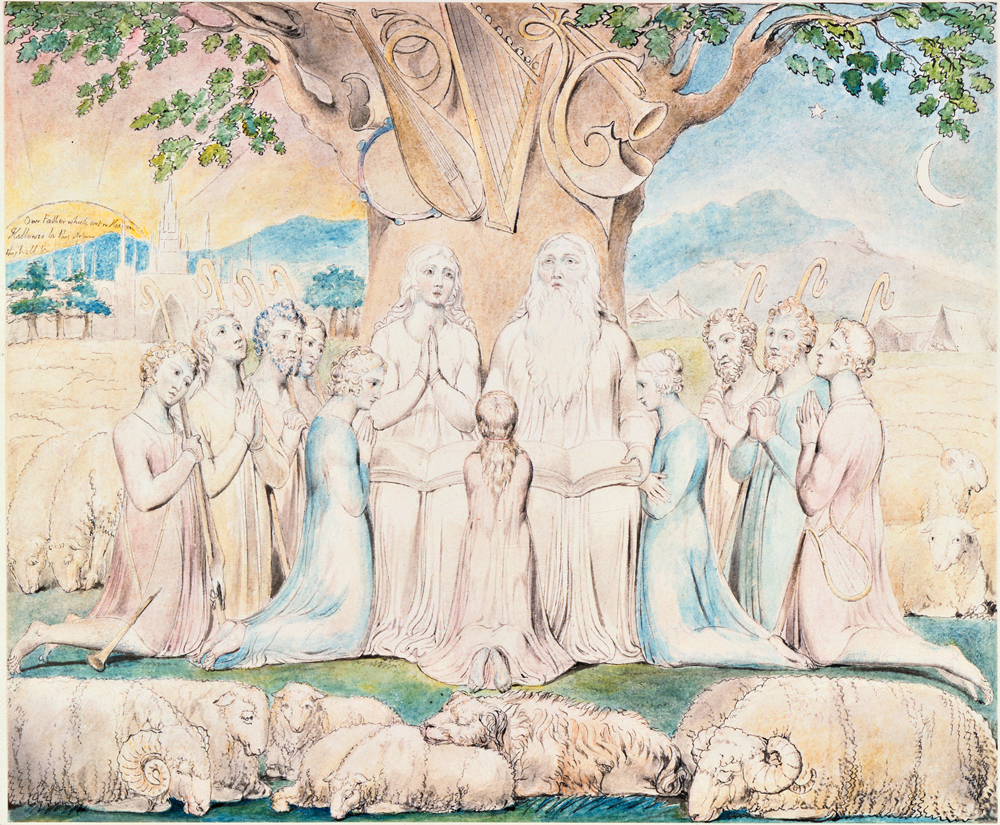

The word psalm means “music sung to a harp or lyre,” and some of the either 150 or 151 psalms in the Old Testament include musical instruction, hinting at their longtime use as congregational hymns. Tradition ascribes authorship of the psalms to King David, but in fact they emerged from the misty recesses of tradition, from sources unknown, from the collective imagination of a people who knew joy and discovery, but who journeyed forth through the ages harboring intimate sorrow and loss, ragged suffering and heartbreak.

Yes, there are psalms of celebration, of praise. But the largest mood that prevails is stark lamentation. It is not the voice of cynicism or reckless abandon, but of those who have known heartbreak. Who are struggling to hold on. To believe. To start over.

We tend to look to religion for something solid to lean on. And yet we also know — and are reminded in the story of Job, another heartbreaking story in the Old Testament — that well-wishers and advice-givers and hand-wringers and maudlin mourners are not much help in times of grief. When life has laid us low, instead of pat answers, instead of glib platitudes, more often the right medicine is the voice of someone who has been there. Of someone whose suffering — and whose struggle to claim hope — might just echo our own. In this voice, in this presence, we discern not something to lean on, but someone to walk with. Someone who won’t hush up our pain, or briskly wipe clean our tears.

This is the sound we hear in the music of lamentation. Think of Ariadne’s heartrending “Lasciatemi morire,” the only piece of music to survive from Monteverdi’s L’Arianna. Think of Purcell’s Dido singing “When I am laid in earth.” Or Giordani’s “Caro mio ben.” Call back the chill of hearing it. The sense of being, at long last, unmasked.

In this age of irony, there is the impulse to cut short these expressions, to hide them away. We fear the abyss, and perhaps the abyss within us most of all. But when we find ourselves in the valley of the shadow of death, without any certainty about how we’ll go on, and with pain that grips and squeezes and crushes the heart, claims to “self-reliance” fall apart, blow away. In those times, as our elders would have it, we stand in need. Not of cheering up: no. Nor advice. Nor even, I’d say, the calm of perspective. What we need in those times is to hear, from some unknown source, the low moan of humanity, the cry of dismay, and the stubborn reassurance that this one life really matters. To say, without silky eloquence, simply this: that it matters, this struggle. This sorrow. This love we have known. It matters that we once had joy and that the joy is no more. And at those moments, in that valley, may we have close at hand, if not a companion or confidant, something very much like it. May we have the Book of Psalms. Or Carissimi’s Jephte. Or Purcell’s “Dido’s Lament.” If we do, we may take solace in this unshakable fact: even cast into darkness, with our heart splitting open, none of us is alone.

Rev. Jake Bohstedt Morrill is a Unitarian Universalist minister in East Tennessee.

Photos: The Pierpont Morgan Library/Art Resource, NY

-

From Christemasse to Carole

The birth of Christmas in medieval England

Read More

By David Vernier -

The Next (Not-So-)Big Thing

New chamber orchestras are popping up all over America.

Read More

By Colin Eatock