A jazz master’s music seeks out the universal.

By Clifford S. Tinder

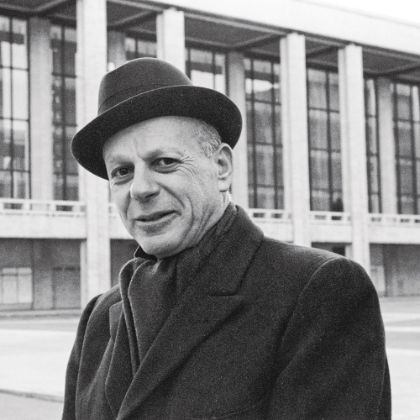

Ornette Coleman (1930–2015), passed away five years after the publication of this feature. —Ed.

“Next time I’m playing in New York, you can bring your horn and sit in — any time. I’ll be disappointed if I see you without your horn.”

What! Did I just hear Ornette Coleman invite me to play with his band at their next New York club date?

For someone who fell under the spell of Coleman’s incredible, emotional musical expression as a fourth grader listening to his seminal recording The Shape of Jazz to Come, it’s like having God invite you to Sunday brunch in heaven.

Ultimately, this inclusiveness is what Coleman is all about, and sheds light on his often misunderstood theory of Harmolodics. For Ornette, Harmolodics places harmony, melody, tempo, rhythm and phrasing into equal positions in the creation of music. The theory moves music away from pre-determined tonal centers, rigid rhythmic constructs and traditional European concepts of harmonic structure. It’s a peek into the open group expression of Sound Grammar, the CD that won Coleman the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for Music.

“All I’ve ever wanted to do is to express something that everybody can enjoy. It’s amazing that a person, whether they can read or write, can play something that will put tears in your eyes. We should realize that every day, because it only makes living with humans more enjoyable.”

It’s exactly this democratic worldview that enables Coleman to cross the boundaries of style and genre with such natural ease. He is equally comfortable writing the symphonic work Skies of America; accepting a commission from the Kronos Quartet; scoring the ballet Architecture in Motion; performing with Yoko Ono, the Grateful Dead, or Pat Matheny; recording with the tribal musicians of Joujouka, Morocco; and forming Prime Time with two electric bassists, two electric guitarists and two drummers to perform music that melds free jazz, funk and R&B with Coleman playing alto saxophone, trumpet and violin.

“What I want to hear in music are two of the most powerful aspects of the human condition: ‘I love you’ and ‘I forgive you.’”

“For some reason, the quality of music all over the world still has the same root name for the sound — the sound is the same in all music. An emotion is represented by how it sounds. That’s the one thing that I have been trying to get more free of every day — to allow any person that speaks any language to communicate with sound grammar,” Coleman says with his quiet North Texas inflection. “Whether someone is Chinese, Greek or Spanish, the emotion part is still human. There is no human being that is left out. Every human being has to express something that has to do with their origin, but what they are as human beings is the same.

“I’ve always left my mind and heart open to support anybody. Since I have been doing that, I have been running into many different qualities of melodies that represent the same results. I don’t know how many languages there are in the world, but the notes carry the messages of all those languages. I know that I have learned a lot by staying open to that. When I play with someone from a different culture, even though we don’t speak the same language, once you play together, you find out that those same notes in another language haven’t changed sound.”

After solidifying his sound and the personnel of his working band in Los Angeles during the 1950s, Coleman arrived on the New York scene in November of 1959 for a legendary stint at the Five Spot. The piano was noticeably absent from the band in order to loosen the constraints of chord changes and allow more room for evolving tonal centers. Drummer Billy Higgins and bassist Charlie Haden were set free from the traditional role of the rhythm section while trumpeter Don Cherry and Coleman delivered a constant creative dialogue, unrestricted by many of the “rules” of jazz. The New York artistic world was thrown into an intelligentsia meltdown. Coleman’s critics thought he was a charlatan who couldn’t play in tune, while supporters maintained he was changing the shape of jazz to come. Leonard Bernstein and Virgil Thompson hailed him as a genius and true innovator, going as far as to help him secure a Guggenheim Foundation composition grant.

“You know what people call sharp and flat, or unison and harmony — they are describing an emotion. It’s so true and real that it’s going to catch on one day.”

What Coleman was really doing was shaping each note, using intonation and changing tonal character to express profound feeling. In other words, he was doing exactly what the blues and R&B players did with the music that surrounded him growing up in Fort Worth. “There were a lot of places that featured blues players. When I started playing free jazz, I just made it a part of the way that I performed — and it worked.”

In 1960 Coleman released Free Jazz, a thirty-seven-minute collective improvisation for a double quartet consisting of Coleman (alto sax), trumpeter Don Cherry, bassist Scott LaFarro and drummer Billy Higgins on one stereo channel and Eric Dolphy (bass clarinet), trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Ed Blackwell on the other channel, with cover art by Jackson Pollock. It changed jazz forever and gave the burgeoning avant-garde movement its name. With no strict structure or repeated themes, the musicians were improvising freely, bringing their individual sound and playing style to amazingly successful musical expressions that grew like crystals from their own internal logic and beauty.

Coleman’s current working band still includes two bass players. “The bass changes the sound of whatever tonic you are in. And that’s good because it means that you can be in the key or out of the key. At least that’s what it does for me. I would rather have a bass section than a piano. With two basses, one is for the key and the other is for the modulation. Which is really good.

“I’m working on a new composition with strings. But this time, I’m working it so that all the musicians that are playing with me will be equally valuable for each other. I’m not playing it directly for myself. I would like the musicians to express their selves as freely as I would.”

If the haunting 1972 recording Skies of America is any foreshadowing, this new work could blossom into another genre-busting milestone in a career littered with iconoclastic firsts. Skies, Coleman’s twenty-one-movement symphonic suite, was recorded by the London Philharmonic and later performed in 1997 by Kurt Masur, the New York Philharmonic and his electric band Prime Time.

“Instead of worrying about the key, the musicians need to find out how many keys you can play in without worrying about the tone. Find something to play that everybody will say, ‘Wait a minute, show me what that was.’ The one thing that exists in knowledge is education. Education in music is a sound, but it has a name, and you know what? Nobody knows the name. Sound doesn’t have a tonic. You get your tonic from the quality of how you use sound,” Coleman says with a chuckle.

“There are three changes: C major seventh, E-flat minor seventh and D minor seventh with a flatted fifth. If you take those three changes and express them on whatever instrument you play, it frees you up. The emotions of playing free will be understood by all people. The emotions will communicate more directly to them than your trying to figure out what changes and key to play in. Can you imagine... when you have sex, you don’t have to count. That’s the way music should be.”

This explanation of the three-chord progression really baffled me for a few days. Wasn’t Coleman trying to break loose of the shackles of chord changes? Then I sat down at the piano and played the chords — and the realization came. These three chords are part of what jazz musicians call a “turnaround,” a transitional progression used to return to the tonic of the tune. But Coleman’s turnaround never resolves; there is no clear tonal center suggested, freeing you to go anywhere and, as Coleman does, everywhere. In September Coleman and his band opened the Jazz at Lincoln Center 2009–2010 season, something that seemed impossible only five years ago.

“What I want to hear in music are two of the most powerful aspects of the human condition: ‘I love you’ and ‘I forgive you.’ You know how you find a girlfriend and fall in love, it is the same feeling with music. And that’s good, it’s really good.”

Whether he is expressing himself with his uniquely colorful fashions, or playing alto, violin and trumpet like no one else on this planet, or composing music that brilliantly defies classification, it all comes back to his need for the purest, most honest, human expression — Ornette Coleman’s gift to human beings.

Photos: Getty Images, Jan Persson

related...

-

Master Builder

His compatriots made institutions of their music. William Schuman made institutions.

Read More

By Russell Platt -

Respighi: Beyond Rome

Respighi’s set of variations is cast away for his more

Read More

‘Roman’ repertoire.

By David Hurwitz -

L’amico Fritz

Mascagni delivers beautiful music, libretto be damned.

Read More

By Robert Levine