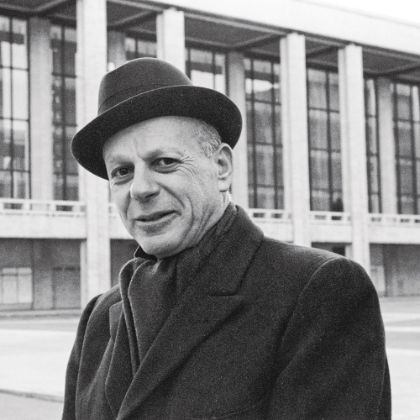

(1927–2015)

An unlikely unifier

By Jens F. Laurson

Kurt Masur passed away at the age of eighty-eight. He was born in Lower Silesia, and moved to Leipzig to study conducting after World War II — into which he was drafted at seventeen. It was in Leipzig where he rose to musical fame as the Kapellmeister of the Gewandhaus Orchestra in 1970. He ceased using a baton after he barely survived a car crash in 1972, in which his first wife died.

With almost a thousand concerts given abroad, Masur was a cultural ambassador for the German Democratic Republic and also one of its more important foreign currency cash cows. He was at best politically disinterested and certainly outwardly loyal to the regime that permitted him a privileged life within the GDR. Optimistic commentators suggest that he simply used his influence with the party to get money — and then a new concert hall for his orchestra. Then General Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party Erich Honecker obliged and, although the country could not afford it, had the third (still superb) concert hall which opened in 1981 in time for the two hundredth anniversary of the orchestra moving to the original Gewandhaus.

In Leipzig, Masur hurtled toward fame beyond his musical acclaim with his call for prudence during anti-government demonstrations on October 9, 1989, further promulgated through leaflets and a short speech broadcast on radio. His moral authority was attested to have helped keep the gatherings, which eventually led to the fall of the GDR’s regime, peaceful. Suddenly, Masur found himself the conductor of German unification. The New York Times stylized him a “cousin of Martin Luther”; locals wanted him nominated for the Nobel Peace prize; and politicians approached him to stand for the (largely representational) role of German President. He opted instead to become the music director of the New York Philharmonic.

The New York Philharmonic wasn’t in good shape after neither Pierre Boulez nor Zubin Mehta was able to counter the slump into which the orchestra had fallen after its Bernstein high. There was a fear that “Leipzig-on-the-Hudson could be a duller town than Mehtaville” (Donal Henahan). But while Masur might not have made the New York Philharmonic an interesting orchestra, he certainly made them better.

In 2000, Masur was asked to steer the London Philharmonic Orchestra while they looked, without hurry, for a new conductor. (It turned out to be very successful Vladimir Jurowski.) In 2002, Masur became the music director of the Orchestre National de France, a post which he held until 2008 (to be succeeded by Daniele Gatti).

Masur’s conversion from regime-benefactor to regime critic and hero of peaceful regime change, meanwhile, was a late one. The ascent to hero-of-the-free-people did not sit well with everyone who knew him from the years before. An attempt to solicit feedback from players at the Gewandhaus Orchestra who had worked under the late maestro was met with a unified refusal to comment — a non-statement as telling as any statement could have been.

Kurt Masur was huge, towering over his orchestra at six foot five, but with soft gestures, which made for an intriguing contrast — as it did to his sometimes brusque demeanor towards orchestra members. The tower started to slope and droop with age. The left hand became limp and just twitched along with the music. The right hand would eventually be jittery, and long before Kurt Masur publicly admitted in October of 2012 to be suffering from Parkinson’s disease, which would betray him and his music making. In the end, there was a sense of his being trotted around the concert circuit despite diminishing musical returns, which was sad. But he could still draw crowds, and musicians who knew him suggested that music was the only thing that kept him going. Masur himself said: “What should I do? Just quit conducting and wait for death?” Masur instead continued until shortly before his death, including a documented concerto at the Aurora Festival in Trollhättan, Sweden, where he conducted Wagner. It is hard not to be moved by the humanity that emits from the players as they perform for their frail maestro leading from his wheelchair.

related...

-

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Back to Bach

Pianist András Schiff revisits The Well-Tempered Clavier and other totems of J.S. Bach — on stage and on record.

Read More

By Bradley Bambarger -

Evolution of Form

Everything you always wanted to know about Baroque concertos (but were afraid to ask)

Read More

By David Hurwitz